Jeremy Hardy

| Jeremy Hardy | |

|---|---|

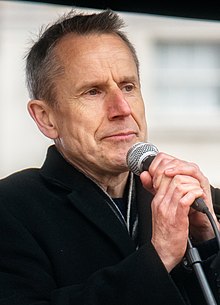

Hardy in 2016 | |

| Birth name | Jeremy James Hardy |

| Born | 17 July 1961 Farnborough, Hampshire, England |

| Died | 1 February 2019 (aged 57) London, England |

| Medium | Television, radio and stand-up |

| Education | University of Southampton (BA) |

| Spouse | Kit Hollerbach (1986–2006) Katie Barlow |

| Children | 1 (adopted) |

Jeremy James Hardy (17 July 1961 – 1 February 2019) was an English comedian. Born and raised in Hampshire, Hardy studied at the University of Southampton and began his stand-up career in the 1980s, going on to win the Perrier Comedy Award at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1988. He is best known for his appearances on radio panel shows such as the News Quiz and I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue.

Early life

[edit]Hardy was born in Farnborough, Hampshire,[1][2] the fifth and youngest child of rocket scientist Donald D. Hardy (1925–2016) and Sheila Stagg (1924–2012).[3] He attended Farnham College and studied modern history and politics at the University of Southampton.[1] He subsequently failed to obtain a place on a journalism course, and considered becoming an actor or poet.[4]

Career

[edit]Hardy started scriptwriting before turning to stand-up comedy in London in the early 1980s,[4] funded in part by the Enterprise Allowance Scheme.[5] He won the Perrier Comedy Award in 1988 at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

He made his television debut in the late 1980s, featuring regularly as Jeremy the boom operator in the Rory Bremner-led comedy show Now – Something Else on BBC Two, along with guest appearances on programmes including the BBC One talk show Wogan.[4] He went on to feature in various comedy shows including Blackadder Goes Forth (1989), and presented a television documentary about the political background to the English Civil War as well as an edition of Top of the Pops in 1996. He was one of the two team captains on the BBC Two game show If I Ruled the World that ran for two series in 1998–1999.[4] Kit Hollerbach featured alongside him in the BBC radio sitcoms Unnatural Acts and At Home with the Hardys.[6][7]

Hardy worked extensively on BBC Radio 4, particularly on The News Quiz, I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue and his long-running series of monologues Jeremy Hardy Speaks to the Nation.[8] His excruciatingly off-key singing was a long-running joke on the radio panel show I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue — on which he appeared regularly — as well as the spin-off radio series You'll Have Had Your Tea: The Doings of Hamish and Dougal.[9] He appeared in the Radio 4 sitcom Linda Smith's A Brief History of Timewasting,[10] and he also appeared as a panellist on the first and second series of QI.[11] His experiences in Palestine during the Israeli army incursions of 2002 became the subject of a feature documentary Jeremy Hardy vs. the Israeli Army (2003), directed by Leila Sansour. A four-episode series entitled Jeremy Hardy Feels It was broadcast on Radio 4 in December 2017 to January 2018.[12]

Hardy wrote a regular column for The Guardian until 2001.[13] He then wrote a column in the London Evening Standard's magazine.[4] His first book, When Did You Last See Your Father, was published by Methuen in 1992. My Family and Other Strangers, based on his research into his family history, was published by Ebury Press on 4 March 2010.[14]

An anthology of Hardy's writing, Jeremy Hardy Speaks Volumes, was published in February 2020.[15] It was edited by his wife Katie Barlow and his long-time radio producer David Tyler.[16]

Political views

[edit]Hardy was a committed socialist, and a supporter of the Labour Party. He performed at Labour Party rallies and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn considered him a "dear, lifelong friend".[17] His comedy embodied his radical politics, including outspoken opposition to former Labour leader Tony Blair[18] – he was conflicted during the Blair and Gordon Brown leadership period, quoted as saying "To me, voting Labour is like wiping your bottom: I can't say I like doing it but you've got to – because you're in a worse mess if you don't."[19] Hardy was banned from voting in Labour internal elections in 2015 because he had also raised funds for the Green Party.[20] He strongly supported Corbyn in the leadership election of 2015.[21] He was also an outspoken opponent of the Trident programme.[22]

Hardy supported Irish nationalist Róisín McAliskey, the then-pregnant daughter of Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, when the former was accused of involvement in an IRA mortar attack in Germany, and put up part of the bail money to free her.[8] He also supported the campaign to free Danny McNamee, whose conviction for involvement in the Provisional Irish Republican Army's (IRA) Hyde Park bombing on 20 July 1982 was quashed in 1999, after several years of prison.[23]

In an edition of Jeremy Hardy Speaks to the Nation on BBC Radio 4 "How to be Afraid", broadcast in September 2004, Hardy said during one of his comedy routines that "if you just took everyone in the BNP and everyone who votes for them and shot them in the back of the head, there would be a brighter future for us all."[24] This sparked complaints and caused Burnley Borough Council to cancel a show in the town over fears that it could be "disruptive" in an area with a recent history of racial tension.[25]

In September 2016 Hardy performed at the Keep Corbyn rally in Brighton in support of Jeremy Corbyn's campaign in the Labour Party leadership election.[26] On Hardy's death, Corbyn said "He always gave his all for everyone else and the campaigns for social justice."[17]

Personal life

[edit]In 1986 Hardy married the actress and comedian Kit Hollerbach[2] and in 1990 they adopted a daughter, Elizabeth Hardy. He later married the photographer and filmmaker Katie Barlow.[27]

Hardy was a close friend of the comedian Linda Smith; when she died of ovarian cancer on 27 February 2006 he publicly eulogised her in many media outlets[28] and wrote her obituary in The Guardian.[29]

Hardy died at St Christopher’s Hospice in Sydenham, London of cancer on 1 February 2019, at the age of 57.[2][27] Julia McKenzie, the head of Radio team at BBC Studios, said of Hardy "I will remember him as someone who could convulse an audience with laughter at a comic image whilst at the same time making a point of substance that reverberated on a much deeper level and spoke to his principles and unflinching concern for the less fortunate."[30] Miles Jupp, then-host of The News Quiz and a longtime friend, wrote his obituary in The Guardian.[1]

Collections

[edit]The University of Kent holds a collection of Hardy's work as part of the British Stand-Up Comedy Archive.[31] The archive is composed of audio-visual material from Hardy's career, including recordings of live performances.[31]

Appearances

[edit]Television

[edit]- Helping Henry (1988) – the voice of Henry[32]

- Blackadder Goes Forth (1989) ("Corporal Punishment") – Corporal Perkins[32]

- Jack and Jeremy's Real Lives (1996) (with Jack Dee)

- If I Ruled the World (1998)[32]

- QI (2003)[32]

- Grumpy Old Men (2004)[33]

- Mock the Week (2005)[34]

- Countdown (2007) (Dictionary Corner)[35]

- The Voice (2008)[36]

Radio

[edit]- The News Quiz[8]

- I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue[8]

- Just a Minute[8]

- Jeremy Hardy Speaks to the Nation[8]

- Unnatural Acts[7]

- At Home with the Hardys[6]

- You'll Have Had Your Tea: The Doings of Hamish and Dougal[37]

- Chain Reaction[38][39][40]

- Comic to Comic[41]

- The Unbelievable Truth[42]

- Jeremy Hardy Feels It (2018)[43]

Film

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jupp, Miles (1 February 2019). "Jeremy Hardy obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Double, Oliver (2023). "Hardy, Jeremy James (1961–2019)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000381184. ISBN 9780198614128. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Serena Hardy (17 July 2016). "Donald Hardy obituary". The Guardian, London. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Jeremy's stand-up routine". The Bolton News. 22 February 2002. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ Moorhead, Rosy (19 December 2015). "Jeremy Hardy looks back at 'the one decent thing Thatcher did'". Harrow Times. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ a b "At Home With the Hardys". BBC. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Unnatural Acts". BBC. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Jeremy Hardy: Caustic comic". BBC. 5 April 2002. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Jeremy Hardy – Comedian, Writer and Political Activist". BBC. 6 January 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "A Brief History of Timewasting: The Complete Series 1 and 2". Penguin Books. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Jeremy Hardy Dies at 57". Nottinghamshire Live. February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "Jeremy Hardy Feels It". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ Hardy, Jeremy (4 April 2001). "Frankly, I've got nothing to joke about". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ Hardy, Jeremy (27 February 2010). "Jeremy Hardy's family tree". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ Hardy, Jeremy (21 October 2019). Jeremy Hardy Speaks Volumes. John Murray Press. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Merritt, Stephanie (15 February 2020). "'I knew he was loved but not the scale of it': Katie Barlow on her late husband Jeremy Hardy". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b Mumford, Gwilym (1 February 2019). "Comedian Jeremy Hardy dies of cancer aged 57". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Lawson, Mark (1 February 2019). "Jeremy Hardy: a ferocious talent who radicalised radio comedy". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Turner, Alwyn W (22 March 2012). "Things can only get bitter". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "The Labour purge is underway". New Internationalist. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "Comic Jeremy Hardy accuses Labour of trying to rig leadership election". The Guardian. Press Association. 21 August 2015. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "Comedian Jeremy Hardy is under fire for suggesting Trident supporters are mentally ill". 10 March 2016. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "McNamee's 11-year campaign for justice". BBC News. 17 December 1998. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ "Jeremy Hardy Speaks to the Nation s06e01 How to Be Afraid" – via vimeo.com.

- ^ "Comic banned for 'shoot BNP' joke". BBC News. 2 November 2004. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ Burke, Darren (26 August 2016). "TV star comedians line up for Jeremy Corbyn rally in Doncaster". Doncaster: Doncaster Free Press. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Jeremy Hardy: Comedian and Radio 4 panel star dies aged 57". BBC. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Hardy, Jeremy (28 February 2006). "Her mind was extraordinary". BBC News. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ Hardy, Jeremy (1 March 2006). "Obituary: Linda Smith". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ McKenzie, Julia (1 February 2019). "The News Quiz twitter feed" (Press release). Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Jeremy Hardy Collection". Special Collections and Archives - University of Kent. 6 December 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Jeremy Hardy". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Grumpy Old Men". Radio Times (4198): 108. 2 September 2004. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Mock the Week". Radio Times (4236): 74. 2 June 2005. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Collier, Hatty (1 February 2019). "Jeremy Hardy death: Comedian dies from cancer aged 57". Evening Standard. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "The Voice". Radio Times (4370): 124. 17 January 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Daoust, Phil (25 February 2004). "Radio: Pick of the day". The Guardian.

- ^ "Chain Reaction". Radio Times (4322): 123. 8 February 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Chain Reaction – Series 3 – Jeremy Hardy". BBC Radio 4. 14 February 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Chain Reaction – Series 3 – Jack Dee interviews Jeremy Hardy". BBC Radio 4 Extra. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Comic to Comic". Radio Times (4298): 127. 17 August 2006.

- ^ "The Unbelievable Truth". Radio Times (4306): 133. 12 October 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Jeremy Hardy Feels It". BBC. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Groves, Nancy (22 May 2009). "Observations: Oliver Irving gets by with a little help from his friends". The Independent. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2019.