Sacred bull

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Cattle are prominent in some religions and mythologies. As such, numerous peoples throughout the world have at one point in time honored bulls as sacred. In the Sumerian religion, Marduk is the "bull of Utu". In Hinduism, Shiva's steed is Nandi, the Bull. The sacred bull survives in the constellation Taurus. The bull, whether lunar as in Mesopotamia or solar as in India, is the subject of various other cultural and religious incarnations as well as modern mentions in New Age cultures.

In prehistoric art

[edit]

Aurochs are depicted in many Paleolithic European cave paintings such as those found at Lascaux and Livernon in France. Their life force may have been thought to have magical qualities, for early carvings of the aurochs have also been found. The impressive and dangerous aurochs survived into the Iron Age in Anatolia and the Near East and were worshipped throughout that area as sacred animals; the earliest remnants of bull worship can be found at neolithic Çatalhöyük.

In antiquity

[edit]Mesopotamia

[edit]

The Sumerian guardian deity called lamassu was depicted as hybrids with bodies of either winged bulls or lions and heads of human males. The motif of a winged animal with a human head is common to the Near East, first recorded in Ebla around 3000 BCE. The first distinct lamassu motif appeared in Assyria during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser II as a symbol of power.

"The human-headed winged bulls protective genies called shedu or lamassu, ... were placed as guardians at certain gates or doorways of the city and the palace. Symbols combining man, bull, and bird, they offered protection against enemies."[1]

The bull was also associated with the storm and rain god Adad, Hadad or Iškur. The bull was his symbolic animal. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus; the Roman god Jupiter, as Jupiter Dolichenus; the Indo-European Nasite Hittite storm-god Teshub; the Egyptian god Amun. When Enki distributed the destinies, he made Iškur inspector of the cosmos. In one litany, Iškur is proclaimed again and again as "great radiant bull, your name is heaven" and also called son of Anu, lord of Karkara; twin-brother of Enki, lord of abundance, lord who rides the storm, lion of heaven.

The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh depicts the horrors of the rage-fueled deployment of the Bull of Heaven by Ishtar and its slaughter by Gilgamesh and Enkidu as an act of defiance that seals their fates:

Ishtar opened her mouth and said again, "My father, give me the Bull of Heaven to destroy Gilgamesh. Fill Gilgamesh, I say, with arrogance to his destruction; but if you refuse to give me the Bull of Heaven I will break in the doors of hell and smash the bolts; there will be a confusion of people, those above with those from the lower depths. I shall bring up the dead to eat food like the living; and the hosts of the dead will outnumber the living." Anu said to great Ishtar, "If I do what you desire there will be seven years of drought throughout Uruk when corn will be seedless husks. Have you saved grain enough for the people and grass for the cattle?" Ishtar replied "I have saved grain for the people, grass for the cattle."...When Anu heard what Ishtar had said he gave her the Bull of Heaven to lead by the halter down to Uruk. When they reached the gates of Uruk the Bull of Heaven went to the river; with his first snort cracks opened in the earth and a hundred young men fell down to death. With his second snort cracks opened and two hundred fell down to death. With his third snort cracks opened, Enkidu doubled over but instantly recovered, he dodged aside and leapt onto the Bull and seized it by the horns. The Bull of Heaven foamed in his face, it brushed him with the thick of its tail. Enkidu cried to Gilgamesh, "My friend we boasted that we would leave enduring names behind us. Now thrust your sword between the nape and the horns." So Gilgamesh followed the Bull, he seized the thick of its tail, he thrust the sword between the nape and the horns and slew the Bull. When they had killed the Bull of Heaven they cut out its heart and gave it to Shamash, and the brothers rested.[2]

Egypt

[edit]

In Ancient Egypt multiple sacred bulls were worshiped. A long succession of ritually perfect bulls were identified by the god's priests, housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and buried. The mother-cows of these animals were also revered, and buried in separate locations.[3]

- In the Memphite region, the Apis was seen as the embodiment of Ptah and later of Osiris. Some of the Apis bulls were buried in large sarcophagi in the underground vaults of the Serapeum of Saqqara, which was rediscovered by Auguste Mariette in 1851.[3]

- Mnevis of Heliopolis was the embodiment of Atum-Ra.[3]

- Buchis of Hermonthis was linked with the gods Ra and Montu. The catacombs for these bulls are now known as the Bucheum. Multiple Buchis mummies were found in situ during excavations in the 1930s. Some of their sarcophagi are similar to those in the Serapeum, others are polylithic (made from multiple stones).[3]

Ka, in Egyptian, is both a religious concept of life-force/power and the word for bull.[4] Andrew Gordon, an Egyptologist, and Calvin Schwabe, a veterinarian, argue that the origin of the ankh is related to two other signs of uncertain origin that often appear alongside it: the was-sceptre, representing "power" or "dominion", and the djed pillar, representing "stability". According to this hypothesis, the form of each sign is drawn from a part of the anatomy of a bull, like some other hieroglyphic signs that are known to be based on body parts of animals. In Egyptian belief semen was connected with life and, to some extent, with "power" or "dominion", and some texts indicate the Egyptians believed semen originated in the bones. Therefore, Calvin and Schwabe suggest the signs are based on parts of the bull's anatomy through which semen was thought to pass: the ankh is a thoracic vertebra, the djed is the sacrum and lumbar vertebrae, and the was is the dried penis of the bull.[5]

Central Anatolia

[edit]

We cannot recreate a specific context for the bull skulls with horns (bucrania) preserved in an 8th millennium BCE sanctuary at Çatalhöyük in Central Anatolia. The sacred bull of the Hattians, whose elaborate standards were found at Alaca Höyük alongside those of the sacred stag, survived in Hurrian and Hittite mythology as Seri and Hurri ("Day" and "Night"), the bulls who carried the weather god Teshub on their backs or in his chariot and grazed on the ruins of cities.[6]

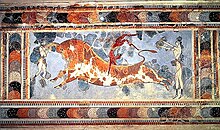

Crete

[edit]

Bulls were a central theme in the Minoan civilization, with bull heads and bull horns used as symbols in the Knossos palace. Minoan frescos and ceramics depict bull-leaping, in which participants of both sexes vaulted over bulls by grasping their horns.

Iran

[edit]

The Iranian language texts and traditions of Zoroastrianism have several different mythological bovine creatures. One of these is Gavaevodata, which is the Avestan name of a hermaphroditic "uniquely created (-aevo.data) cow (gav-)", one of Ahura Mazda's six primordial material creations that becomes the mythological progenitor of all beneficent animal life. Another Zoroastrian mythological bovine is Hadhayans, a gigantic bull so large that it could straddle the mountains and seas that divide the seven regions of the earth, and on whose back men could travel from one region to another. In medieval times, Hadhayans also came to be known as Srīsōk (Avestan *Thrisaok, "three burning places"), which derives from a legend in which three "Great Fires" were collected on the creature's back. Yet another mythological bovine is that of the unnamed creature in the Cow's Lament, an allegorical hymn attributed to Zoroaster himself, in which the soul of a bovine (geush urvan) despairs over her lack of protection from an adequate herdsman. In the allegory, the cow represents humanity's lack of moral guidance, but in later Zoroastrianism, Geush Urvan became a yazata representing cattle. The 14th day of the month is named after her and is under her protection.

South Asia and South East Asia

[edit]The Indian Subcontinent

[edit]

Bulls appear on seals from the Indus Valley civilisation.

Vedic period

[edit]In The Rig Veda, the earliest collection of Vedic hymns (c. 1500-1000 BCE), Indra is often praised as a Bull (Vṛṣabha – vrsa (he) plus bha (being) or as uksan, a bull aged five to nine years, which is still growing or just reached its full growth). The bull is an icon of power and virile strength in Aryan literature and other Indo-European traditions.[7] Vrsha means "to shower or to spray", in this context Indra showers strength and virility. Vṛṣabha is also an astrological sign in Indian horoscope systems, corresponding to Taurus

The storm god Rudra is called a bull as are the Maruts or storm deities referred to as bulls under the command of Indra, thus Indra is called "bull with bulls." The following excerpts from The Rig Veda demonstrate these attributes:

"As a bull I call to you, the bull with the thunderbolt, with various aids, O Indra, bull with bulls, greatest killer of Vrtra." — Atri and the Last Sun

"He the mighty bull who with his seven reins let loose the seven rivers to flow, who with his thunderbolt in his hand hurled down Ruhina as he was climbing up to the sky, he my people is Indra." — Who is Indra?

"I send praise to the high bull, tawny and white. I bow low to the radiant one. We praise the dreaded name of Rudra." — Rudra, father of the Maruts.[8]

Nandi later appears in the Puranas as the primary vahana (mount) and the principal gana (follower) of Shiva. Nandi figures depicted as a seated bull are present at Shiva temples throughout the world.

Coinage

[edit]

The humpbacked Zebu bull (bos indicus) appears on the coinage of the Indian subcontinent from the Iron Age to the modern day. Bull symbols appear regularly on silver karshapana, or punchmarked coins, first issued by the Janapada kingdoms, and continued by the Magadhan and Mauryan empires. In additional to the bull, many karshapana contain taurine symbols of the mark left by the bulls hoof, also referred to as a nandipada (Nandi's foot) symbol which appears in Vedic, Hindu, Jain and Iranic iconography.[9]

Kushan empire (c.30-275 CE) coins and those of the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom (230-365) depict the Iranian god Wēś beside a bull, sometimes holding a trident and beside a Nandipada symbol.[10]

The silver "bull and horseman" Jital of the Kabul or Hindu Shahi (850-1000) depicts a recumbent bull with a trishula on rump and the Nāgarī script legend above: "Sri Samanta Deva (Radiant Samanta the God). This design was copied by later Rajput dynasties including the Tomaras of Delhi, the Chauhan dynasty and the Rathore dynasty on copper and billon (alloy) coins.[11]

Upon independence from colonial rule, the bull reappeared in modern coins of the Indian rupee on the reverse of the 2 Anna coin in 1950.

Meitei mythology

[edit]

Kao (bull), a supernatural divine bull, appears in ancient Meitei mythology and folklore of Ancient Manipur (Kangleipak). In the legend of the Khamba Thoibi epic, Nongban Kongyamba, a nobleman of ancient Moirang realm, pretended to be an oracle and falsely prophesied that the people of Moirang would lead to miserable lives, if the powerful Kao (bull) roaming freely in the Khuman kingdom, wasn't offered to God Thangjing (Old Manipuri: Thangching), the presiding deity of Moirang. Orphan Khuman prince Khamba was chosen to capture the bull, as he was known for his valor and faithfulness. Since to capture the bull without killing it was not an easy task, Khamba's motherly sister Khamnu disclosed to Khamba the secrets of the bull, with which the bull was able to get captured.[12][13][14]

Cyprus

[edit]In Cyprus, bull masks made from real skulls were worn in rites[example needed]. Bull-masked terracotta figurines[15] and Neolithic bull-horned stone altars have been found in Cyprus.

Levant

[edit]

Bull figurines are common finds on archaeological sites across the Levant;[citation needed] two examples are the 16th century BCE (Middle Bronze Age) bull calf from Ashkelon,[16] and the 12th century BCE (Iron Age I) bull found at the so-called Bull Site in Samaria on the West Bank.[17] Both Baʿal and El were associated with the bull in Ugaritic texts, as it symbolized both strength and fertility.[18]

Exodus 32:4[19] reads "He took this from their hand, and fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a molten calf; and they said, 'This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt'."

Nehemiah 9:18[20] reads "even when they made an idol shaped like a calf and said, 'This is your god who brought you out of Egypt!' They committed terrible blasphemies."

Calf-idols are referred to later in the Tanakh, such as in the Book of Hosea,[21] which would seem accurate as they were a fixture of near-eastern cultures.[citation needed]

Solomon's "Molten Sea" basin stood on twelve brazen bulls.[22][23]

Young bulls were set as frontier markers at Dan and Bethel, the frontiers of the Kingdom of Israel.[citation needed]

Much later, in Abrahamic religions, the bull motif became a bull demon or the "horned devil" in contrast and conflict to earlier traditions. The bull is familiar in Judeo-Christian cultures from the Biblical episode wherein an idol of the golden calf (Hebrew: עֵגֶּל הַזָהָב) is made by Aaron and worshipped by the Hebrews in the wilderness of the Sinai Peninsula (Book of Exodus). The text of the Hebrew Bible can be understood to refer to the idol as representing a separate god, or as representing Yahweh himself, perhaps through an association or religious syncretism with Egyptian or Levantine bull gods, rather than a new deity in itself.[citation needed]

Greece

[edit]

Among the Twelve Olympians, Hera's epithet Bo-opis is usually translated "ox-eyed" Hera, but the term could just as well apply if the goddess had the head of a cow, and thus the epithet reveals the presence of an earlier, though not necessarily more primitive, iconic view. (Heinrich Schlieman, 1976) Classical Greeks never otherwise referred to Hera simply as the cow, though her priestess Io was so literally a heifer that she was stung by a gadfly, and it was in the form of a heifer that Zeus coupled with her. Zeus took over the earlier roles, and, in the form of a bull that came forth from the sea, abducted the high-born Phoenician Europa and brought her, significantly, to Crete.

Dionysus was another god of resurrection who was strongly linked to the bull. In a worship hymn from Olympia, at a festival for Hera, Dionysus is also invited to come as a bull, "with bull-foot raging." "Quite frequently he is portrayed with bull horns, and in Kyzikos he has a tauromorphic image," Walter Burkert relates, and refers also to an archaic myth in which Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and impiously eaten by the Titans.[24]

For the Greeks, the bull was strongly linked to the Cretan Bull: Theseus of Athens had to capture the ancient sacred bull of Marathon (the "Marathonian bull") before he faced the Minotaur (Greek for "Bull of Minos"), who the Greeks imagined as a man with the head of a bull at the center of the labyrinth. Minotaur was fabled to be born of the Queen and a bull, bringing the king to build the labyrinth to hide his family's shame. Living in solitude made the boy wild and ferocious, unable to be tamed or beaten. Yet Walter Burkert's constant warning is, "It is hazardous to project Greek tradition directly into the Bronze Age."[25] Only one Minoan image of a bull-headed man has been found, a tiny Minoan sealstone currently held in the Archaeological Museum of Chania.

In the Classical period of Greece, the bull and other animals identified with deities were separated as their agalma, a kind of heraldic show-piece that concretely signified their numinous presence.

Roman Empire

[edit]

The religious practices of the Roman Empire of the 2nd to 4th centuries included the taurobolium, in which a bull was sacrificed for the well-being of the people and the state. Around the mid-2nd century, the practice became identified with the worship of Magna Mater, but was not previously associated only with that cult (cultus). Public taurobolia, enlisting the benevolence of Magna Mater on behalf of the emperor, became common in Italy and Gaul, Hispania and Africa. The last public taurobolium for which there is an inscription was carried out at Mactar in Numidia at the close of the 3rd century. It was performed in honor of the emperors Diocletian and Maximian.

Another Roman mystery cult in which a sacrificial bull played a role was that of the 1st–4th century Mithraic Mysteries. In the so-called "tauroctony" artwork of that cult (cultus), and which appears in all its temples, the god Mithras is seen to slay a sacrificial bull. Although there has been a great deal of speculation on the subject, the myth (i.e. the "mystery", the understanding of which was the basis of the cult) that the scene was intended to represent remains unknown. Because the scene is accompanied by a great number of astrological allusions, the bull is generally assumed to represent the constellation of Taurus. The basic elements of the tauroctony scene were originally associated with Nike, the Greek goddess of victory.

Macrobius lists the bull as an animal sacred to the god Neto/Neito, possibly being sacrifices to the deity.[26]

Celts

[edit]Tarvos Trigaranus (the "bull with three cranes") is pictured on ancient Gaulish reliefs alongside images of gods, such as in the cathedrals at Trier and at Notre Dame de Paris. In Irish mythology, the Donn Cuailnge and the Finnbhennach are prized bulls that play a central role in the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge ("The Cattle Raid of Cooley"). Early medieval Irish texts also mention the tarbfeis (bull feast), a shamanistic ritual in which a bull would be sacrificed and a seer would sleep in the bull's hide to have a vision of the future king.[27]

Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century AD, describes a religious ceremony in Gaul in which white-clad druids climbed a sacred oak, cut down the mistletoe growing on it, sacrificed two white bulls and used the mistletoe to cure infertility:[28]

The druids—that is what they call their magicians—hold nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and a tree on which it is growing, provided it is Valonia oak. … Mistletoe is rare and when found it is gathered with great ceremony, and particularly on the sixth day of the moon….Hailing the moon in a native word that means 'healing all things,' they prepare a ritual sacrifice and banquet beneath a tree and bring up two white bulls, whose horns are bound for the first time on this occasion. A priest arrayed in white vestments climbs the tree and, with a golden sickle, cuts down the mistletoe, which is caught in a white cloak. Then finally they kill the victims, praying to a god to render his gift propitious to those on whom he has bestowed it. They believe that mistletoe given in drink will impart fertility to any animal that is barren and that it is an antidote to all poisons.[29]

Bull sacrifices at the time of the Lughnasa festival were recorded as late as the 18th century at Cois Fharraige in Ireland (where they were offered to Crom Dubh) and at Loch Maree in Scotland (where they were offered to Saint Máel Ruba).[30]

Medieval and modern and other uses

[edit]The practice of bullfighting in the Iberian Peninsula and southern France are connected with the legends of Saturnin of Toulouse and his protégé in Pamplona, Fermin. These are inseparably linked to bull-sacrifices by the vivid manner of their martyrdoms set by Christian hagiography in the third century.

In some Christian traditions, Nativity scenes are carved or assembled at Christmas time. Many show a bull or an ox near the baby Jesus, lying in a manger. Traditional songs of Christmas often tell of the bull and the donkey warming the infant with their breath. This refers (or, at least, is referred) to the beginning of the book of the prophet Isaiah, where he says: "The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master's crib." (Isaiah 1:3)

Oxen are some of the animals sacrificed by Greek Orthodox believers in some villages of Greece. It is specially associated to the feast of Saint Charalambos. This practice of kourbania has been repeatedly criticized by church authorities.

The ox is the symbol of Luke the Evangelist.[citation needed]

Among the Visigoths, the oxen pulling the wagon with the corpse of Saint Emilian lead to the correct burial site (San Millán de la Cogolla, La Rioja).

Taurus (Latin for "the Bull") is one of the constellations of the zodiac, which means it is crossed by the plane of the ecliptic. Taurus is a large and prominent constellation in the northern hemisphere's winter sky. It is one of the oldest constellations, dating back to at least the Early Bronze Age when it marked the location of the Sun during the spring equinox. Its importance to the agricultural calendar influenced various bull figures in the mythologies of Ancient Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

In his book 'Robin Hood: Green Lord of the Wildwood' (2016),John Matthews interprets the scene from the ballad in which Sir Richard-at-Lee awards, for the love of Robin Hood, a prize of a white bull to the winner of a wrestling match as seeming 'to hark back to an ancient time when the presentation of such a valuable, and probably sacred beast, would have represented an offering to the gods'. For Matthews, the Bull-running at Tutbury, mentioned in another Robin Hood ballad, may have had similar significance.[31]

See also

[edit]- Bucranium

- Bugonia

- Camahueto

- Cattle in religion

- Deer in mythology

- Golden calf

- Horned deity

- Mithraism

- Red heifer

- Taurobolium

References

[edit]- ^ Castor Marie-José, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia, Musée du Louvre

- ^ Sanders, N.K., trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh 1972. Penguin Classics. pp. 87-88

- ^ a b c d Dodson, Aidan (2005). "Bull Cults". Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. pp. 72–102. doi:10.5743/cairo/9789774248580.003.0004. ISBN 9789774248580.

- ^ Gordon & Schwabe (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Brill / Styx. pp. 104, 127–129. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5.

- ^ Gordon, Andrew H.; Schwabe, Calvin (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Brill / Styx. pp. 104, 127–129. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5.

- ^ Hawkes and Woolley, 1963; Vieyra, 1955

- ^ Pronk, Tijmen (January 1, 2009). "Sanskrit (v)rsabhá-, Greek αρσην, ερσην: the spraying bull of Indo-European?". Historische Sprachforschung – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ The Rig Veda. Wendy Doniger, trans. Penguin Classics. 1981.

- ^ Gupta, P.I. & T.R Hardaker. 2014. Punchmarked coins of the Indian subcontinent: Magadha-Mauryan series. Indian Numistamatic, Historical and Cultural Research Foundation. Mumbai.

- ^ Taasob, R. 2020. Representation of Wēś in early Kushan coinage: Royal or local cult? Afghanistan, 3(1): pp. 83-106.

- ^ Coins of India Through the Ages. Government Museum. Madras. 1953.

- ^ Indian Antiquary. Popular Prakashan. 1877. p. 222.

- ^ ""Kao – the sacred bull" by Laihui". e-pao.net.

- ^ "KAO – A Glimpse of Manipuri Opera". e-pao.net.

- ^ Burkert 1985

- ^ "A Calf and Its Shrine". Ashkelon: A Retrospecitve – 30 Years of the Leon Levy Expedition (Rockefeller Archaeological Museum). The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Mazar, Amihai (1999). "The 'Bull Site' and the 'Einun Pottery' Reconsidered". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 131 (2): 1944-148. doi:10.1179/peq.1999.131.2.144.

- ^ Miller, Patrick (2000), Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays, Continuum Int'l Publishing Group, p. 32, ISBN 1-84127-142-X.

- ^ biblelexicon.org, Exodus 32:4

- ^ biblelexicon.org, Nehemiah 9:18

- ^ "Hosea 10:5 The people who live in Samaria fear for the calf-idol of Beth Aven. Its people will mourn over it, and so will its idolatrous priests, those who had rejoiced over its splendor, because it is taken from them into exile". Bible.cc. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- ^ "1 Kings 7:25 The Sea stood on twelve bulls, three facing north, three facing west, three facing south and three facing east. The Sea rested on top of them, and their hindquarters were toward the center". Bible.cc. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- ^ "Jeremiah 52:20 The bronze from the two pillars, the Sea and the twelve bronze bulls under it, and the movable stands, which King Solomon had made for the temple of the LORD, was more than could be weighed". Bible.cc. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- ^ Burkert 1985 pp. 64, 132

- ^ Burkert 1985 p. 24

- ^ Macrobius, Saturnalia, Book I, XIX

- ^ Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1988). Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Syracuse University Press. p. 51.

- ^ Miranda J. Green. (2005) Exploring the World of the Druids. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28571-3. Page 18–19

- ^ Natural History, XVI, 95

- ^ MacNeill, Máire. The Festival of Lughnasa: A Study of the Survival of the Celtic Festival of the Beginning of Harvest. Oxford University Press, 1962. pp.407, 410

- ^ Matthews, John (2019). Robin Hood: Green Lord of the Wild Wood. Stroud: Amberly Publishing. pp. 23, 45. ISBN 978-1-4456-9077-3.

Sources

[edit]- Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion, 1985

- Campbell, Joseph Occidental Mythology "2.The Consort of the Bull", 1964.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta; Woolley, Leonard: Prehistory and the Beginnings of Civilization, v. 1 (NY, Harper & Row, 1963)

- Vieyra, Maurice: Hittite Art, 2300-750 B.C. (London, A. Tiranti, 1955)

- Jeremy B. Rutter, The Three Phases of the Taurobolium, Phoenix (1968).

- Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and its Remains (NY, Arno Press, 1976) pp. 113–114.

External links

[edit]- An exhibit on the tombs of Alaca Höyük at the Metropolitan Museum of Art includes one example of the bull standards.

- Bull Tattoo Art The image of the bull in tattoo art.