The Scream

| The Scream | |

|---|---|

| Norwegian: Skrik, German: Der Schrei der Natur | |

| |

| Artist | Edvard Munch |

| Year | 1893 |

| Type | Oil, tempera, pastel and crayon on cardboard |

| Movement | Proto-Expressionism |

| Dimensions | 91 cm × 73.5 cm (36 in × 28.9 in) |

| Location | National Museum and Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway |

The Scream is a composition created by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch in 1893. The Norwegian name of the piece is Skrik (Scream), and the German title under which it was first exhibited is Der Schrei der Natur (The Scream of Nature). The agonized face in the painting has become one of the most iconic images in art, seen as symbolizing the anxiety of the human condition. Munch's work, including The Scream, had a formative influence on the Expressionist movement.[1]

Munch recalled that he had been out for a walk at sunset when suddenly the setting sun's light turned the clouds "a blood red". He sensed an "infinite scream passing through nature". Scholars have located the spot to a fjord overlooking Oslo[2] and have suggested other explanations for the unnaturally orange sky, ranging from the effects of a volcanic eruption to a psychological reaction by Munch to his sister's commitment at a nearby lunatic asylum.

Munch created two versions in paint and two in pastels, as well as a lithograph stone from which several prints survive. Both painted versions have been stolen, but since recovered. In 2012, one of the pastel versions commanded the highest nominal price paid for an artwork at a public auction at that time.

Sources of inspiration

[edit]

In his diary in an entry headed "Nice 22 January 1892", Munch wrote:

One evening I was walking along a path, the city was on one side and the fjord below. I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord – the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The color shrieked. This became The Scream.[3]

He later described his inspiration for the image:

I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.[3][4]

Some scholars believe, based upon these accounts, that Munch was describing a terrifying emotional experience that would today be called a panic attack.[5][6][7][8]

Among theories advanced to account for the reddish sky in the background is the artist's memory of the effects of the powerful volcanic eruption of Krakatoa, which deeply tinted sunset skies red in parts of the Western hemisphere for months during 1883 and 1884, about a decade before Munch painted The Scream.[9] This explanation has been disputed by scholars, who note that Munch was an expressive painter and was not primarily interested in literal renderings of what he had seen. Another explanation for the red skies is that they are due to the appearance of nacreous clouds which occur at the latitude of Norway and which look remarkably similar to the skies depicted in The Scream.[10][11] Alternatively, it has been suggested that the proximity of both a slaughterhouse and a lunatic asylum to the site depicted in the painting may have offered some inspiration.[12] The scene was identified as being the view from a road overlooking Oslo, by the Oslofjord and Hovedøya, from the hill of Ekeberg.[13] At the time of painting the work, Munch's manic depressive sister Laura Catherine was a patient at the mental asylum at the foot of Ekeberg.[14]

In 1978, the Munch scholar Robert Rosenblum suggested that the strange, skeletal creature in the foreground of the painting was inspired by a Peruvian mummy, which Munch could have seen at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris.[15] This mummy, which was buried in a fetal position with its hands alongside its face, also struck the imagination of Paul Gauguin: it stood as a model for figures in more than twenty of Gauguin's paintings, among those the central figure in his painting Human misery (Grape harvest at Arles) and for the old woman at the left in his 1897 painting Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?.[16] In 2004, Italian anthropologist Piero Mannucci speculated that Munch might have seen a mummy in Florence's Museum of Natural History which bears an even more striking resemblance to the painting.[17] However, later studies have disputed that theory, as Munch did not visit Florence until after painting The Scream.[18]

The imagery of The Scream has been compared to that which an individual suffering from depersonalization disorder experiences, a feeling of distortion of the environment and one's self.[19]

Arthur Lubow has described The Scream as "an icon of modern art, a Mona Lisa for our time."[20] It has been widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of modern humanity.[1]

Versions

[edit]

Munch created four versions, two in paint and two in pastels. The first version was painted in 1893, between Berlin in Germany and Åsgårdstrand in Norway.[21] It was exhibited the same year, alongside other artworks in a series which Munch called The Frieze of Life.[22][23] It is in the collection of the National Museum of Norway in Oslo. This is the version that has the barely visible pencil inscription "Kan kun være malet af en gal Mand!" ("could only have been painted by a madman"). A pastel version from that year, which may have been a preliminary study, is in the collection of the Munch Museum, also in Oslo. The second pastel version, from 1895, was sold for $119,922,600 at Sotheby's Impressionist and Modern Art auction on 2 May 2012 to financier Leon Black.[24][25] The second painted version dates from 1910, during a period when Munch revisited some of his prior compositions.[26] It is also in the collection of the Munch Museum. These versions have seldom traveled, though the 1895 pastel was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from October 2012 to April 2013,[27][28] and the 1893 pastel was exhibited at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2015.[29]

Additionally, Munch created a lithograph stone of the composition in 1895 from which several prints produced by Munch survive.[30] Only approximately four dozen prints were made before the original stone was resurfaced by the printer in Munch's absence.[31]

The material composition of the 1893 painted version was examined in 2010.[32] The pigment analysis revealed the use of cadmium yellow, vermilion, ultramarine and viridian, among other pigments in use in the 19th century.[33]

Pencil inscription

[edit]

The version held by the National Museum of Norway has a pencil inscription, in small lettering, in the upper left corner, saying "Kan kun være malet af en gal Mand!" ("could only have been painted by a madman"). It can only be seen on close examination of the painting. This had been presumed to be a comment by a critic or a visitor to an exhibition. It was first noticed when the painting was exhibited in Copenhagen in 1904, eleven years after this version was painted. Following infrared photography, the study of the handwriting now shows that the comment was added by Munch.[34] The theory has been put forward that Munch added the inscription after the critical comments made when the painting was first exhibited in Norway in October 1895. There is good evidence that Munch was deeply hurt by that criticism, being sensitive to the mental illness that was prevalent in his family.[35]

Thefts

[edit]The Scream has been the target of several thefts and theft attempts. Some damage has been suffered in these thefts.

1994 theft

[edit]On 12 February 1994, the same day as the opening of the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer,[36] two men broke into the National Gallery, Oslo, and stole its version of The Scream, leaving a note reading "Thanks for the poor security".[37][38] The painting had been moved down to a second-story gallery[39] as part of the Olympic festivities.[40] After the gallery refused to pay a ransom demand of US$1 million in March 1994, Norwegian police set up a sting operation with assistance from the British police (SO10) and the Getty Museum and the painting was recovered undamaged on 7 May 1994.[39] In January 1996, four men were convicted in connection with the theft, including Pål Enger, who had been convicted of stealing Munch's Love and Pain in 1988.[41] They were released on appeal on legal grounds: the British agents involved in the sting operation had entered Norway under false identities.[42]

2004 theft

[edit]The 1910 version of The Scream was stolen on 22 August 2004, during daylight hours, when masked gunmen entered the Munch Museum in Oslo and stole it and Munch's Madonna.[43] A bystander photographed the robbers as they escaped to their car with the artwork. On 8 April 2005, Norwegian police arrested a suspect in connection with the theft, but the paintings remained missing and it was rumored that they had been burned by the thieves to destroy evidence.[44][45] On 1 June 2005, with four suspects already in custody in connection with the crime, the city government of Oslo offered a reward of 2 million Norwegian krone (roughly US$313,500 or €231,200) for information that could help locate the paintings.[46] Although the paintings remained missing, six men went on trial in early 2006, variously charged with either helping to plan or participating in the robbery. Three of the men were convicted and sentenced to between four and eight years in prison in May 2006, and two of the convicted, Bjørn Hoen and Petter Tharaldsen, were also ordered to pay compensation of 750 million kroner (roughly US$117.6 million or €86.7 million) to the City of Oslo.[47] The Munch Museum was closed for ten months for a security overhaul.[48]

On 31 August 2006, Norwegian police announced that a police operation had recovered both The Scream and Madonna, but did not reveal detailed circumstances of the recovery. The paintings were said to be in a better-than-expected condition. "We are 100 percent certain they are the originals," police chief Iver Stensrud told a news conference. "The damage was much less than feared."[49][50] Munch Museum director Ingebjørg Ydstie confirmed the condition of the paintings, saying it was much better than expected and that the damage could be repaired.[51] The Scream had moisture damage on the lower left corner, while Madonna suffered several tears on the right side of the painting as well as two holes in Madonna's arm.[52] Before repairs and restoration began, the paintings were put on public display by the Munch Museum beginning 27 September 2006. During the five-day exhibition, 5,500 people viewed the damaged paintings.[53] The conserved works went back on display on 23 May 2008, when the exhibition "Scream and Madonna – Revisited" at the Munch Museum in Oslo displayed the paintings together.[54]

In 2008 Idemitsu Petroleum Norge AS committed an endowment of 4 million Norwegian krone towards the conservation, research and presentation of The Scream and Madonna.[55]

Record sale at auction

[edit]The 1895 pastel-on-board version of the work, owned by Norwegian businessman Petter Olsen, sold at Sotheby's in London for a record price of nearly US$120 million at auction on 2 May 2012.[56][57] The bidding started at $40 million and lasted for over 12 minutes when American businessman Leon Black by phone gave the final offer of US$119,922,500, including the buyer's premium.[25] Sotheby's described the work as "the most colorful and vibrant" of the four versions Munch painted, noting also his hand-colouring of the frame on which he inscribed his poem which detailed the picture's inspiration.[27] After the sale, Sotheby's auctioneer Tobias Meyer said the work was "worth every penny", adding: "It is one of the great icons of art in the world and whoever bought it should be congratulated."[58]

The auction was contested by the heirs of Hugo Simon,[59] who sold it to Norwegian ship owner Thomas Olsen, Petter's father, "around 1937".[60][61][62][63]

The previous record for the most expensive work of art sold at auction had been held by Picasso's Nude, Green Leaves and Bust, which went for US$106.5 million at Christie's two years prior on 4 May 2010.[64] As of 2018, the pastel remains the fourth highest nominal price paid for a painting at auction.[65] The work had a presale estimate of $80 million, the biggest presale estimate ever set by Sotheby's.[66]

In popular culture

[edit]In Philip K. Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the main character and his partner, Phil Resch, view the painting in an art gallery. Resch comments that the painting reminds him of how he imagines androids feel.[67]

In the late twentieth century, The Scream was imitated, parodied, and (following the expiration of its copyright) outright copied, which led to it acquiring an iconic status in popular culture. It was used on the cover of some editions of Arthur Janov's 1970 book The Primal Scream.[68]

In 1983–1984, pop artist Andy Warhol made a series of silk screen prints copying works by Munch, including The Scream. His stated intention was to desacralize the painting by making it into a mass-reproducible object. Munch had already begun that process, however, by making a lithograph of the work for reproduction. Erró's ironic and irreverent treatment of Munch's masterpiece in his acrylic paintings The Second Scream (1967) and Ding Dong (1979) is considered a characteristic of post-modern art.[69] The expression of Kevin McCallister (Macaulay Culkin) in the poster for the 1990 film Home Alone was inspired by The Scream.[70][71]

The Ghostface mask worn by the primary antagonists of the Scream series of horror movies is based on the painting. It was created by Brigitte Sleiertin of the Fun World costume company for the Halloween market, before being discovered by Marianne Maddalena and Wes Craven for the film.[72]

The principal alien antagonists depicted in the 2011 BBC series of Doctor Who, named "The Silence", have an appearance partially based on The Scream.[73]

In 2013, The Scream was one of four paintings that the Norwegian postal service chose for a series of stamps marking the 150th anniversary of Edvard Munch's birth.[74] In 2018 Norwegian comedy duo Ylvis made a musical based on the painting's theft starring Pål Enger who stole it in 1994.[75]

A patient resource group for trigeminal neuralgia (which has been described as the most painful condition in existence) have also adopted the image as a symbol of the condition.[76]

In most renderings, the emoji U+1F631 😱 FACE SCREAMING IN FEAR is made to resemble the subject of the painting.[77]

A simplified version of the subject of the painting is one of the pictographs that was considered by the US Department of Energy for use as a non-language-specific symbol of danger to warn future human civilizations of the presence of radioactive waste.[78]

The cover art for the 2018 MGMT album Little Dark Age shows a figure resembling the subject of the painting, albeit in clown-like makeup.[79]

Gallery

[edit]-

1893, pastel on cardboard. As possibly the earliest execution of The Scream, this appears to be the version in which Munch mapped out the essentials of the composition.

-

1893, oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard. The first version publicly displayed, and perhaps the most recognizable is located at the National Museum of Norway in Oslo.

-

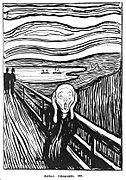

1895, lithograph print. About 45 prints were made before the printer re-used the lithograph stone. A few were hand-coloured by Munch.

-

1895, pastel on cardboard. It was sold for nearly US$120 million at Sotheby's in 2012 and is in the private collection of Leon Black.

-

1910, tempera on cardboard. This version was stolen from the Munch Museum in 2004 but recovered in 2006.

-

Undated, ink drawing. This composition, which features the central figure from The Scream is in the collection of the University Museum of Bergen.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Eggum, Arne (1984). Munch, Edvard (ed.). Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies. New York, NY: C.N. Potter. p. 10. ISBN 0-517-55617-0. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ (59°54′02.4″N 10°46′12.9″E / 59.900667°N 10.770250°E)

- ^ a b Stanska, Zuzanna (12 December 2016). "The Mysterious Road From Edvard Munch's The Scream". Daily Art Magazine. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Aspden, Peter (20 April 2012). "So, what does 'The Scream' mean?". Financial Times. ProQuest 1008665027.

- ^ "The Scream (painting by Edvard Munch) | Description & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 September 2024.

- ^ "Why Munch matters in the modern age of anxiety". Brummell. 9 April 2019.

- ^ Hoummos, Basima Abu Al (8 August 2018). "Munch's The Scream - artmejo".

- ^ "How Edvard Munch grappled with existential dread". faroutmagazine.co.uk. 22 August 2024.

- ^ Olson, Donald W.; Russell L. Doescher; Marilynn S. Olson (May 2005). "The Blood-Red Sky of the Scream". APS News. 13 (5). American Physical Society. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Svein Fikke (2017). "Screaming Clouds". Weather. 72 (5): 115–121. Bibcode:2017Wthr...72..115F. doi:10.1002/wea.2786. S2CID 125733901.

- ^ Prata, Fred; Robock, Alan; Hamblyn, Richard (1 July 2018). "The Sky in Edvard Munch's The Scream". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 99 (7). American Meteorological Society: 1377–1390. Bibcode:2018BAMS...99.1377P. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0144.1.

- ^ Fineman, Mia (22 November 2005). "Existential Superstar: Another look at Edvard Munch's The Scream". Slate. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Egan, Bob. "'The Scream' (various media 1893–1910) – Edvard Munch – Painting Location: Oslo, Norway". PopSpots. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- ^ Rajvanshi, Khyati (12 June 2022). "Behind the Art: Why Edvard Munch's 'The Scream' is considered as an icon of modern art". The Indian Express. Indian Express Limited. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Rosenblum, Robert (1978). "Introduction". Edvard Munch: Symbols & Images (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. p. 8. ISBN 3925402969.

- ^ Ziemendorff, Stefan (10 July 2014). "La momia de un sarcófago de la cultura Chachapoyas en la obra de Paul Gauguin" [A mummy from a sarcophagus of the Chachapoyas culture in the works of Paul Gauguin]. Cátedra Villarreal. 1 (2): 229–243. doi:10.24039/cv20142240. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Lorenz, Rossella (7 September 2004). "Italian Mummy Source of 'Scream'?". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 11 October 2004. Retrieved 12 December 2006. (waybacked mirror).

- ^ Ziemendorff, Stefan (9 July 2015). "Edvard Munch y la Momia de un sarcófago de la Cultura Chachapoyas" [Edvard Munch and the mummy from a sarcophagus from the Chachapoyas Cultur]. Cátedra Villarreal. 1 (2): 214–225. doi:10.24039/cv20153257. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Simeon, Daphne; Abugel, Jeffrey (2006). Feeling Unreal: Depersonalization Disorder and the Loss of the Self. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 0-19-517022-9.

- ^ Lubow, Arthur (March 2006). "Edvard Munch: Beyond The Scream". Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "The Scream (Edvard Munch, 1893)". Artchive. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "The Scream, 1893 by Edvard Munch". www.edvardmunch.org.

- ^ "10 things you may not know about The Scream". The British Museum.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (2 May 2012). "'The Scream' Is Auctioned for a Record $119.9 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b Crow, Kelly (11 July 2012). "Munch's 'The Scream' Sold to Financier Leon Black". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 August 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ Ydstie, Ingebjørg (2008). "Introduction". The Scream. Munch Museum. p. 10. ISBN 978-82-419-0532-2.

...has since been generally dated 1893. This date has been intensely disputed since the 1970s, however, based on the consensus in the professional field, the Munch Museum has now decided to correct its official standpoint, and presumes that 1910 is a more probable date of origin.

- ^ a b Carol Vogel (17 September 2012). "'Scream' to Go on View at MoMA". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Edvard Munch: The Scream". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Jonathan Jones (23 September 2015). "Side by side, Edvard Munch and Vincent van Gogh scream the birth of expressionism". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "The Scream". Becoming Edvard Munch – Influence, Anxiety, and Myth. Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Alan Parker (2 May 2012). "Will The Real Scream Please Stand Up". Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Brian Singer, Trond Aslaksby, Biljana Topalova-Casadiego and Eva Storevik Tveit, Investigation of Materials Used by Edvard Munch, Studies in Conservation 55, 2010, pp. 1–19. Available also on issuu.com

- ^ Edvard Munch, 'The Scream', ColourLex

- ^ Siegal, Nina (21 February 2021). "Art Mystery Solved: Who Wrote on Edvard Munch's 'The Scream'?". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Hågård Gustavsen, Alv. "Could only have been painted by a madman". National Museum of Norway. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Iqbal, Nosheen; Jonze, Tim (22 January 2020). "In pictures: The greatest art heists in history". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "4 Norwegians Guilty In Theft of 'The Scream'". The New York Times. AP. 18 January 1996. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Alex Bello: From the archive, 9 May 1994: Edvard Munch's stolen Scream recovered in undercover sting The Guardian, 9 May 2012

- ^ a b Dolnick, Edward (2005). The Rescue Artist: A True Story of Art, Thieves, and the Hunt for a Missing Masterpiece. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-053117-1.

- ^ "On this day: Art thieves snatch Scream". BBC News Online. 12 February 1994. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- ^ "Master plan". The Guardian. 13 June 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ^ Hart, Matthew (2004). The Irish Game: A True Story of Crime and Art. Viking Canada. p. 184.

- ^ "Scream stolen from Norway museum". BBC News. 22 August 2004. Retrieved 3 September 2006.

- ^ "Oslo police arrest Scream suspect". BBC News. 8 April 2005. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Famous Munch paintings destroyed?". Norway Post. 28 April 2005. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Reward offered for Scream return". BBC News. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Three guilty of The Scream theft". BBC News. 2 May 2006. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Entertainment | Scream theft museum reopens doors". BBC News. 18 June 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Munch paintings recovered". Aftenposten. 31 August 2006. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Stolen Munch paintings found safe". BBC News. 31 August 2006. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Munch paintings 'can be repaired'". BBC News. 1 September 2006. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Museum to exhibit damaged Munch paintings". Aftenposten. 12 October 2006. Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Fans flock to Munch Museum to see damaged Scream, Madonna". CBC News. 2 October 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Munch Museum". Munch.museum.no. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Ødegaard, Torger (2008). "Foreword". The Scream. Munch Museum. ISBN 978-82-419-0532-2.

- ^ "'The Scream' Is Auctioned for a Record $119.9 Million". The New York Times. 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Top 10 Most Expensive Painting Ever Sold". NewsFlashing.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Edvard Munch's iconic artwork The Scream sold for $120m". BBC News. BBC. 3 May 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Noce, Vincent. "Le 'Cri' de Munch à la criée". Libération (in French). Retrieved 17 April 2021.

Ce Cri appartenait aux descendants d'un richissime armateur norvégien, Petter Olsen, qui l'avait acheté au galeriste Hugo Simon en 1937.

- ^ Finkel, Yori (2 May 2012). "Edvard Munch's 'The Scream' goes for $119.9 million at Sotheby's". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

The first owner of the work sold at Sotheby's was German chicory and coffee mogul Arthur von Franquet, a patron who also owned Munch's 1892 painting "Girl by the Window," now at the Art Institute of Chicago. Its second owner was the Berlin banker and art collector Hugo Simon, who sold it through an art dealer around 1937 to Norwegian ship owner Thomas Olsen.

- ^ JTA (15 October 2012). "Jewish Family Wants 'The Scream' History Explained". The Forward. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Hugo Simon owned the painting in the 1920s and 1930s, but the banker and top art collector was to forced sell it and flee Germany after the Nazis came to power in 1933. His heirs contested the sale before the auction in the spring, but now say it is a moral issue and are calling on MoMA to explain in its display the painting's "tragic history," the Post reported, citing Rafael Cardoso, a Brazilian curator and Simon's great-grandson.

- ^ "News in Brief". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Chung, Jen (14 October 2012). "Man Says MoMA's Loaned 'Scream' Has A Nazi Past". Gothamist. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

Cardoso tried to contest sale ahead of the auction earlier this year, saying, "It is obvious that Hugo Simon has sold the painting under duress, probably under value." He said that the seller's owner, Petter Olsen, offered to donate $250,000 to a charity of his choice

- ^ Michaud, Chris (3 May 2012). ""The Scream" sells for record $120 million at auction". Reuters. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (12 November 2013). "At $142.4 Million, Triptych Is the Most Expensive Artwork Ever Sold at an Auction". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Gamerman, Ellen (26 April 2012). "Selling 'The Scream'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Bertrand, Frank C. (1 November 2002). "Late Night Thoughts about Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, while listening to Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures At An Exhibition". PKD Otaku #7.

- ^ Janov, Arthur (1977). The Primal Scream. New York: Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11834-5.

- ^ "Scream on the Surface". Munch-Museet. Archived from the original on 9 April 2005. Retrieved 29 May 2005.

- ^ Pochin, Courtney (19 October 2019). "People spot something amusing about The Scream painting – and it's hard to unsee". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Royston-Claire, Gem (6 December 2021). "13 things you never knew about the Home Alone movies". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Kendzior, Sarah (January 2000). "The Face of 'Scream'". Fangoria (189). Starlog Group Inc.: 29.

- ^ Masters, Tim (5 April 2011). "Doctor Who boss says season start is 'darkest yet'". BBC. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ "Munchs «Skrik» blir frimerke" [Munch's "Scream" becomes a postage stamp]. NTB (in Norwegian). 13 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Lea, Mathilde (2 April 2018). "Kunsttyv Pål Enger om "Skrik"-tyveriet i ny musikalsk sketsj: – Det var ikke politi i Oslo" [Art thief Pål Enger about the "Scream" theft in a new musical sketch: There were no police in Oslo]. Dagbladet (in Norwegian).

- ^ "Facial Neuralgia Resources". Trigeminal Neuralgia Resources / Facial Neuralgia Resources. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "😱 Face Screaming in Fear". Emojipedia. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ "Permanent Markers Implementation Plan" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. 19 August 2004. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Claes, Koenraad (October 2018), "The Little Magazine as a Periodical Portfolio: the Dial, the Pagan Review and the Page", The Late-Victorian Little Magazine, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 64–106, doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9781474426213.003.0004, ISBN 978-1-4744-2621-3, S2CID 181470552, retrieved 3 March 2022

Further reading

[edit]- Temkin, Ann (2012) The Scream: Edvard Munch, Museum of Modern Art

- Heller, Reinhold (1973). Edvard Munch: The Scream. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-07-139-0276-1.

External links

[edit]- Edvard Munch – Biography and Paintings Archived 11 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Munch and The Scream – Discussion in the In Our Time series on the BBC.

- The Scream – Zoomable version

- The Scream – Zoomable version, biography and article about the painting at The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design