David Dinkins

David Dinkins | |

|---|---|

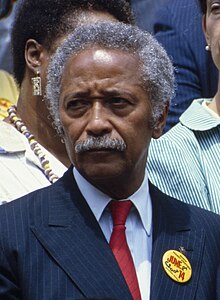

Dinkins in 1986 | |

| 106th Mayor of New York City | |

| In office January 1, 1990 – December 31, 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Ed Koch |

| Succeeded by | Rudy Giuliani |

| 23rd Borough President of Manhattan | |

| In office January 1, 1986 – December 31, 1989 | |

| Preceded by | Andrew Stein |

| Succeeded by | Ruth Messinger |

| Member of the New York State Assembly from the 78th district | |

| In office January 1, 1966 – December 31, 1966 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Edward A. Stevenson Sr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | David Norman Dinkins July 10, 1927 Trenton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | November 23, 2020 (aged 93) New York City, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations | Democratic Socialists of America |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Howard University (BS) Brooklyn Law School (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1945–1946 |

David Norman Dinkins (July 10, 1927 – November 23, 2020) was an American politician, lawyer, and author who served as the 106th mayor of New York City from 1990 to 1993.

Dinkins was among the more than 20,000 Montford Point Marines, the first African-American U.S. Marines, from 1945 to 1946.[1] He graduated cum laude from Howard University and received his law degree from Brooklyn Law School in 1956. A longtime member of Harlem's Carver Democratic Club, Dinkins began his electoral career by serving in the New York State Assembly in 1966, eventually advancing to Manhattan borough president.[2] He won the 1989 New York City mayoral election, becoming the first African American to hold the office. After losing re-election in 1993, Dinkins joined the faculty of Columbia University while remaining active in municipal politics.

Early life and education

[edit]Dinkins was born in Trenton, New Jersey, to Sarah "Sally" Lucy Dinkins, a domestic worker, and William Harvey Dinkins Jr., a barber and real estate agent.[3][4] His parents separated when he was six years old, after which he was raised by his father.[4] Dinkins moved to Harlem as a child before returning to Trenton. He attended Trenton Central High School, where he graduated in 1945.[5]

Upon graduating, Dinkins attempted to enlist in the United States Marine Corps but was told that a racial quota had been filled. After traveling the Northeastern United States, he finally found a recruiting station that had not, in his words, "filled their quota for Negro Marines"; however, World War II was over before Dinkins finished boot camp.[6] He served in the Marine Corps from July 1945 through August 1946, attaining the rank of private first class.[7][8][9] Dinkins was among the Montford Point Marines who received the Congressional Gold Medal from the United States Senate and House of Representatives.[6]

Dinkins graduated cum laude from Howard University[3] with a bachelor's degree in mathematics in 1950. He received his LL.B. from Brooklyn Law School in 1956.[9][10]

Political career

[edit]Early and middle career

[edit]While maintaining a private law practice from 1956 to 1975, Dinkins rose through the Democratic Party organization in Harlem, beginning at the Carver Democratic Club under the aegis of J. Raymond Jones.[3][11] He became part of an influential group of African American politicians that included Denny Farrell, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, and Charles Rangel; the latter three together with Dinkins were known as the "Gang of Four".[12] As an investor, Dinkins was one of fifty African American investors who helped Sutton found Inner City Broadcasting Corporation in 1971.[13]

Dinkins briefly represented the 78th District of the New York State Assembly in 1966. From 1972 to 1973, he was president of the New York City Board of Elections. In late 1973, he was poised to take office as New York City's first Black deputy mayor in the administration of Mayor-elect Abraham D. Beame; however, the appointment was not effectuated amid "difficulties that stemmed from [Dinkins'] failure to pay federal, state or city personal income taxes for four years."[14][15] Instead, he served as city clerk (characterized by Robert D. McFadden as a "patronage appointee who kept marriage licenses and municipal records") from 1975 to 1985.[16][17] He was elected Manhattan borough president in 1985 on his third run for that office. On November 7, 1989, Dinkins was elected mayor of New York City, defeating three-term incumbent mayor Ed Koch and two others in the Democratic primary and Republican nominee Rudy Giuliani in the general election. During his campaign, Dinkins sought the blessing and endorsement of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe.[18]

Dinkins was elected in the wake of a corruption scandal that stemmed from the decline of longtime Brooklyn Democratic Party chairman and preeminent New York City political leader Meade Esposito's American Mafia-influenced patronage network, ultimately precipitating the suicide of Queens Borough President Donald Manes and a series of criminal convictions among the city's Democratic leadership. In March 1989, the New York City Board of Estimate (which served as the primary governing instrument of various patronage networks for decades, often superseding the mayoralty in influence) also was declared unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause by the Supreme Court of the United States; this prompted the empanelment of the New York City Charter Revision Commission, which abolished the Board of Estimate and assigned most of its responsibilities to an enlarged New York City Council via a successful referendum in November. Koch, the presumptive Democratic nominee, was politically damaged by his administration's ties to the Esposito network and his handling of racial issues, exemplified by his fealty to affluent interests in predominantly white areas of Manhattan. This enabled Dinkins to attenuate public perceptions of his previous patronage appointments and emerge as a formidable, reform-minded challenger to Koch.[19] Additionally, the fact that Dinkins was African American helped him to avoid criticism that he was ignoring the Black vote by campaigning to whites.[20] While a large turnout of African American voters was important to his election, Dinkins campaigned throughout the city.[3] Dinkins' campaign manager was political consultant William Lynch Jr., who became one of his first deputy mayors.[21]

Mayoralty

[edit]Crime

[edit]

Dinkins entered office in January 1990 pledging racial healing, and famously referred to New York City's demographic diversity as "not a melting pot, but a gorgeous mosaic".[22] The crime rate in New York City had risen alarmingly during the 1980s, and the rate of homicide in particular reached an all-time high of 2,245 cases during 1990, the first year of the Dinkins administration.[23] The rates of most crimes, including all categories of violent crime, then declined during the remainder of his four-year term. That ended a 30-year upward spiral and initiated a trend of falling rates that continued and accelerated beyond his term.[24][25] However, the high absolute levels, the peak early in his administration, and the only modest decline subsequently (homicide down 12% from 1990 to 1993)[26] resulted in Dinkins' suffering politically from the perception that crime remained out of control on his watch.[27][28] Dinkins in fact initiated a hiring program that expanded the police department nearly 25%. The New York Times reported, "He obtained the State Legislature's permission to dedicate a tax to hire thousands of police officers, and he fought to preserve a portion of that anticrime money to keep schools open into the evening, an award-winning initiative that kept tens of thousands of teenagers off the street."[28][29]

Dinkins' term was marked by a greater push toward accountability and oversight regarding police misconduct, which led to friction between Dinkins and the city's Patrolmen's Benevolent Association (PBA). In 1992, Dinkins proposed a bill to change the leadership of the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB), the oversight body that examined complaints of police misconduct, from half-cop–half-civilian to all civilian and make it independent of the New York Police Department.[30] Following the Washington Heights Riot, fueled by the beating of Jose "Kiko" Garcia, an undocumented Dominican Republic immigrant, by a police officer, Dinkins attempted to diffuse tensions by inviting Garcia's family to Gracie Mansion. This gesture outraged the city's PBA, who claimed Dinkins's actions showed favoritism toward Garcia and bias against the police.[31] To condemn Dinkins' position on policing, the city PBA organized a protest on September 16, 1992, which quickly turned violent when nearly 4,000 off-duty police officers blocked traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge and knocked over police barricades in an attempt to rush City Hall.[32] The nearly 300 uniformed on-duty officers did little to control the riot.[33][34][35] Despite the riot and objections from the PBA, the CCRB was reorganized and made independent from the police department in July 1993.[36]

Dealmaking

[edit]Dinkins was rebuffed in his attempt to end the licensing of locksmiths.[37][38]

During his final days in office, Dinkins made last-minute negotiations with the sanitation workers, presumably to preserve the public status of garbage removal. Giuliani, who had defeated Dinkins in the 1993 mayoral race, blamed Dinkins for a "cheap political trick" when Dinkins planned the resignation of Victor Gotbaum, Dinkins' appointee on the board of education, thus guaranteeing Gotbaum's replacement six months in office.[39] Dinkins also signed a last-minute 99-year lease with the USTA National Tennis Center. By negotiating a fee for New York City based on the event's gross income, the Dinkins administration made a deal with the US Open that brings more economic benefit to the City of New York each year than the New York Yankees, New York Mets, New York Knicks, and New York Rangers combined.[3] The city's revenue-producing events Fashion Week, Restaurant Week, and Broadway on Broadway were all created under Dinkins.[40]

Other longterm matters

[edit]Dinkins's term was marked by polarizing events such as the Family Red Apple boycott, a boycott of a Korean-owned grocery in Flatbush, Brooklyn, and the 1991 Crown Heights riot. When Lemrick Nelson was acquitted of murdering Yankel Rosenbaum during the Crown Heights riots, Dinkins said, "I have no doubt that in this case the criminal-justice system has operated fairly and openly."[41] Later he wrote in his memoirs, "I continue to fail to understand that verdict."[3]

In 1991, when "Iraqi Scud missiles were falling" in Israel[42] and the Mayor's press secretary said "security would be tight and gas masks would be provided for the contingent",[43] Mayor Dinkins visited Israel as a sign of support.[44]

The Dinkins administration was adversely affected by a declining economy, which led to lower tax revenue and budget shortfalls.[45] Nevertheless, Dinkins' mayoralty was marked by a number of significant achievements.[45] New York City's crime rate, including the murder rate, declined in Dinkins' final years in office; Dinkins persuaded the state legislature to dedicate certain tax revenue for crime control (including an increase in the size of the New York Police Department along with after-school programs for teenagers), and he hired Raymond W. Kelly as police commissioner.[45] Times Square was cleaned up during Dinkins' term, and he persuaded The Walt Disney Company to rehabilitate the old New Amsterdam Theatre on 42nd Street.[45] The city negotiated a 99-year lease of city park space to the United States Tennis Association to create the USTA National Tennis Center (which Mayor Michael Bloomberg later called "the only good athletic sports stadium deal, not just in New York, but in the country").[45] Dinkins continued an initiative begun by Ed Koch to rehabilitate dilapidated housing in northern Harlem, the South Bronx, and Brooklyn; overall more housing was rehabilitated in Dinkins' only term than Giuliani's two terms.[45] With the support of Governor Mario Cuomo, the city invested in supportive housing for mentally ill homeless people and achieved a decrease in the size of the city's homeless shelter population to its lowest point in two decades.[28]

1993 election

[edit]In 1993, Dinkins lost to Republican Rudy Giuliani in a rematch of the 1989 election. Dinkins earned 48.3 percent of the vote, down from 51 percent in 1989.[46] One factor in his loss was his perceived indifference to the plight of the Jewish community during the Crown Heights riot.[47] Another was a strong turnout for Giuliani in Staten Island; a referendum on Staten Island's secession from New York was placed on the ballot that year by Democratic Governor Mario Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.[3]

Later career

[edit]

From 1994 until his death, Dinkins was a professor of professional practice at the Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs.[48]

Dinkins was a member of the board of directors of the United States Tennis Association.[49] He served on the boards of the New York City Global Partners, the Children's Health Fund, the Association to Benefit Children, and the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund. Dinkins was also on the advisory board of Independent News & Media and the Black Leadership Forum, was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, and served as chairman emeritus of the board of directors of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS.[50]

Dinkins' radio program Dialogue with Dinkins aired on WLIB radio in New York City from 1994 to 2014.[51][52] His memoirs, A Mayor's Life: Governing New York's Gorgeous Mosaic,[3] written with Peter Knobler, were published in 2013.[53][54]

Although he never attempted a political comeback, Dinkins remained somewhat active in politics after his mayorship, and his endorsements of various candidates, including Mark Green in the 2001 mayoral race, were well-publicized. He supported Democrats Fernando Ferrer in the 2005 New York mayoral election, Bill Thompson in 2009, and Bill de Blasio in 2013.[55][56] During the 2004 Democratic presidential primaries, Dinkins endorsed and actively campaigned for Wesley Clark.[57] In the campaign for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination, Dinkins served as an elected delegate from New York for Hillary Clinton.[58] During the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries, Dinkins endorsed former Mayor Michael Bloomberg for president on February 25, 2020, just before a Democratic debate.[59]

Dinkins sat on the board of directors and in 2013 was on the Honorary Founders Board of The Jazz Foundation of America.[60][61] He worked with that organization to save the homes and lives of America's elderly jazz and blues musicians, including musicians who survived Hurricane Katrina. He served on the boards of the Children's Health Fund (CHF), the Association to Benefit Children, and the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund (NMCF). Dinkins was also chairman emeritus of the board of directors of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS.[50] He was a champion of college access, serving on the Posse Foundation National Board of Directors until his death in 2020.[62]

The David N. Dinkins Municipal Building in Manhattan was named after the former mayor in 2015 by mayor Bill de Blasio.[63]

Personal life

[edit]

Dinkins married Joyce Burrows, the daughter of Harlem political eminence Daniel L. Burrows, in August 1953.[64][65] They had two children, David Jr. and Donna.[66] When Dinkins became mayor of New York City, Joyce retired from her position at the State Department of Taxation and Finance. The couple were members of the Church of the Intercession in New York City. Joyce died on October 11, 2020, at the age of 89.[67]

Dinkins was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha and Sigma Pi Phi ("the Boule"), the oldest collegiate and first professional Greek-letter fraternities, respectively, established for African Americans. He was raised as a Master Mason in King David Lodge No. 15, F. & A. M., PHA, located in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1952.[68]

In 1994, Dinkins was part of an Episcopal Church delegation to Haiti.[69]

Dinkins was hospitalized in New York on October 31, 2013, for treatment of pneumonia.[70] He was hospitalized again for pneumonia on February 19, 2016.[71]

Dinkins starred as himself on April 13, 2018, in "Risk Management", the 19th episode of the 8th season of the CBS police procedural drama Blue Bloods.[72]

Death

[edit]On November 23, 2020, Dinkins died from unspecified natural causes at his home on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, about a month after his wife's death. He was 93.[66][73]

Books

[edit]- Dinkins, David N.; Knobler, Peter (2013). A Mayor's Life: Governing New York's Gorgeous Mosaic. New York: PublicAffairs Books. ISBN 9781610393010. OCLC 826322884.

See also

[edit]- List of mayors of New York City

- Timeline of New York City, 1980s–1990s

References

[edit]- ^ Dinkins, David (July 21, 2005). "Transcript of Interview with Dinkins, David". library.uncw.edu.

- ^ "Dinkins Seriously Considers Entering the Race for Mayor" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Lynn, Frank, The New York Times, December 8, 1988.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dinkins, David N.; Knobler, Peter (2013). A Mayor's Life: Governing New York's Gorgeous Mosaic. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-301-0.

- ^ a b McQuiston, John T. (October 20, 1991). "William Dinkins, Mayor's Father And Real Estate Agent, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Abdur-Rahman, Sulaiman (November 24, 2020). "Legendary city native David Dinkins dies at 93". The Trentonian. Retrieved November 25, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Hockenberry, John (June 27, 2012). "First Black Marines Awarded Congressional Gold Medal". The Takeaway. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Marriott, Michel (November 28, 1988). "To Run or Not to Run: Dinkins's Struggle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ "David Dinkins Biography – 1190 WLIB – Your Praise & Inspiration Station". Wlib.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Cheers, D. Michael. "Mayor of 'The Big Apple': 'nice guy' image helps David N. Dinkins in building multi-ethnic, multiracial coalition – New York City" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Ebony (magazine), February 1990. Accessed September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Marquis Biographies Online". Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "J. Raymond Jones, Harlem Kingmaker, Dies at 91" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Fraser, C. Gerald, The New York Times, June 11, 1991.

- ^ Schapiro, Rich, "Harlem 'trailblazer', former World War II Tuskegee Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Airmen [sic] Percy Sutton dies", New York Daily News, December 27, 2009.

- ^ "David Dinkins, New York's First and Only Black Mayor, Dies at 93". Archived from the original on December 28, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Schumach, Murray (December 29, 1973). "Dinkins Pulls Out as Aide to Beame; Failed to Pay Tax". The New York Times.

- ^ Boyd, Herb; Arinde, Nayaba (November 24, 2020). "David N. Dinkins, the first Black mayor of New York City, dead at 93". St. Louis American.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (November 24, 2020). "David N. Dinkins, New York's First Black Mayor, Dies at 93". The New York Times.

- ^ "NYC 100 – NYC Mayors – The First 100 Years". Nyc.gov. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ Ehrlich, M. Avrum, The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present (KTAV Publishing, January 2005), p. 109. ISBN 0-88125-836-9

- ^ Lankevich, George J. (2002). New York City: A Short History. NYU Press. pp. 237–238, paragraph 3. ISBN 9780814751862. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ Thompson, J. Phillip, "David Dinkins' Victory in New York City: The Decline of the Democratic Party Organization and the Strengthening of Black Politics" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Political Science & Politics via jstor.org, June 1990.

- ^ Katz, Celeste (August 9, 2013). "Political consultant William Lynch Jr. dies at 72". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Purdum, Todd S. (January 2, 1990). "Mayor Dinkins; Dinkins Sworn In; Stresses Aid to Youth". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ The Power of the Mayor, Chris McNickle, p. 355

- ^ Dinkins, David N.; Knobler, Peter (2013). A Mayor's Life: Governing New York's Gorgeous Mosaic. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-301-0. Riggio, Len, Foreword, page xi.

- ^ Langan, Patrick A.; Matthew R. Durose (December 2003). "The Remarkable Drop in Crime in New York City". In Linda Laura Sabbadini; Maria Giuseppina Muratore; Giovanna Tagliacozzo (eds.). Towards a Safer Society: The Knowledge Contribution of Statistical Information (PDF). Rome: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (published 2009). pp. 131–174. ISBN 978-88-458-1640-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

According to NYPD statistical analysis, crime in New York City took a downturn starting around 1990 that continued for many years, shattering all the city's old records for consecutive-year declines in crime rates. [See also Appendix: Tables 1–2.]

- ^ The Power of the Mayor, Chris McNickle, p. 356

- ^ Barrett, Wayne (June 25, 2001). "Giuliani's Legacy: Taking Credit For Things He Didn't Do". Gotham Gazette. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c Powell, Michael (October 25, 2009). "Another Look at the Dinkins Administration, and Not by Giuliani". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (August 7, 1994). "As Police Force Adds to Ranks, Some Promises Still Unfulfilled". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ Nahmias, Laura (October 4, 2021). "White Riot In 1992, thousands of furious, drunken cops descended on City Hall — and changed New York history". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Finder, Alan (September 11, 1992). "The Washington Heights Case; In Washington Heights, Dinkins Defends Actions After Shooting". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Oliver, Pamela (July 18, 2020). "When the NYPD Rioted – Race, Politics, Justice". Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Voorhees, Josh (December 22, 2014). "Déjà Blue". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ Manegold, Catherine S. (September 27, 1992). "Rally Puts Police Under New Scrutiny". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Mckinley, James C. Jr. (September 17, 1992). "Officers Rally And Dinkins Is Their Target". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ "Shielded from Justice: New York: Civilian Complaint Review Board". www.hrw.org. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Rebuffed by NYC City Council via a technicality David Seifman (July 3, 1992). "Dave gives some business license to skip license". New York Post. p. 8.

the Council's Consumer Affairs Committee failed to muster a quorum

- ^ New York City and Miami have their own licensing laws. "States with Locksmith Laws". February 7, 2018.

- ^ Siegel, Fred, The Prince of the City: Giuliani, New York, and the Genius of American Life (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2005), p. 90.

- ^ Nesoff, Bob. "David Dinkins! New York Now and Then". New York Lifestyles Magazine. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Taylor, John (December 7, 1992). "The Politics of Grievance: Dinkins, the Blacks, and the Jews". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ Clyde Haberman (July 9, 1993). "Dinkins Leaves Israel". The New York Times. p. B3.

- ^ Felicia R. Lee (January 26, 1991). "Dinkins to Lead Contingent in Trip to Israel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Jonathan Ferziger (February 4, 1991). "Dinkins visits Shamir, Patriots, Ethiopians". UPI.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Powell, Michael (October 5, 2009). "Another Look at the Dinkins Administration, and Not by Giuliani". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Purdum, Todd S. (November 3, 1993). "Giuliani ousts Dinkins by a thin margin ..." The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Shapiro, Edward S. (2006). Crown Heights: Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Riot. Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, University Press of New England. ISBN 1-58465-561-5. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ "SIPA: Faculty David N. Dinkins". Columbia University. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan". Tennis.com.

- ^ a b "David N. Dinkins, Director at Large". United States Tennis Association. Archived from the original on July 20, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ "Praise Team: On-Air Schedule". WLIB. January 6, 2009. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007.

- ^ Hinckley, David (April 4, 2014). "After two decades, David Dinkins signing off at radio station WLIB". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Trentonian David Dinkins tells all in A Mayor's Life" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Trenton (NJ) Trentonian, September 21, 2013.

- ^ "Their Honors" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Roberts, Sam, The New York Times, Sunday Book Review, November 22, 2013.

- ^ "William Thompson picks up a pair of key endorsements" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Fermino, Jennifer, Daily News (New York), June 3, 2013.

- ^ "The Ghosts of Mayors Past" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Roberts, Sam, The New York Times, September 29, 2013.

- ^ "David Dinkins supports Wesley Clark, to join him in N.H." Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, USA Today, Associated Press, January 21, 2004.

- ^ "Reporters Notebook: New Yorkers make their mark on Maryland politics". The Gazette. Gaithersburg, MD. October 1, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ Wilkinson, Joseph (February 25, 2020). "Former NYC Mayor David Dinkins endorses Mike Bloomberg for President". nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "Hon. David Dinkins" Archived March 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, JazzFoundation.org. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ McMullan, Patrick, May 10, 2009. "The Jazz Foundation of America's 'A great night in Harlem' benefit" (photo archive) Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine patrickmcmullan.com, May 29, 2008. Event at the Apollo Theater, NYC. Accessed: May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Longtime Board Member, Former NYC Mayor David Dinkins Reflects on Path to Education, Posse" Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, possefoundation.org. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Hajela, Deepti (November 24, 2020). "David Dinkins, first Black mayor of New York City, dies at 93". Global News. Associated Press. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ "Joyce Burrows and David Dinkins are wed in double ring ceremony". The New York Age. September 5, 1953. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ Marriott, Michel (January 1, 1990). "Joyce Dinkins, a Quiet Lady Who Is No Longer a Private Person". New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ a b McFadden, Robert D. (November 24, 2020). "David N. Dinkins, New York's First Black Mayor, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ "Joyce Dinkins, wife of NYC's first Black mayor, dies". MSN. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ Stieb, Matt (November 24, 2020). "David Dinkins, New York's First and Only Black Mayor, Has Died at 93". Intelligencer.

- ^ Lemonis, Anita (June 15, 1994). "piscopal Church Delegation to Haiti Finds Desperate Struggle to Cope". Episcopal News Service. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ "Dinkins hospitalized". New York: WNYW. October 31, 2013. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013.

- ^ "Former NYC Mayor Dinkins Hospitalized for Pneumonia". ABC News.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ "Listings-Blue Bloods". The Futon Critic. April 13, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ "Former New York City Mayor David Dinkins Dies at 93". NBC 4 New York. November 23, 2020. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- McNickle, Chris (2012). The Power of the Mayor: David Dinkins, 1990–1993. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412849593. OCLC 930793065.

- Paterson, David (2020). Black, Blind, & in Charge: A Story of Visionary Leadership and Overcoming Adversity. New York.

- Rangel, Charles B.; Wynter, Leon (2007). And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- John C. Walker (1989). The Harlem Fox: J. Raymond Jones at Tammany 1920–1970, New York: State University New York Press.

External links

[edit]- 1927 births

- 2020 deaths

- 1992 United States presidential electors

- 20th-century African-American politicians

- 20th-century American politicians

- 21st-century African-American politicians

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American memoirists

- African-American Episcopalians

- African-American mayors in New York (state)

- African-American state legislators in New York (state)

- Brooklyn Law School alumni

- Columbia School of International and Public Affairs faculty

- Columbia University faculty

- David Paterson

- Howard University alumni

- Lawyers from New York City

- Manhattan borough presidents

- Mayors of New York City

- Democratic Party members of the New York State Assembly

- Military personnel from New Jersey

- People from the Upper East Side

- Politicians from Trenton, New Jersey

- Trenton Central High School alumni

- United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II

- United States Marines

- Writers from Manhattan

- Writers from Trenton, New Jersey

- Alpha Phi Alpha members