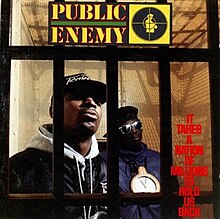

It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back

| It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | June 28, 1988[1] | |||

| Recorded | 1987–1988 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 57:51 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | ||||

| Public Enemy chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back[6] | ||||

| ||||

It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back is the second studio album by American hip hop group Public Enemy, released on June 28, 1988,[7] by Def Jam Recordings and Columbia Records. It was recorded from 1987 to 1988 in sessions at Chung King Studios, Greene St. Recording, and Sabella Studios in New York.

Noting the enthusiastic response toward their live shows, Public Enemy intended to make the album's music at a higher tempo than their 1987 debut Yo! Bum Rush the Show for performance purposes. The group also set out to create the hip hop equivalent of Marvin Gaye's What's Going On (1971), an album noted for its strong social commentary. Through their production team the Bomb Squad, Public Enemy introduced a densely aggressive sound influenced by free jazz, heavy funk, and musique concrète as a backdrop for lead rapper Chuck D, who employed sociopolitical rhetoric, revolutionary attitudes, and dense vocabulary in his performances.[8]

It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back charted for 47 weeks on the US Billboard 200, peaking at number 42, and was certified Platinum by the RIAA in 1989. The album received widespread acclaim from critics, who praised its production techniques and Chuck D's socially and politically charged lyricism. It also appeared on many publications' year-end top album lists for 1988 and was the runaway choice as the best album of 1988 in The Village Voice's Pazz & Jop critics' poll, a poll of the leading music critics in the US.[9]

Since its initial reception, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back has been regarded by music writers and publications as one of the greatest and most influential albums of all time.[10][11] In 2000, it was voted number 92 in Colin Larkin's book All Time Top 1000 Albums,[12] and in 2003, it was ranked number 48 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, the highest ranking of all the hip hop albums on the list, and the only one acknowledged in the top 100. In the 2020 version of the same list, the album was ranked number 15, while other hip-hop albums moved into the top 100.

Background

[edit]Public Enemy's 1987 debut album Yo! Bum Rush the Show, while acclaimed by hip hop critics and aficionados, had gone ignored for the most part by the rock and R&B mainstream,[13] selling only 300,000 copies, which was relatively low by the high-selling standards of other Def Jam recording artists such as LL Cool J and Beastie Boys at the time.[14] However, the group continued to tour and record tirelessly. "On the day that Yo! Bum Rush the Show was released [in the spring of 1987], we was already in the trenches recording Nation of Millions," stated lead MC Chuck D.[15][16]

With It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, the group set out to make what they considered to be the hip hop equivalent to Marvin Gaye's What's Going On, an album noted for its strong social commentary.[17] As said by Chuck, "our mission was to kill the 'Cold Gettin' Dumb' stuff and really address some situations."[17] In order to ensure that their live shows would be as exciting as those they played in London and Philadelphia, the group decided that the music on Nation of Millions would have to be faster than that found on Yo! Bum Rush the Show.[18] "Years of saved-up ideas," noted Chuck, "were compiled into one focused aural missile."[19]

Recording

[edit]It wasn't that we took records and rapped over them, we actually had an intricate way of developing sound, arranging the sound. We had musicians like Eric Sadler... Hank Shocklee, the Phil Spector of hip hop. You've got to give the credit as it's due, if Phil Spector has the Wall of Sound Hank Shocklee has the Wall of Noise.

— Chuck D, The Quietus, 2008[20]

Public Enemy began making the album at Chung King Studios in Manhattan but ran into conflicts with engineers prejudiced against hip hop acts.[21] The group resumed recording at Greene St. Recording where they were more comfortable.[17] Initially, the engineers at Greene Street were also apprehensive about the group but eventually grew to respect their work ethic and seriousness about the recording process.[17] Recorded under the working title Countdown to Armageddon, the group ultimately decided on It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back instead, a line from their first album's song "Raise the Roof".[22] The material was recorded in 30 days for an estimated $25,000 in recording costs,[23] due to an extensive amount of preproduction by the group at their Long Island studio.[23] The album was completed in six weeks.[24] "It was aggressive, race-against-the-clock teamwork, taking chances in sound," recalled Chuck D.[19]

Rather than touring with the rest of the group, Eric "Vietnam" Sadler and Hank Shocklee would stay in the studio and work on material for the Nation of Millions album, so that the music was ready when Chuck D and Flavor Flav returned from tour.[15] When the group began planning the second album, the songs "Bring the Noise", "Don't Believe the Hype", and "Rebel Without a Pause" had already been completed.[18] The latter track was recorded during the group's 1987 Def Jam tour, and the lyrics were written by Chuck D in one day spent secluded at his home.[25] Instead of looping the break from James Brown's "Funky Drummer", a commonly used breakbeat in hip hop, "Rebel Without a Pause" had Flavor Flav play the beat on the drum machine continuously for the track's duration of five minutes and two seconds.[25] Chuck D later said of his contribution to the track, "Flavor's timing helped create almost like a band rhythm".[25] Terminator X, the group's DJ/turntablist, also incorporated a significant element to the track, the renowned transformer scratch, towards its end. Named for its similarity to the sound made by the Autobots in The Transformers, the scratch was developed by DJ Spinbad and popularized by DJ Jazzy Jeff and Cash Money, and Terminator X had honed his take on the scratch on tour.[25] The group was satisfied with its sound after having removed the bass from his section of the track.[25]

According to Chuck D, Hank Shocklee made the last call when songs were completed. "Hank would come up with the final mix because he was the sound master... Hank is the Phil Spector of hip-hop. He was way ahead of his time, because he dared to challenge the odds in sound."[22] This was also one of the details which Chuck felt to be unique to the time and recording of the album. "Once hip-hop became corporate, they took the daredevil out of the artistry. But being a daredevil was what Hank brought to the table."[22] It was decided amongst the group that the album should be exactly one hour long, thirty minutes on each side. At the time, audio cassettes were more popular than CDs and the group did not want listeners having to hear dead air for a long time after one-half of the album was finished.[26] The two sides of the album were originally the other way around, the album beginning with "Show Em Whatcha Got" which leads into "She Watch Channel Zero?!". This instead became the start of side two or the "Black Side". Hank Shocklee decided to flip the sides just before the mastering of the album and start the record with Dave Pearce introducing the group during their first tour of England.[22][26]

Music and lyrics

[edit]Under Hank Shocklee's direction, the Bomb Squad, the group's production team, began to develop a dense and chaotic production style that relied on found sounds and avant-garde noise as much as it did on old-school funk.[13] Along with a varied selection of sampled elements, the tracks feature a greater tempo than those of the group's contemporaries.[27] Music critic Robert Christgau noted these elements and wrote that the Bomb Squad "juice post-Coleman/Coltrane ear-wrench with the kind of furious momentum harmolodic funk has never dared: the shit never stops abrading and exploding".[28] As with the group's live performances, Flavor Flav supported Chuck D's politically charged lyrics with "hype man" vocals and surrealistic lyrics on the album.[29][30]

On the album's content, music journalist Peter Shapiro wrote "Droning feedback, occasional shards of rock guitar, and James Brown horn samples distorted into discordant shrieks back the political rhetoric of lead rapper Chuck D and the surreality of Flavor Flav".[29] Ethnomathematics author Ron Eglash interpreted the album's style and production to be "massively interconnected political and sonic content", writing that "[the Bomb Squad] navigated the ambiguity between the philosophies of sound and voice. Public Enemy's sound demonstrated an integration of lyrical content, vocal tone, sample density and layering, scratch deconstruction, and sheer velocity that rap music has never been able to recapture, and that hip-hop DJs and producers are still mining for gems".[27]

We took whatever was annoying, threw it into a pot, and that's how we came out with this group. We believed that music is nothing but organized noise. You can take anything—street sounds, us talking, whatever you want—and make it music by organizing it. That's still our philosophy, to show people that this thing you call music is a lot broader than you think it is.

— Hank Shocklee, Keyboard Magazine, 1990[31]

In an interview with the New York Daily News, Shocklee noted that the album's dynamic sound was inspired by Chuck D's rapping prowess, stating "Chuck's a powerful rapper. We wanted to make something that could sonically stand up to him".[24] Of his own contributions to its production, Shocklee cited himself as being the arranger and noted that he had "no interest in linear songs".[23] When using records for sampling, Shocklee stated that he'd sometimes put them on the ground and stomp on them if they sounded too "clean."[23]

Hank referred to Chuck D as being the person who would find all the vocal samples, Eric Sadler as "the one with the musical talent," and noted that his brother, Keith Shocklee, "knew a lot of the breakbeats and was the sound-effects master."[23] Shocklee's sentiments were reinforced by Chuck D while explaining the group's working methods during production. "Eric was the musician, Hank was the antimusician. Eric did a lot of the [drum] programming, [Hank's brother] Keith was the guy who would bring in the feel."[15] For his contributions to the production side, Chuck stated that he "would scour for vocal samples all over the Earth. I would name a song, tag it, and get the vocal samples."[15] Chuck D also noted the productiveness of Sadler and Shocklee's differing approaches to the creative process. "The friction between Hank and Eric worked very well. Hank would put a twist on Eric's musicianship and Eric's musicianship would put a twist on Hank."[22]

Some production mistakes were kept for the album. The breakdown in "Bring the Noise" in which the kick-drum sample from James Brown's "Funky Drummer" plays solo was a mistake.[23] Apparently, the wrong sequence came up in the SP1200 sampler and Shocklee decided not only to keep it but to have Chuck rewrite his rhyme to fit the pattern.[23] The album itself was mixed with no automation, instead of being recorded on analog tape and later painstakingly mixed by hand.[23] This is a significant fact due to its nature as being one of the most intricate albums of digitally sampled music.[23] Asked years later if replicating the number of samples used on the album would be possible [due to increased clearance costs for copyrighted material], Hank Shocklee said while possible, it would be far more expensive.[32]

Songs

[edit]Throughout the album, Chuck D delivers narratives that are characterized by black nationalist rhetoric and regard topics such as self-empowerment for African Americans, critiques of white supremacy, and challenges to exploitation in the music industry.[33] "Caught, Can We Get a Witness?" directly addresses the issue of sampling in hip hop and copyright violation from a perspective that supports the practice and claims entitlement due to "black ownership of the sounds in the first place".[33]

"Rebel Without a Pause" exemplifies the faster tempo that Public Enemy intended for the album,[25] while incorporating a heavy beat and samples of screeching horns,[34] the latter taken from the J.B.'s' "The Grunt" (1970).[33] According to Ron Eglash, such effects of sampling exemplify the "sense of urgency" given to the messages of the album's tracks, "to heighten the tension of the mix", while Chuck D's message is "one of total resistance that was readily accessible through [...] the confrontational sounds of bass, groove, and noise."[33] Lyrically, it eschews the traditional verse/chorus—verse/chorus song structure, with 12 bars of Chuck D's aggressive rapping, punctuated by Flavor Flav's stream of consciousness ad-libs.[25] Public Enemy-biographer Russell Myrie writes of the track's significance, "It matched 'I Know You Got Soul' in terms of its innovation and its breathtaking quality. It increased the tempo for Public Enemy, something they would do repeatedly during their forthcoming masterpiece [...] The faster tempo was important as it would heighten energy levels at their shows. Most important of all, it sounded fresh. It was some next level hip-hop. Chuck and Hank rightly felt it could stand alongside the best rap records of the time."[25]

Some of the song titles make reference to other works from popular culture. The title of the song "Party for Your Right to Fight" is a rearrangement of the Beastie Boys' 1987 hit single "(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!)."[35] The vocal sample of hip hop DJ Mr. Magic stating that his show would play "no more music by the suckers" was used on the song "Cold Lampin' with Flavor" after having been recorded from Magic's radio show by Flavor Flav.[36] Magic had dissed the group with the line when he mistakenly embroiled them in the WBAU-WBLS radio war.[36]

Chuck D has said that "Party for Your Right to Fight", the album's closing track, is dedicated to the Black Panther Party.[37]

Release and reception

[edit]The album was released on June 28, 1988 and in its first month of release, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back sold 500,000 copies without significant promotional efforts by its distributing label Columbia Records.[38][39] It peaked at number 42 on the U.S. Billboard Top Pop Albums chart and at number one on the Top Black Albums chart.[40] It spent 49 weeks on the Billboard Top Pop Albums.[41] On August 22, 1989, it was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), for shipments of at least one million copies in the United States.[42] Since 1991, when the tracking system Nielsen SoundScan began tracking domestic sales data, the album has sold 722,000 additional copies as of 2010[update].[43]

It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back received positive reviews from contemporary critics. In his review for Rolling Stone, David Fricke described the album as a "Molotov cocktail of nuclear scratching, gnarly minimalist electronics and revolution rhyme" and complimented its "abrupt sequencing and violent sonic compression of rapid-fire samples, slamming-jail-door percussion, DJ Terminator X's tornado turntable work and Chuck D's outraged oratory".[44] Los Angeles Times writer Robert Hilburn said that the album incorporates some of the dynamics of early rap records such as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five's "The Message" (1982) and Run–D.M.C.'s "Sucker M.C.'s" (1983) with the "radical, socially conscious tradition of groups like the Last Poets".[14] Hilburn commended Chuck D for his rapping on It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, writing that he "isn't afraid of being labeled an extremist, and it's that fearless bite—or game plan—that helps infuse his black-consciousness raps with the anger and assault of punk pioneers like the Sex Pistols and Clash".[45] Writing for NME, critic James Brown said that "Nation of Millions... is impressive because it moves, it uses and it's a music—not the acetate-thin barrage of whingeing and boasting that so often passes for rap",[46] while in Q, David Sinclair called it "an unimaginably urgent album seething with vengeful rage and booby trapped with incendiary musical devices".[47] Jon Pareles of The New York Times praised the album for its production and compared its symbolic value to hip hop music at the time, stating:

Where most rappers present themselves as funky individualists, beating the odds of the status quo, Public Enemy suggests that rap listeners can become an active community, not just an audience. Although it overreaches, It Takes a Nation jams urban tension and black anger into the foreground; it reveals the potential for demagoguery as well as the need for change. 'Whatcha gonna do/ rappers not afraid of you', Public Enemy demands, and in 1988 it sounds like something more than idle entertainment.[48]

Despite writing that it "sounds powerful, fresh and galvanizing", Mark Jenkins of The Washington Post found its lyrical content inconsistent, stating "Aurally, 'Nation of Millions' is intoxicating; Hank Shocklee and Carl Ryder's bold production will likely prove among the most distinctive of the year, not just in rap but in any pop genre. For their work to pack the political wallop they crave, however, the members of Public Enemy need to think for themselves, not just attach themselves to the thought of whichever black nationalist is currently drawing big crowds".[49] The Los Angeles Daily News gave the album a "B" and compared its musical "rage" to that of rapper Schoolly D's Smoke Some Kill (1988).[50]

In its year-end list of 1988's best albums, Q called It Takes a Nation "a blistering collage of beat box [sic], rock guitar, police-radio chatter and high-velocity rapping."[51] It was voted number one in The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics' poll,[52] as well as number three on poll creator Robert Christgau's list.[53] In an article for the newspaper, Christgau called it "the bravest and most righteous experimental pop of the decade—no matter how the music looks written down (ha ha), Hank Shocklee and Terminator X have translated Blood Ulmer's harmolodic visions into a street fact that's no less edutaining (if different) in the dwellings of monkey spawn and brothers alike (and different)".[54]

Legacy and influence

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A+[56] |

| The Guardian | |

| NME | 10/10[58] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[59] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Select | 5/5[62] |

| The Source | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 10/10[64] |

It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back has been cited by critics and publications as one of the greatest and most influential recordings of all time.[10][11] Upon the album's remastered reissue in 1995, Q hailed it "the greatest rap album of all time, a landmark and classic".[60] Melody Maker called the album "bloody essential", commenting, "I hadn't believed it could get harder [than Yo! Bum Rush the Show]. Or better."[65] NME dubbed it "the greatest hip-hop album ever" at the time, stating "this wasn't merely a sonic triumph. This was also where Chuck wrote a fistful of lyrics that promoted him to the position of foremost commentator/documentor of life in the underbelly of the USA".[58]

Readers of Hip Hop Connection voted it the best album of all-time, prompting the magazine to comment, "Even 'Rebel Without a Pause', a definite contender for best rap single ever released, failed to put the other 12 [sic] tracks to shame, such was the high standard throughout."[66] HHC readers again voted it the best of all-time in 2000, as did Flavor Flav in his accompanying top ten. "This is really hard," he said, "because I'm in love with every piece of work that's ever been recorded. I would never say someone else's project is better than anyone else's."[67]

Mojo stated upon the album's 2000 European reissue, "Responsible for the angriest polemic since The Last Poets....[they] revolutionized the music, using up to 80 backing tracks in the sonic assault....to these ears PE sound like the greatest rock'n'roll band in history".[68] In 2003, Rolling Stone ranked the album number 48 on its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, making it the highest-ranked of the 27 hip hop albums included on the list,[69] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list.[70] Time magazine hailed it as one of the 100 greatest albums of all time in 2006.[71] Kurt Cobain, the lead guitarist and singer of rock band Nirvana, listed the album as one of his top 50 favorite albums in his Journals.[72] In 2006, Q placed the album at number seven on its list of "40 Best Albums of the '80s".[73] In 2012, Slant Magazine listed the album at #3 on its list of "Best Albums of the 1980s" behind Michael Jackson's Thriller and Prince and the Revolution's Purple Rain.[74] The album ranks Number 2 on the list of best records of the 20th century of German music magazine Spex.[75]

In his 2004 book Appropriating Technology: Vernacular Science and Social Power, Ron Eglash commented that a sonically and politically charged album such as Nation "can be considered a monument to the synthesis of sound and politics".[27] In 2005, New York University's Clive Davis Department of Recorded Music hosted a two-day retrospective called "The Making of It Takes a Nation of Millions."[23] It featured a producers' panel that reunited Hank Shocklee, captain of the Bomb Squad, with the Chairmen of the Boards from Greene St. Recording.[23] When asked in 2008 if the album would still be considered as radical if it were released two decades later, Chuck D said he felt it would "simply because it's faster than anything on the radio right now. And yeah, it's radical politically... because it's not really being said a lot. You want it to not be radical, but it is because it's totally different from Soulja Boy."[76] American rapper Ice Cube said in 2005 that the album "messes with your brain even to this day."[77] The album's revolutionary attitudes also influenced musician and activist Kathleen Hanna of the seminal riot grrrl band Bikini Kill. She described it as her go-to album while touring, stating: "I was like, 'Man, some of these rappers are bragging and boasting, and I wanna brag and boast!' Like, why do I feel like I have to try to write the song I'm supposed to write, and not the song I wanna write?"[78]

"The title alone was incredible to me. The artwork was amazing. As a body of work, it just blew me away…. I saw what that album did to the world. It helped bring me closer to understanding what's required to be an artist of that calibre." – Busta Rhymes[79]

Public Enemy performed the album in its entirety as part of the All Tomorrow's Parties-curated Don't Look Back series.[20] "I didn't think it would work," Chuck D admitted of the full-length performance. "But it ended up being something that worked tremendously well. Now we have a problem to get away from it. It amazed me that a lot of people who have gravitated to the album weren't even born when it was recorded. But it's YouTube and iLike and MySpace and file sharing which highlighted the existence of it. So I can't shoot down file sharing, as it's benefited us tremendously."[80]

Music from the album has been sampled over the years, including (though not limited to) the Beastie Boys ("Egg Man"),[81] Game ("Remedy"),[82] The album is broken down track-by-track by Chuck D in Brian Coleman's book Check the Technique.[83]

Accolades

[edit]| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| About.com | USA | 100 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums[84] | 2008 | 2 |

| 10 Essential Hip-Hop Albums[85] | 2008 | 2 | ||

| Adresseavisen | Norway | The 100 (+23) Best Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1995 | 41 |

| Aftenposten | Top 50 Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1999 | 4 | |

| Alternative Press | USA | Top 99 Albums of '85 to '95[citation needed] | 1995 | 6 |

| Amazon.com | The 10 Best Albums by Decade[citation needed] | 1999 | 1 | |

| The Anarchist | UK | The 33 Best Albums Ever[citation needed] | 1997 | 4 |

| BigO | Singapore | The 100 Best Albums from 1975 to 1995[citation needed] | 1995 | 29 |

| Blender | USA | The 100 Greatest American Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2002 | 11 |

| 500 CDs You Must Own Before You Die[citation needed] | 2003 | * | ||

| Blow Up | Italy | 600 Essential Albums[citation needed] | 2005 | |

| Channel 4 | UK | 125 Nominations for the 100 Greatest Albums[citation needed] | ||

| Robert Christgau | USA | Personal 10 Best Albums from the '80s[citation needed] | 1990 | 8 |

| The Courier-Mail | Australia | 50 Defining Rock Albums[citation needed] | 2005 | 42 |

| Dagbladet | Norway | The Best Albums of the Century[citation needed] | 1999 | * |

| Dance de Lux | Spain | The 25 Best Hip-Hop Records[citation needed] | 2001 | 1 |

| Robert Dimery (General Editor) | — | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[86] | 2016 | * |

| Discoplay | Spain | The 50 Best Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1997 | |

| Eggen & Kartvedt | Norway | The Guide to the 100 Important Rock Albums[citation needed] | 1999 | |

| Ego Trip | USA | Hip Hop's 25 Greatest Albums by Year 1980–98[citation needed] | 1 | |

| Entertainment Weekly | The 100 Greatest CDs of All Time[citation needed] | 1993 | 33 | |

| Expressen | Sweden | The 100 Best Records Ever[citation needed] | 1999 | 66 |

| The Face | UK | Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 9 |

| Fast 'n' Bulbous | USA | The 500 Best Albums Since 1965[citation needed] | — | 80 |

| Gear | The 100 Greatest Albums of the Century[citation needed] | 1999 | 14 | |

| The Guardian | UK | The 100 Best Albums Ever[citation needed] | 1997 | 20 |

| Joe S. Harrington, Blastitude | USA | The All-Time Top 100 Albums[citation needed] | 2001 | 27 |

| Helsingin Sanomat | Finland | 50th Anniversary of Rock[citation needed] | 2004 | * |

| IE | USA | 50 Great Albums, a Rock Time Capsule[citation needed] | 1999 | |

| Juice TV | Australia | The 50 Best Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1997 | 19 |

| KCPR DJs | USA | Top 100 Records from the 80s[citation needed] | 2002 | 43 |

| Kitsap Sun | Top 200 Albums of the Last 40 Years[citation needed] | 2005 | 53 | |

| David Kleijwegt | Netherlands | Top 100 Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1999 | 47 |

| Les Inrockuptibles | France | The 100 Best Albums 1986–1996[citation needed] | 1996 | 44 |

| 50 Years of Rock'n'Roll[citation needed] | 2004 | * | ||

| List by Asian Critics | — | 100 Essential Albums[citation needed] | — | |

| Melody Maker | UK | Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 28 |

| All Time Top 100 Albums[citation needed] | 2000 | 17 | ||

| Mojo | The 100 Greatest Albums Ever Made[citation needed] | 1995 | 76 | |

| Tom Moon | USA | 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die[87] | 2008 | * |

| Paul Morley | UK | Words and Music, 5 x 100 Greatest Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2003 | * |

| Musik Express/Sounds | Germany | The 100 Masterpieces[citation needed] | 1993 | 92 |

| The 50 Best Albums from the 80s[citation needed] | 2003 | 3 | ||

| Muzik | UK | The 50 Most Influential Records of All Time[citation needed] | * | |

| Top 50 Dance Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2002 | 19 | ||

| New Musical Express | 40 Records That Captured the Moment 1952–91[citation needed] | 1992 | * | |

| Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 1 | ||

| All Times Top 100 Albums + Top 50 by Decade[citation needed] | 1993 | 9 | ||

| Top 100 Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2003 | 29 | ||

| New Nation | Top 100 Albums by Black Artists[citation needed] | — | 3 | |

| Nieuwe Revu | Netherlands | Top 100 Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1994 | 34 |

| NPR | USA | The 300 Most Important American Records of the 20th Century[citation needed] | 1999 | * |

| OOR | Netherlands | Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 4 |

| The Best Albums of 1971–1991[citation needed] | 1991 | 1 | ||

| The Best Albums of the 80s[citation needed] | 1989 | |||

| Panorama | Norway | The 30 Best Albums of the Year 1970–98[citation needed] | 1999 | 12 |

| Pause & Play | USA | 10 Albums of the 80's[citation needed] | 2003 | * |

| Albums Inducted into a Time Capsule, One Album per Week[citation needed] | — | |||

| Pitchfork | Top 100 Favorite Records of the 1980s[citation needed] | 2002 | 9 | |

| Platekompaniet | Norway | Top 100 Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2001 | 54 |

| Pop | Sweden | The World's 100 Best Albums + 300 Complements[citation needed] | 1994 | 15 |

| Pure Pop | Mexico | The 10 (+50) Most Important Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2004 | 1 |

| The Best Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1993 | 21 | ||

| Q | UK | The 80 Best Records of the 80s[citation needed] | 2006 | 7 |

| Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | * | ||

| In Our Lifetime: Q's 100 Best Albums 1986–94[citation needed] | 1995 | |||

| Top 20 Albums from 1980 to 2004[citation needed] | 2004 | 9 | ||

| Top 20 Albums from the Lifetime of Q (1986–2006)[citation needed] | — | * | ||

| The Ultimate Music Collection[citation needed] | 2005 | |||

| Radio WXPN | USA | The 100 Most Progressive Albums[citation needed] | 1996 | 28 |

| Record Collector | UK | 10 Classic Albums from 21 Genres for the 21st Century[citation needed] | 2000 | * |

| Record Mirror | Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 1 | |

| The Review | USA | 100 Greatest Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2001 | 13 |

| Rock de Lux | Spain | The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s[citation needed] | 1990 | 4 |

| The 200 Best Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2002 | 5 | ||

| Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 1 | ||

| Rolling Stone | Germany | The 500 Best Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2004 | 345 |

| Mexico | The 100 Greatest Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 11 | ||

| USA | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2003 | 48 | |

| Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 3 | ||

| The Essential 200 Rock Records[citation needed] | 1997 | * | ||

| Slant Magazine | Top 25 Electronic Albums[citation needed] | 2005 | 26 | |

| Soundi | Finland | The 50 Best Albums of All Time + Top 10 by Decade[citation needed] | 1995 | 8 |

| Sounds | UK | Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 20 |

| The Source | USA | The 100 Best Rap Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 1998 | * |

| Spex | Germany | The 100 Albums of the Century[citation needed] | 1999 | 2 |

| Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 3 | ||

| Spin | USA | Top 100 Alternative Albums[88] | 1995 | 2 |

| Top 100 (+5) Albums of the Last 20 Years[citation needed] | 2005 | |||

| The Sun | Canada | The Best Albums from 1971 to 2000[citation needed] | 2001 | * |

| Switch | Mexico | The 100 Best Albums of the 20th Century[citation needed] | 1999 | |

| Tempo | Germany | The 100 Best Albums from the 80's[citation needed] | 1989 | 4 |

| Terrorizer | UK | The 100 Most Important Albums of the 80s[citation needed] | 2000 | * |

| Time | USA | Top 100 Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 2006 | |

| Treble | The Best Albums of the 80s, by Year[citation needed] | 3 | ||

| Uncut | UK | 100 Rock and Movie Icons[citation needed] | 2005 | 55 |

| Various writers | — | Albums: 50 Years of Great Recordings[citation needed] | * | |

| VH1 | USA | The 100 Greatest Albums of R 'N' R[citation needed] | 2001 | 20 |

| Vibe | 100 Essential Albums of the 20th Century[citation needed] | 1999 | * | |

| 51 Albums representing a Generation, a Sound and a Movement[citation needed] | 2004 | |||

| The Village Voice | Albums of the Year[citation needed] | 1988 | 1 | |

| Rickey Vincent | Five Star Albums from "FUNK: The MUSIC, the PEOPLE, and the RHYTHM[citation needed] | — | * | |

| VPRO | Netherlands | 299 Nominations of the Best Album of All Time[citation needed] | 2006 | |

| Wiener | Austria | The 100 Best Albums of the 20th Century[citation needed] | 1999 | 19 |

| Yedioth Ahronoth | Israel | Top 99 Albums of All Time[citation needed] | 91 |

Track listing

[edit]All tracks produced by the Bomb Squad.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Countdown to Armageddon" (Intro) | 1:40 | |

| 2. | "Bring the Noise" |

| 3:46 |

| 3. | "Don't Believe the Hype" |

| 5:19 |

| 4. | "Cold Lampin' with Flavor" |

| 4:17 |

| 5. | "Terminator X to the Edge of Panic" |

| 4:31 |

| 6. | "Mind Terrorist" (Interlude) |

| 1:21 |

| 7. | "Louder Than a Bomb" |

| 3:37 |

| 8. | "Caught, Can We Get a Witness?" |

| 4:53 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9. | "Show 'Em Whatcha Got" (Interlude) |

| 1:56 |

| 10. | "She Watch Channel Zero?!" |

| 3:49 |

| 11. | "Night of the Living Baseheads" |

| 3:14 |

| 12. | "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos" |

| 6:23 |

| 13. | "Security of the First World" (Interlude) |

| 1:20 |

| 14. | "Rebel Without a Pause" |

| 5:02 |

| 15. | "Prophets of Rage" |

| 3:18 |

| 16. | "Party for Your Right to Fight" |

| 3:24 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Bring the Noise (No Noise Version)" | 3:46 |

| 2. | "Bring the Noise (No Noise Instrumental)" | 4:23 |

| 3. | "Bring the Noise (No Noise A Cappella)" | 1:31 |

| 4. | "Rebel Without a Pause (Instrumental)" | 4:23 |

| 5. | "Night of the Living Baseheads (Anti-High Blood Pressure Encounter Mix)" | 5:01 |

| 6. | "Night of the Living Baseheads (Terminator X Meets DST and Chuck Chill Out Instrumental Mix)" | 2:55 |

| 7. | "The Edge of Panic" | 3:00 |

| 8. | "The Rhythm, the Rebel (A Capella)" | 1:11 |

| 9. | "Prophets of Rage (Power Version)" | 3:20 |

| 10. | "Caught, Can We Get a Witness? (Pre Black Steel Ballistic Felony Dub)" | 5:05 |

| 11. | "B-Side Wins Again (Original Version)" | 3:49 |

| 12. | "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos (Instrumental)" | 1:17 |

| 13. | "Fight the Power ("Do the Right Thing" Soundtrack Version)" | 5:23 |

Personnel

[edit]Credits adapted from Allmusic.[89]

- Assistant production – Eric "Vietnam" Sadler

- Engineering – Greg Gordon, John Harrison, Jeff Jones, Jim Sabella, Nick Sansano, Christopher Shaw, Matt Tritto, Chuck Valle

- Executive production – Rick Rubin

- Mixing – Keith Boxley, DJ Chuck Chillout, Steven Ett, Rod Hui

- Photography – Glen E. Friedman

- Production – Carl Ryder, Hank Shocklee

- Production supervisor – Bill Stephney

- Programming – Eric "Vietnam" Sadler, Hank Shocklee

- Turntables – Johnny Juice Rosado, Terminator X

- Vocals – Harry Allen, Chuck D, Fab 5 Freddy, Flavor Flav, Erica Johnson, Professor Griff

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1988) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Netherlands (MegaCharts)[90] | 40 |

| UK Albums Chart[91] | 8 |

| US Billboard Top LPs | 42 |

| US Billboard Top Black Albums | 1 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[92] | Gold | 100,000* |

| United States (RIAA)[93] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Source |Today in Hip Hop History: Public Enemy's 'It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back' Turns 33 Years Old!". 28 June 2021.

- ^ Smith, Chris (2009). 101 Albums that Changed Popular Music. Oxford University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0195373714.

- ^ Cader, Michael, ed. (2002). People: Almanac 2003. Time Home Entertainment. p. 175. ISBN 192904996X.

- ^ Shipley, Al. "10 Ways To Sound Smart Talking About Rap Beats". Complex Magazine. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums". Entertainment Weekly. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Strong (2004), p. 1226.

- ^ "The Source |Today in Hip Hop History: Public Enemy's 'It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back' Turns 33 Years Old!". 28 June 2021.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2008). "All Music Guide Required Listening: Public Enemy". In Woodstra, Chris; Bush, John; Erlewine (eds.). Old School Rap and Hip-Hop. Backbeat Books. p. 70. ISBN 9780879309169.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (February 4, 1990). "Rap—The Power and the Controversy : Success has validated pop's most volatile form, but its future impact could be shaped by the continuing Public Enemy uproar". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- ^ a b Otto, Jeff. "Rolling Stone Essential Albums of the 90s at Rocklist.net". Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^ a b "The Source's 100 Best Rap Albums at Rocklist.net". Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 72. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Public Enemy Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ a b Hilburn, Robert. "Public Enemy's Chuck D: Puttin' on the Rap". Los Angeles Times: 63. February 7, 1988.

- ^ a b c d Coleman (2007), p. 352.

- ^ Prince Paul (December 10, 2021). "Public Enemy's It Takes a Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back with Chuck D and Harry Allen". spotify.com (Podcast). Spotify. Event occurs at 2:53. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Myrie (2008), p. 102.

- ^ a b Myrie (2008), p. 106.

- ^ a b Mojo, #21, August 1995

- ^ a b Stacey, Ringo P. "The Quietus : Features : Public Enemy – Chuck D Interview". The Quietus. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ^ Myrie (2008), p. 101.

- ^ a b c d e Coleman (2007), p. 353.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Charnas, Dan. "Respect : Making Noise". Scratch (July/August 2005): pg. 120.

- ^ a b Hinckley, David (February 25, 2005). "The Birth of a 'Nation'". Daily News. New York.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Myrie (2008), pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Myrie (2008), p. 104.

- ^ a b c Eglash (2004), p. 130.

- ^ Christgau, Robert. "Consumer Guide: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". The Village Voice: September 27, 1988. Archived from the original on 2009-12-06. Note: Christgau revised original rating of (A) to (A+).

- ^ a b Shapiro, pp. 304–306

- ^ Hess, Mickey, 2007, Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 176.

- ^ Mark Dery et al. Forman & Neal (2004), p. 484.

- ^ McLeod, Kembrew. "Interview with Chuck D & Hank Shocklee of Public Enemy". Stay Free!. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- ^ a b c d Eglash (2004), p. 131.

- ^ Yauch, Adam (2004). 100 Greatest Artists: Public Enemy | Rolling Stone Music | Lists. Rolling Stone. Retrieved on 2011-03-07.

- ^ Coleman (2007), p. 360.

- ^ a b Myrie (2008), p. 109.

- ^ "Public Enemy: Attacking the Big Bad Monster". The Charlatan. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Hip-Hop's Greatest Year: Fifteen Albums That Made Rap Explode". Rolling Stone. 2008-02-12. Archived from the original on 2018-07-01. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- ^ Columnist. "Trio's Reunion Could Open Many Doors Archived 2012-07-24 at the Wayback Machine". Orlando Sentinel: August 21, 1988.

- ^ "allmusic ((( It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums )))". Allmusic. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ "Public Enemy Album & Song Chart History". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ Gold & Platinum: Searchable Database Archived 2007-06-26 at the Wayback Machine. Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Retrieved on 2009-12-06.

- ^ Concepcion, Mariel (March 13, 2010). 20 Years of Public Enemy's 'Fear Of A Black Planet'. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ Fricke, David (December 15–29, 1988). "Public Enemy: It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back". Rolling Stone. No. 541–542. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert. $25 Guide: The Hottest Sizzlers of Summer. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on December 6, 2009.

- ^ Brown, James (July 9, 1988). "Above the Lore". NME. p. 32.

- ^ Sinclair, David (August 1988). "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". Q. No. 23.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (July 24, 1988). "Public Enemy: Rap With a Fist in the Air". The New York Times. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- ^ Jenkins, Mark. "Review: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". The Washington Post: d.07. July 6, 1988. (Transcription of original review at talk page)

- ^ Columnist. "Review: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". Los Angeles Daily News: September 2, 1988.

- ^ Q, January 1989

- ^ Pazz & Jop 1988: Critics Poll. The Village Voice. Retrieved on December 6, 2009.

- ^ Pazz & Jop 1988: Dean's List. The Village Voice. Retrieved on December 6, 2009.

- ^ Christgau, Robert. "Dancing on a Logjam: Singles Rool in a World Up for Grabs". The Village Voice: February 28, 1989 . .

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back – Public Enemy". AllMusic. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1990). "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". Christgau's Record Guide: The '80s. Pantheon Books. p. 328. ISBN 0-679-73015-X. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- ^ Wazir, Burhan (July 21, 1995). "Public Enemy: Yo! Bum Rush the Show / It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back / Fear of a Black Planet / Apocalypse 91.... The Enemy Strikes Black / Greatest Misses (Island/Def Jam)". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". NME. July 15, 1995. p. 47.

- ^ Jenkins, Craig (November 25, 2014). "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back / Fear of a Black Planet". Pitchfork. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ a b "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". Q. No. 108. September 1995. p. 132.

- ^ Relic, Peter (2004). "Public Enemy". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 661–662. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Grundy, Gareth (June 2000). "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". Select. No. 120. p. 116.

- ^ "Got Five On It". The Source. No. 150. March 2002. pp. 174–179.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric (1995). "Public Enemy". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. pp. 314–315. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- ^ Bennun, David (July 22, 1995). "Public Enemy: Yo! Bum Rush the Show / It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back / Fear of a Black Planet / Apocalypse 91... The Enemy Strikes Black / Greatest Misses". Melody Maker. p. 35.

- ^ Hip Hop Connection, #65, July 1994

- ^ Fletcher, Mansel (March 2000). "100 Best Albums Ever". Hip Hop Connection: 37.

- ^ Chapman, Rob (June 2000). "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". Mojo. No. 79. pp. 124–125.

- ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time : Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. November 18, 2003. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Light, Alan (27 January 2010). "Is Kind of Blue one of the All-TIME 100 Best Albums?". Time.

- ^ Alexander, Phil. "KURT COBAIN'S 50 FAVOURITE ALBUMS". Kerrang!. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ Q August 2006, Issue 241

- ^ Staff (March 5, 2012). "The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s – Feature – Slant Magazine". Slant Magazine. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Spex (1999–2000) Die 100 Alben des Jahrhunderts – Kritiker–Rock Pop Musik Bestenlisten".

- ^ Stacey, Ringo P. "The Quietus : Features : Public Enemy – Chuck D Interview". The Quietus. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ Blender, January/February 2005

- ^ Shepherd, Julianne Escobedo (August 7, 2013). "Kathleen Hanna: Love Among the Ruin". Spin. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Batey, Angus (October 2009). "My record collection – Busta Rhymes". Q. p. 46.

- ^ Metro, May 2009, precise date unknown

- ^ "Eggman – Beastie Boys' Paul's Boutique Samples and References List". PaulsBoutique.info. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ "The Game – Doctor's Advocate (The Samples) – Hip Hop Is Read". HipHopIsRead.com. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ Coleman, Brian. Check The Technique: Liner Notes For Hip-Hop Junkies. New York: Villard/Random House, 2007.

- ^ Adaso, Henry. 100 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums Archived 2015-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. About.com. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ Adaso, Henry. 10 Essential Hip-Hop Albums Archived 2011-01-15 at the Wayback Machine. About.com. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ MacDonald, Bruno (2011). Dimery, Robert (ed.). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. London: Cassell Illustrated. p. 604. ISBN 9781844038909.

- ^ Moon, Tom. 1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die Archived 2012-07-19 at archive.today. Tom Moon. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig, eds. (1995). "Top 100 Alternative Albums". Spin Alternative Record Guide. New York: Vintage Books. p. 453. ISBN 0679755748.

- ^ "allmusic ((( It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back > Credits )))". Allmusic. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ Dutchcharts.nl – Public Enemy – It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back(In Dutch). MegaCharts Album Top 100. Hung Medien / hitparade.ch. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ "everyHit.com – UK Top 40 Chart Archive, British Singles & Album Charts – Format Search: Albums – Artist Search: Public Enemy". everyHit.com. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "British album certifications – Public Enemy – It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "American album certifications – Public Enemy – It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Bibliography

- Ron Eglash (2004). Appropriating Technology: Vernacular Science and Social Power. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3427-9.

- Brian Coleman (2007). Check the Technique: Liner Notes for Hip-Hop Junkies. Villard Books. ISBN 978-0-8129-7775-2.

- Russell Myrie (2008). Don't Rhyme For the Sake of Riddlin': The Authorized Story of Public Enemy. Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84767-182-0.

- Nathan Brackett, Christian Hoard (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide: Completely Revised and Updated 4th Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Peter Shapiro (2005). Rough Guide to Hip Hop. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-263-7.

- Murray, Forman; Neal, Mark Anthony, eds. (2004). That's the Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96919-0.

- Strong, Martin Charles (October 21, 2004). The Great Rock Discography (7th ed.). Canongate U.S. ISBN 1-84195-615-5.

External links

[edit]- It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (Adobe Flash) at Radio3Net (streamed copy where licensed)

- It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back at Discogs (list of releases)

- It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back Archived 2012-10-23 at the Wayback Machine at Pitchfork Media