Battle of Drepana

| Battle of Drepana | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Punic War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Carthage | Roman Republic | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Adherbal | Publius Claudius Pulcher | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 100–130 ships | At least 123 ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None recorded |

| ||||||

Location of the battle, off the west coast of Sicily | |||||||

The naval Battle of Drepana (or Drepanum) took place in 249 BC during the First Punic War near Drepana (modern Trapani) in western Sicily, between a Carthaginian fleet under Adherbal and a Roman fleet commanded by Publius Claudius Pulcher.

Pulcher was blockading the Carthaginian stronghold of Lilybaeum (modern Marsala) when he decided to attack their fleet, which was in the harbour of the nearby city of Drepana. The Roman fleet sailed by night to carry out a surprise attack but became scattered in the dark. Adherbal was able to lead his fleet out to sea before it was trapped in harbour; having gained sea room in which to manoeuvre he then counter-attacked. The Romans were pinned against the shore, and after a day of fighting were heavily defeated by the more manoeuvrable Carthaginian ships with their better-trained crews. It was Carthage's greatest naval victory of the war; they turned to the maritime offensive after Drepana and all but swept the Romans from the sea. It was seven years before Rome again attempted to field a substantial fleet, while Carthage put most of its ships into reserve to save money and free up manpower.

Historical sources

[edit]The main source for almost every aspect of the First Punic War[note 1] is the historian Polybius (c. 200 – c.118 BC), a Greek sent to Rome in 167 BC as a hostage.[2][3] His works include a now-lost manual on military tactics,[4] but he is known today for The Histories, written sometime after 146 BC, or about a century after the Battle of Drepana.[2][5] Polybius's work is considered broadly objective and largely neutral as between Carthaginian and Roman points of view.[6][7]

Carthaginian written records were destroyed along with their capital, Carthage, in 146 BC and so Polybius's account of the First Punic War is based on several, now-lost, Greek and Latin sources.[8] Polybius was an analytical historian and wherever possible personally interviewed participants in the events he wrote about.[9][10] Only the first book of the 40 comprising The Histories deals with the First Punic War.[11] The accuracy of Polybius's account has been much debated over the past 150 years, but the modern consensus is to accept it largely at face value, and the details of the battle in modern sources are almost entirely based on interpretations of Polybius's account.[11][12][13] The modern historian Andrew Curry considers that "Polybius turns out to [be] fairly reliable";[14] while Dexter Hoyos describes him as "a remarkably well-informed, industrious, and insightful historian".[15] Other, later, histories of the war exist, but in fragmentary or summary form,[3][16] and they usually cover military operations on land in more detail than those at sea.[17] Modern historians usually also take into account the later histories of Diodorus Siculus and Dio Cassius, although the classicist Adrian Goldsworthy states that "Polybius' account is usually to be preferred when it differs with any of our other accounts".[10][note 2]

Other sources include inscriptions, archaeological evidence, and empirical evidence from reconstructions such as the trireme Olympias.[19] Since 2010 a number of artefacts have been recovered from the nearby site of the Battle of the Aegates, the final battle of the war, fought eight years later. Their analysis and the recovery of further items are ongoing.[20]

Background

[edit]Operations in Sicily

[edit]

In 264 BC the states of Carthage and Rome went to war, starting the First Punic War.[21] Carthage was a well-established maritime power in the western Mediterranean; Rome had recently unified mainland Italy south of the River Arno under its control. Rome's expansion into southern Italy probably made it inevitable that it would eventually clash with Carthage over Sicily on some pretext.[22] The immediate cause of the war was the issue of control of the Sicilian town of Messana (modern Messina).[23]

By 249 BC the war had lasted 15 years, with many changes of fortune. It had developed into a struggle in which the Romans were attempting to defeat the Carthaginians decisively and, at a minimum, control the whole of Sicily.[24] The Carthaginians were engaging in their traditional policy of waiting for their opponents to wear themselves out, in the expectation of then regaining some or all of their possessions and negotiating a mutually satisfactory peace treaty.[25] In 260 BC the Romans built a large fleet and over the following ten years defeated the Carthaginians in a succession of naval battles.[26] The Romans also slowly gained control of most of Sicily, including the major cities of Akragas (modern Agrigento; Agrigentum in Latin; captured in 262 BC) and Panormus (modern Palermo; captured in 254 BC).[27]

Ships

[edit]

During this war the standard warship was the quinquereme, meaning "five-oared".[17] The quinquereme was a galley, c. 45 metres (150 ft) long, c. 5 metres (16 ft) wide at water level, with its deck standing c. 3 metres (10 ft) above the sea, and displacing around 100 long tons (110 short tons; 100 tonnes). The galley expert John Coates suggests they could maintain 7 knots (8.1 mph; 13 km/h) for extended periods.[28] The modern replica galley Olympias has achieved speeds of 8.5 knots (9.8 mph; 15.7 km/h) and cruised at 4 knots (4.6 mph; 7.4 km/h) for hours on end.[17]

Vessels were built as cataphract, or "protected", ships – that is, fully decked over – so as to be better able to carry marines and catapults.[29][30] They had a separate "oar box" attached to the main hull which contained the rowers. These features allowed the hull to be strengthened, increased carrying capacity and improved conditions for the rowers.[31] The generally accepted theory regarding the arrangement of oarsmen in quinqueremes is that there would be sets – or files – of three oars, one above the other, with two oarsmen on each of the two uppermost oars and one on the lower, for a total of five oarsmen per file. This would be repeated down the side of a galley for a total of 28 files on each side; 168 oars in total.[32]

In 260 BC the Romans set out to construct a fleet and used a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme as a blueprint for their own.[33] As novice shipwrights, the Romans built copies that were heavier than the Carthaginian vessels, which made them slower and less manoeuvrable.[34] The quinquereme was the workhorse of the Roman and Carthaginian fleets throughout the Punic Wars, although hexaremes (six oarsmen per bank), quadriremes (four oarsmen per bank) and triremes (three oarsmen per bank) are also occasionally mentioned. So ubiquitous was the type that Polybius uses it as a shorthand for "warship" in general.[35] A quinquereme carried a crew of 300, of which 280 were oarsmen and 20 deck crew and officers;[36] it would normally also carry a complement of 40 marines,[37] and if battle was thought to be imminent, this would be increased to as many as 120.[38][39]

Getting the oarsmen to row as a unit, as well as execute more complex battle manoeuvres, required long and arduous training.[40] At least half of the oarsmen would need to have had some experience if the ship was to be handled effectively.[29] As a result, the Romans were initially at a disadvantage against the more experienced Carthaginians. To counter Carthaginian superiority, the Romans introduced the corvus, a bridge 1.2 metres (4 ft) wide and 11 metres (36 ft) long, with a heavy spike on the underside, which was designed to pierce and anchor into an enemy ship's deck.[38] This allowed Roman legionaries acting as marines to board enemy ships and capture them, rather than employing the previously traditional tactic of ramming. All warships were equipped with a ram, a triple set of 60-centimetre-wide (2 ft) bronze blades weighing up to 270 kilograms (600 lb) positioned at the waterline. They were made individually by the lost-wax method to fit immovably to a galley's prow and secured with bronze spikes.[41][42]

In the century prior to the Punic Wars, boarding had become increasingly common and ramming had declined, as the larger and heavier vessels adopted in this period lacked the speed and manoeuvrability necessary to ram, while their sturdier construction reduced the ram's effect even in the case of a successful attack. The Roman adaptation of the corvus was a continuation of this trend and compensated for their initial disadvantage in ship manoeuvring skills. The added weight in the prow compromised the ship's manoeuvrability, and in rough sea conditions the corvus became useless.[43][44][45] In 255 BC the Roman fleet was devastated by a storm while returning from Africa, with 384 ships sunk from a total of 464[note 3] and 100,000 men lost.[46][47] It is possible that the presence of the corvus made the Roman ships unusually unseaworthy and there is no record of them being used after this disaster.[48]

Prelude

[edit]Largely because of the Romans' use of the corvus, the Carthaginians were defeated in large naval battles at Mylae (260 BC), Sulci (257 BC), Ecnomus (256 BC) and Cape Hermaeum (255 BC).[49] During 252 and 251 BC the Roman army avoided battle, according to Polybius because they feared the war elephants which the Carthaginians had shipped to Sicily.[50][51] In 250 BC the Carthaginians attempted to recapture Panormus, but were defeated, losing most of their elephants.[52] Contemporary accounts do not report either side's other losses, and modern historians consider later claims of 20,000–30,000 Carthaginian casualties improbable.[53]

Encouraged by their victory at Panormus, the Romans moved against Lilybaeum – which was the main Carthaginian base on Sicily. A large army commanded by the year's consuls Publius Claudius Pulcher and Lucius Junius Pullus besieged the city. They had rebuilt their fleet, and 200 ships blockaded the harbour.[54] Early in the blockade, 50 Carthaginian quinqueremes gathered off the Aegates Islands, which lie 15–40 kilometres (9–25 mi) to the west of Sicily. Once there was a strong west wind, they sailed into Lilybaeum before the Romans could react. They unloaded reinforcements – either 10,000 or 4,000 according to different ancient sources[55] – and a large quantity of supplies. They evaded the Romans by leaving at night, evacuating the Carthaginian cavalry.[56]

The Romans sealed off the landward approach to Lilybaeum with earth and timber camps and walls. They made repeated attempts to block the harbour entrance with a heavy timber boom, but due to the prevailing sea conditions they were unsuccessful.[57] The Carthaginian garrison was kept supplied by blockade runners. These were light and manoeuvrable quinqueremes with highly trained crews and pilots who knew the shoals and currents of the difficult waters. Chief among the blockade runners was a galley captained by Hannibal the Rhodian, who taunted the Romans with the superiority of his vessel and crew. Eventually, the Romans captured Hannibal and his well-constructed galley.[58]

In 250 BC an additional 10,000 oarsmen were allocated to the Roman fleet. Pulcher, the senior consul, supported by a council of war, believed these gave him sufficient advantage to risk an attack on the Carthaginian fleet at Drepana, 25 kilometres (16 mi) north of Lilybaeum along the west coast of Sicily. The Roman fleet sailed on a moonless night to avoid detection and ensure surprise.[59][60] The Romans had a tradition of divining the likely fortune of a military endeavour by observing the actions of the sacred chickens. In the early morning they would be offered food: if they ate eagerly, the omens were good; if they refused it, the action was ill-fated.[61][62] When the solemn ceremony was performed on the way to Drepana, the chickens declined to eat. Infuriated, Pulcher pitched them overboard, exclaiming that if they were not hungry, then perhaps they were thirsty.[63] Polybius does not mention this, which has caused some modern historians to doubt its veracity.[64][65] T. P. Wiseman even thought that the whole episode was an invention from a hostile annalist to harm the reputation of the Claudii.[66]

Battle

[edit]

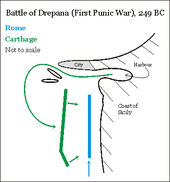

By dawn the Romans were close to Drepana but were experiencing problems. In the dark it had proved difficult to keep station. This was exacerbated by the recent incorporation of the 10,000 new oarsmen, who were not trained nor experienced at working with the existing crews. As a result, morning found the Roman ships spread out in a long, disorganised line. Pulcher's ship was towards the rear, possibly so he could discourage straggling.[59][60] The Carthaginian commander, Adherbal, was taken completely by surprise when his lookouts reported the approach of the Romans. However, his ships were ready for sea, and he immediately ordered them to take on board the garrison as marines, and to follow him out to sea.[65] The Roman fleet consisted of more than 120 ships; some sources give as many as 200. The Carthaginians had between 100 and 130 vessels. All of the warships, on both sides, were carrying full complements of marines.[67][68]

The more advanced of the Roman ships had reached the mouth of the harbour and were in a position to attempt to block it. However, Pulcher, seeing that surprise was lost, ordered them to fall back and concentrate in battle formation. This order took some time to transmit and resulted in some ships responding to it and turning into the paths of others still pressing forward and fouling them. So poor was the Roman seamanship that several ships collided, or sheared the oars off friendly vessels.[65] Meanwhile, Adherbal led his fleet past the confused Roman vanguard and continued west, passing between the city and two small islands to reach the open sea. Here they had room to manoeuvre and headed south, forming a line of battle that was parallel to the Romans. The Carthaginians managed to get five ships south of Pulcher's flagship, echeloned towards the shore, and so cut off the entire Roman fleet from its line of retreat to Lilybaeum.[65]

The Romans, meanwhile, had formed up in a line facing west, with the shore behind them, which prevented them from being outflanked. The Carthaginians attacked, and the weakness of Pulcher's dispositions became apparent. The Carthaginian ships were lighter built and more manoeuvrable, and their crews were more experienced and accustomed to working together. The Romans lacked the corvus to even the fight. On the other hand, the Carthaginians were probably outnumbered. The Carthaginians had the additional advantage that if an individual ship was getting the worse of a melee, it could reverse oars and withdraw; if the Roman vessel followed up, it left both of its flanks vulnerable. The Romans, with the shore close behind them, had no such advantage, and they attempted to stay in a tight formation for mutual protection. The battle was hard-fought and ground on through the day. The quality of the legionaries serving as the Roman marines, and their tight formation, made boarding difficult. But the Carthaginians handily outmanoeuvred the Romans, picking off exposed ships to ram, and steadily gaining more and more of an advantage. Eventually Roman discipline cracked; several ships were intentionally run aground so their crews could flee, and Pulcher led a successful breakout by 30 Roman ships, the only ones to survive the battle.[69][70][71]

The result was an utter Roman defeat, with 93 of their ships captured, an unknown number sunk,[72] and 20,000 men killed or captured.[73] It was Carthage's greatest naval victory of the war.[74]

Aftermath

[edit]

Shortly after the battle, Adherbal was reinforced by Carthalo with 70 ships.[note 4] Adherbal brought Carthalo's command up to 100 and sent him to raid Lilybaeum, where he burnt several Roman ships. A little later, he harried a Roman supply convoy of 800 transports, escorted by 120 warships, to such good effect that it was caught by a storm which sank all the vessels except for two.[77] The Carthaginians further exploited their victory by raiding, ineffectively, the coasts of Roman Italy in 248 BC.[78] The absence of Roman fleets then led Carthage to gradually decommission its navy, reducing the financial strain of building, maintaining and repairing ships, and providing and provisioning their crews.[79] They withdrew most of their warships from Sicily, and the war there entered a period of stalemate.[80] It was seven years after Drepana before Rome attempted to build another substantial fleet.[81][82]

Pulcher was recalled and charged with treason. He was convicted of a lesser charge – sacrilege over the chicken incident – narrowly escaped a death sentence and was exiled.[83] Pulcher's sister, Claudia, became infamous when, obstructed in a street blocked by poorer citizens, she wished aloud that her brother would lose another battle so as to thin the crowd.[78]

The war eventually ended in 241 BC after the Battle of the Aegates, with a Roman victory and an agreed peace. Henceforth Rome was the leading military power in the western Mediterranean and increasingly the Mediterranean region as a whole. The Romans had built over 1,000 galleys during the war; and this experience of building, manning, training, supplying and maintaining such numbers of ships laid the foundation for Rome's maritime dominance for 600 years.[84]

See also

[edit]Notes, citations and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The term Punic comes from the Latin word Punicus (or Poenicus), meaning "Carthaginian", and is a reference to the Carthaginians' Phoenician ancestry.[1]

- ^ Sources other than Polybius are discussed by Bernard Mineo in "Principal Literary Sources for the Punic Wars (apart from Polybius)".[18]

- ^ This assumes, per G. K. Tipps, that all 114 captured Carthaginian vessels were sailing with the Romans.[46]

- ^ Two modern historians have speculated that Pulcher may have been aware of this impending reinforcement and that, if so, it was a decisive factor in his decision to attack while his opponent was weaker.[75][76]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Sidwell & Jones 1998, p. 16.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 20.

- ^ a b Tipps 1985, p. 432.

- ^ Shutt 1938, p. 53.

- ^ Walbank 1990, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. x–xi.

- ^ Hau 2016, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Shutt 1938, p. 55.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 21.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. x–xi, 82–84.

- ^ Tipps 1985, pp. 432–433.

- ^ Curry 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, p. 102.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Goldsworthy 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Mineo 2015, pp. 111–127.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 23, 98.

- ^ Royal & Tusa 2019, pp. 13–18.

- ^ Warmington 1993, p. 168.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 92, 96–97, 130.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 97, 99–100, 107–108, 110–115, 115–116.

- ^ Rankov 2011, p. 158.

- ^ Coates 2004, p. 138.

- ^ a b de Souza 2008, p. 358.

- ^ Meijer 1986, p. 120.

- ^ Coates 2004, pp. 129–130, 138–139.

- ^ Casson 1995, p. 101.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 97, 99–100.

- ^ Murray 2011, p. 69.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 104.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Tipps 1985, p. 435.

- ^ a b Casson 1995, p. 121.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Casson 1995, pp. 278–280.

- ^ Curry 2012, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Tusa & Royal 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Wallinga 1956, pp. 77–90.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 100–101, 103.

- ^ a b Tipps 1985, p. 438.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 189.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 112, 117.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 107–108, 110–115, 115–116.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 118.

- ^ Rankov 2011, p. 159.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 190.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 85.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Lazenby 1996, p. 132.

- ^ Nuttall 1840, pp. 439, 601.

- ^ Jaucourt 2007.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 191.

- ^ Walbank 1957, p. 113, 114.

- ^ a b c d Lazenby 1996, p. 134.

- ^ Wiseman 1979, p. 90–92, 110, 111, 131.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 133.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 121.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 134–136.

- ^ Tarn 1907, p. 54.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 133, 136.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 88.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 136.

- ^ Konrad 2015, p. 200 n.30.

- ^ Tarn 1907, pp. 48–60.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 88–91.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 192.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, pp. 92, 94.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 122.

- ^ Rankov 2011, p. 162.

- ^ Rankov 2011, p. 163.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 128–129, 357, 359–360.

Sources

[edit]- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Casson, Lionel (1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5130-8.

- Coates, John F. (2004). "The Naval Architecture and Oar Systems of Ancient Galleys". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Age of the Galley: Mediterranean Oared Vessels since Pre-Classical Times. London: Chrysalis. pp. 127–141. ISBN 978-0-85177-955-3.

- Curry, Anne (2012). "The Weapon That Changed History". Archaeology. 65 (1): 32–37. JSTOR 41780760.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix Books. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hau, Lisa Irene (2016). Moral History from Herodotus to Diodorus Siculus. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-1107-3.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015) [2011]. A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Jaucourt, Louis, chevalier de (2007). "Sacred Chickens". In Diderot, Denis; le Rond d'Alembert, Jean (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Goodman, Dena. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library. p. 203. hdl:2027/spo.did2222.0000.865.

Translation of "Poulets Sacrés," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 13. Paris, 1765.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Konrad, C. (2015). "After Drepana". The Classical Quarterly. 65 (1): 192–203. doi:10.1017/S0009838814000032. S2CID 231889835.

- Lazenby, John Francis (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2674-0. (registration required)

- Meijer, Fik (1986). A History of Seafaring in the Classical World. London; Sydney: Croom and Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-3565-0.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Mineo, Bernard (2015) [2011]. "Principal Literary Sources for the Punic Wars (apart from Polybius)". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Murray, William M. (2011). The Age of Titans: The Rise and Fall of the Great Hellenistic Navies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993240-5.

- Nuttall, P. Austin (1840). A Classical and Archaeological Dictionary of the Manners, Customs, Laws, Institutions, Arts, Etc. of the Celebrated Nations of Antiquity, and of the Middle Ages: To which is Prefixed A Synoptical and Chronological View of Ancient History. London: Whittaker. OCLC 778642211.

- Prag, Jonathan (2014). "Bronze rostra from the Egadi Islands off NW Sicily: the Latin inscriptions". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 27: 33–59. doi:10.1017/S1047759414001159. S2CID 162932300.

- Rankov, Boris (2011). "A War of Phases: Strategies and Stalemates". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 149–166. ISBN 978-1-4051-7600-2.

- Royal, Jeffrey G.; Tusa, Sebastiano, eds. (2019). The Site of the Battle of the Aegates Islands at the End of the First Punic War. Fieldwork, Analyses and Perspectives, 2005–2015. Bibliotheca Archaeologica. Vol. 60. Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider. ISBN 978-88-913-1835-0.

- Shutt, R.J.H. (1938). "Polybius: A Sketch". Greece & Rome. 8 (22): 50–57. doi:10.1017/S001738350000588X. JSTOR 642112. S2CID 162905667.

- Sidwell, Keith C.; Jones, Peter V. (1998). The World of Rome: an Introduction to Roman Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38600-5.

- de Souza, Philip (2008). "Naval Forces". In Sabin, Philip; van Wees, Hans & Whitby, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, Volume 1: Greece, the Hellenistic World and the Rise of Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 357–367. ISBN 978-0-521-85779-6.

- Tarn, W.W. (1907). "The Fleets of the First Punic War". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 27: 48–60. doi:10.2307/624404. JSTOR 624404. S2CID 163828693.

- Tipps, G.K. (1985). "The Battle of Ecnomus". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 34 (4): 432–465. JSTOR 4435938.

- Tusa, Sebastiano; Royal, Jeffrey (2012). "The Landscape of the Naval Battle at the Egadi Islands (241 B.C.)" (PDF). Journal of Roman Archaeology. 25: 7–48. doi:10.1017/S1047759400001124. S2CID 159518193. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-26. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- Walbank, F.W. (1957). A Historical Commentary on Polybius. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198141525.

- Walbank, F.W. (1990). Polybius. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06981-7.

- Wallinga, Herman Tammo (1956). The Boarding-Bridge of the Romans. Groningen; Djakarta: J.B. Wolters. OCLC 458845955.

- Warmington, Brian Herbert (1993) [1960]. Carthage. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-56619-210-1.

- Wiseman, Timothy Peter (1979). Clio's cosmetics: three studies in Greco-Roman literature. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0718511654.

Further reading

[edit]- Polybius. "chapters 49–52". The Histories I. Translation by William Roger Paton on Wikisource.