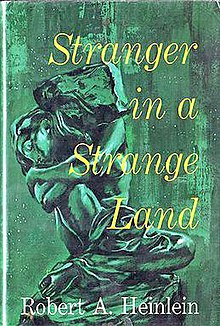

Stranger in a Strange Land

| |

| Author | Robert A. Heinlein |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | G. P. Putnam's Sons |

Publication date | June 1, 1961 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 408 (208,018 words) |

| ISBN | 978-0-441-79034-0 |

Stranger in a Strange Land is a 1961 science fiction novel by American author Robert A. Heinlein. It tells the story of Valentine Michael Smith, a human who comes to Earth in early adulthood after being born on the planet Mars and raised by Martians, and explores his interaction with and eventual transformation of Terran culture.

The title "Stranger in a Strange Land" is a direct quotation from the King James Bible (taken from Exodus 2:22).[1] The working title for the book was "A Martian Named Smith", which was also the name of the screenplay started by a character at the end of the novel.[2]

Heinlein's widow Virginia arranged to have the original unedited manuscript published in 1991, three years after Heinlein's death. Critics disagree about which version is superior.[3]

Stranger in a Strange Land won the 1962 Hugo Award for Best Novel and became the first science fiction novel to enter The New York Times Book Review's best-seller list. In 2012, the Library of Congress named it one of 88 "Books that Shaped America".[4]

Plot

[edit]Prior to World War III, the crewed spacecraft Envoy is launched toward Mars, but all contact is lost shortly before landing. Twenty-five years later, the spacecraft Champion makes contact with the inhabitants of Mars and finds a single survivor, Valentine Michael Smith. Born on the Envoy, he was raised entirely by the Martians. He is ordered by them to accompany the returning expedition.

Smith is confined at Bethesda Hospital, where, having never seen a human female, he is attended by male staff only. Seeing that restriction as a challenge, Nurse Gillian Boardman eludes the guards and goes in to see Smith. By sharing a glass of water with him, she inadvertently becomes his first "water brother", a profound relationship by Martian standards, as water on Mars is extremely scarce.

Gillian's lover, reporter Ben Caxton, discovers that Smith is extremely wealthy. Ben is seized by the government, and Gillian persuades Smith to leave the hospital with her. Gillian takes Smith to Jubal Harshaw, a famous author, physician and lawyer. Eventually, Harshaw arranges freedom for Smith and recognition that human law, which would have granted ownership of Mars to Smith, has no applicability to a planet that is already inhabited by intelligent life.

Smith becomes a celebrity and is feted by the Earth's elite. He investigates many religions, including the Fosterite Church of the New Revelation, a populist megachurch in which sexuality, gambling, alcohol consumption, and similar activities are allowed and even encouraged and considered "sinning" only when they are not under church auspices. Smith has a brief career as a magician in a carnival, in which he and Gillian befriend the show's tattooed lady.

Smith starts a Martian-influenced "Church of All Worlds", combining elements of the Fosterite cult with Western esotericism. The church is besieged by Fosterites for practicing "blasphemy", and the church building is destroyed, but unknown to the public, Smith's followers teleport to safety.

Smith is arrested by the police, but escapes and returns to his followers, later explaining to Jubal that his gigantic fortune has been bequeathed to the church. With that wealth and their new abilities, church members will be able to reorganize human societies and cultures.

Smith is killed by a mob raised against him by the Fosterites. Jubal and some of the church members return to Jubal's home to regroup and prepare to found new Church of All Worlds congregations. Smith reappears in the afterlife to replace the Fosterites' founder, amid hints that Smith was an incarnation of the Archangel Michael.

Characters

[edit]Heinlein named his main character "Smith" because of a speech he made at a science fiction convention regarding the unpronounceable names assigned to extraterrestrials. After describing the importance of establishing a dramatic difference between humans and aliens, Heinlein concluded, "Besides, whoever heard of a Martian named Smith?"[2] The title Stranger in a Strange Land is taken from the King James Version of Exodus 2:22, "And she bore him a son, and he called his name Gershom: for he said, I have been a stranger in a strange land".[1]

In the preface to the uncut, original version of the book reissued in 1991, Heinlein's widow, Virginia, wrote: "The given names of the chief characters have great importance to the plot. They were carefully selected: Jubal means 'the father of all,' Michael stands for 'Who is like God?'".

- Valentine Michael Smith

- Known as Michael Smith or "Mike", the "Man from Mars" is born on Mars in the interval between the landing of the Envoy and the arrival of the Champion. He is 20 years old when the Champion arrives and brings him to Earth.

- Gillian (Jill) Boardman

- A nurse at Bethesda Hospital who sneaks Mike out of government custody. She plays a key role in introducing him to human culture and becomes one of his closest confidantes and a central figure in the Church of All Worlds, which Mike develops.

- Ben Caxton

- An early love interest of Jill and an investigative journalist (Jill sees him as of the "lippmann", political, rather than the "winchell", or celebrity gossip inclination), who masterminds Mike's initial freedom from custody. He joins Mike's inner circle but remains somewhat skeptical at first of the social order that it develops.

- Jubal Harshaw

- A popular writer, lawyer, and doctor, now semi-retired to a house in the Pocono Mountains, an influential but reclusive public figure who provides pivotal support for Mike's independence and a safe haven for him. Elderly but in good health, he serves as a father figure for the inner circle while keeping a suspicious distance from it. The character's name was chosen by Heinlein to have unusual overtones, like Jonathan Hoag.[5] Mike enshrines him (much to Harshaw's initial chagrin) as the patron saint of the church he founds.

- Anne, Miriam, Dorcas

- Harshaw's three personal/professional secretaries, who live with him and take turns as his "front", responding to his instructions. Anne is certified as a Fair Witness, empowered to provide objective legal testimony about events that she witnesses. All three become early acolytes of Michael's church.

- Duke, Larry

- Handymen who work for Harshaw and live in his estate; they also become central members of the church.

- Dr. "Stinky" Mahmoud

- A semanticist, crew member of the Champion and the second human (after Mike) to gain a working knowledge of the Martian language but does not "grok" the language. He becomes a member of the church while retaining his Muslim faith.

- Patty Paiwonski

- A "tattooed lady" and snake handler at the circus Mike and Jill join for a time. She has ties to the Fosterite church, which she retains as a member of Mike's inner circle.

- Joseph Douglas

- Secretary-General of the Federation of Free States, which has evolved indirectly from the United Nations into a true world government.

- Alice Douglas

- Sometimes called "Agnes", Joe Douglas' wife. As the First Lady, she manipulates her husband, making major economic, political, and staffing decisions and frequently consults astrologer Becky Vesant for major decisions.

- Foster

- The founder of the Church of the New Revelation (Fosterite), who now exists as an archangel.

- Digby

- Foster's successor as head of the Fosterite Church; he becomes an archangel under Foster after Mike "discorporates" him.

Development

[edit]Originally titled The Heretic, the book was written in part as a deliberate attempt to challenge social norms. In the course of the story, Heinlein uses Smith's open-mindedness to re-evaluate such institutions as religion, money, monogamy, and the fear of death. Heinlein completed writing it ten years after he had plotted it out in detail. He later wrote, "I had been in no hurry to finish it, as that story could not be published commercially until the public mores changed. I could see them changing and it turned out that I had timed it right."[6]

Heinlein got the idea for the novel when he and his wife Virginia were brainstorming one evening in 1948. She suggested a new version of Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book (1894), but with a child raised by Martians instead of wolves. He decided to go further with the idea and worked on the story on and off for more than a decade,[7] believing that contemporary society was not yet ready for it.[8]

Heinlein was surprised that some readers thought the book described how he believed society should be organized, explaining: "I was not giving answers. I was trying to shake the reader loose from some preconceptions and induce him to think for himself, along new and fresh lines. In consequence, each reader gets something different out of that book because he himself supplies the answers ... It is an invitation to think – not to believe."

His editors at Putnam required him to cut its 220,000-word length down to 160,000 words before publication.[citation needed]

Heinlein himself remarked in a letter he wrote to Oberon Zell-Ravenheart in 1972 that he thought his shorter, edited version was better.[9] Heinlein also added some new material to the shorter version.

The book was dedicated in part to science fiction author Philip José Farmer, who had explored sexual themes in works such as The Lovers (1952). It was also influenced by the satiric fantasies of James Branch Cabell.

Reception

[edit]Heinlein's deliberately provocative book generated considerable controversy.[10] The free love and commune living aspects of the Church of All Worlds led to the book's exclusion from school reading lists. After it was rumored to be associated with Charles Manson, it was removed from school libraries, as well.[citation needed]

Writing in The New York Times, Orville Prescott received the novel caustically, describing it as a "disastrous mishmash of science fiction, laborious humor, dreary social satire, and cheap eroticism"; he characterized Stranger in a Strange Land as "puerile and ludicrous", saying "when a non-stop orgy is combined with a lot of preposterous chatter, it becomes unendurable, an affront to the patience and intelligence of readers".[11] Galaxy reviewer Floyd C. Gale rated the novel 3.5 stars out of five, saying "the book's shortcomings lie not so much in its emancipation as in the fact that Heinlein has bitten off too large a chewing portion".[12]

Despite such reviews, Stranger in a Strange Land won the 1962 Hugo Award for Best Novel[13] and became the first science fiction novel to enter The New York Times Book Review's best-seller list.[10] In 2012, it was included in a Library of Congress exhibition of "Books That Shaped America".[14]

Critics have also suggested that Jubal Harshaw is actually a stand-in for Robert Heinlein himself, based on similarities in career choice and general disposition,[15] though Harshaw is much older than Heinlein was at the time of writing. Literary critic Dan Schneider wrote that Harshaw's belief in his own free will, was one "which Mike, Jill, and the Fosterites misinterpret as a pandeistic urge, 'Thou art God!'"[16]

Influence

[edit]The book significantly influenced modern culture in a variety of ways.

Church of All Worlds

[edit]A central element of the second half of the novel is the religious movement founded by Smith, the "Church of All Worlds", an initiatory mystery religion blending elements of paganism and revivalism, with psychic training and instruction in the Martian language. In 1968, Oberon Zell-Ravenheart (then Tim Zell) founded the Church of All Worlds, a Neopagan religious organization modeled in many ways after the fictional organization in the novel.[17] The spiritual path included several ideas from the book, including polyamory, non-mainstream family structures, social libertarianism, water-sharing rituals, an acceptance of all religious paths by a single tradition, and the use of several terms such as "grok", "Thou art God", and "Never Thirst".

Heinlein objected to Zell's lumping him with other writers such as Ayn Rand and Robert Rimmer; Heinlein felt that those writers used their art for propaganda purposes, while he simply asked questions of the reader, expecting each reader to answer for him- or herself. He wrote to Zell in a letter: "... each reader gets something different out of the book because he himself supplies the answers. If I managed to shake him loose from some prejudice, preconception or unexamined assumption, that was all I intended to do."[18]

Though Heinlein was neither a member nor a promoter of the Church, it was formed including frequent correspondence between Zell and Heinlein, and Heinlein was a paid subscriber to the Church's magazine Green Egg.[citation needed] This Church still exists as a 501(c)(3) recognized religious organization incorporated in California, with membership worldwide, and it remains an active part of the neopagan community.[19]

Grok

[edit]The word "grok", coined in the novel, made its way into the English language. In Heinlein's invented Martian language, "grok" literally means "to drink" and figuratively means "to comprehend", "to love", and "to be one with". The word rapidly became common parlance among science fiction fans, hippies, and later computer programmers[20] and hackers,[21] and has since entered the Oxford English Dictionary.[22]

Fair Witness

[edit]The profession of Fair Witness, invented for the novel, has been cited in such varied contexts as environmentalism,[23] psychology,[24] technology,[25] digital signatures,[26] and science,[27] as well as in books on leadership[28] and Sufism.[29] A Fair Witness is an individual trained to observe events and report exactly what is seen and heard, making no extrapolations or assumptions. While wearing the Fair Witness uniform of a white robe, they are presumed to be observing and opining in their professional capacity.[30] Works that refer to the Fair Witness emphasize the profession's impartiality, integrity, objectivity, and reliability.[31][32]

An example from the book illustrates the role of Fair Witness when Anne is asked what color a house is. She answers, "It's white on this side." The character Jubal then explains, "You see? It doesn't occur to Anne to infer that the other side is white, too. All the King's horses couldn't force her to commit herself... unless she went there and looked – and even then she wouldn't assume that it stayed white after she left."[30]

Waterbed

[edit]Stranger in a Strange Land contains an early description of the waterbed, an invention that made its real-world debut in 1968. Charles Hall, who submitted a waterbed design to the United States patent office, was initially refused a patent on the grounds that Heinlein's descriptions in Stranger in a Strange Land and another novel, Double Star (1956), constituted prior art.[33]

In popular culture

[edit]- Heinlein's novella Lost Legacy (1941) lends its theme, and possibly some characters, to Stranger in a Strange Land. In a relevant part of the story, Joan Freeman is described as feeling like "a stranger in a strange land".[34]

- The Police released an Andy Summers–penned song titled "Friends", as the B-side to their hit "Don't Stand So Close to Me" (1980), that referenced the novel. Summers claimed that it "was about eating your friends, or 'grocking' them as [Stranger in a Strange Land] put it".[35]

- In November 2016, Syfy announced plans to develop a TV series based on the novel with Paramount Television and Universal Cable Productions co-producing the series.[36]

- Stranger in a Strange Land is included in Billy Joel's song "We Didn't Start the Fire", which is based on significant events of the mid- to late 20th century.

Publication history

[edit]Two major versions of this book exist:

- The 1961 version which, at the publisher's request, Heinlein cut by 25% in length. Approximately 60,000 words were removed from the original manuscript, including some sharp criticism of American attitudes toward sex and religion.[10] The book was marketed to a mainstream readership, and was the first science fiction novel to be listed on The New York Times Best Seller list for fiction. By 1997, over 100,000 copies of the hardback edition had been sold along with nearly five million copies of the paperback.[10] None of his later novels would match this level of success.[37]

- The 1991 version, retrieved from Heinlein's archives in the University of California, Santa Cruz, Special Collections Department by Heinlein's widow, Virginia, and published posthumously, which reproduces the original manuscript and restores all cuts. It came about because in 1989, Virginia renewed the copyright to Stranger and cancelled the existing publication contracts in accordance with the Copyright Act of 1976. Both Heinlein's agent and his publisher (which had new senior editors) agreed that the uncut version was better: readers are used to longer books, and what was seen as objectionable in 1961 was no longer so 30 years later.[38]

Heinlein himself remarked in a letter he wrote to Oberon Zell-Ravenheart in 1972 that he thought his shorter, edited version was better. He wrote, "SISL was never censored by anyone in any fashion. The first draft was nearly twice as long as the published version. I cut it myself to bring it down to a commercial length. But I did not leave out anything of any importance; I simply trimmed all possible excess verbiage. Perhaps you have noticed that it reads 'fast' despite its length; that is why. ... The original, longest version of SISL ... is really not worth your trouble, as it is the same story throughout – simply not as well told. With it is the brushpenned version which shows exactly what was cut out – nothing worth reading, that is. I learned to write for pulp magazines, in which one was paid by the yard rather than by the package; it was not until I started writing for the Saturday Evening Post that I learned the virtue of brevity."[9]

Additionally, since Heinlein added material while he was editing the manuscript for the commercial release, the 1991 publication of the original manuscript is missing some material that was in the novel when it was first published.[39]

Editions

[edit]Many editions exist:[40]

- June 1, 1961, Putnam Publishing Group, hardcover, ISBN 0-399-10772-X[41]

- Avon, NY, first paperback edition, 1962.

- 1965, New English Library Ltd, (London).

- March 1968, Berkley Medallion, paperback, ISBN 0-425-04688-5

- July 1970, New English Library Ltd, (London). 400 pages, paperback. (third 'new edition', August 1971 reprint, NEL 2844.)

- 1972, Capricorn Books, 408 pages, ISBN 0-399-50268-8

- October 1975, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-03067-9

- November 1977, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-03782-7

- July 1979, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-04377-0

- September 1980, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-04688-5

- July 1982, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-05833-6

- July 1983, Penguin Putnam, paperback, ISBN 0-425-06490-5

- January 1984, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-07142-1

- May 1, 1984, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-05216-8

- December 1984, Berkley Publishing Group, ISBN 0-425-08094-3

- November 1986, Berkley Publishing Group, paperback, ISBN 0-425-10147-9

- 1989, Easton Press, leather bound hardcover, 414 pages

- January 1991, original uncut edition, Ace/Putnam, hardcover, ISBN 0-399-13586-3

- May 3, 1992, original uncut edition, Hodder and Stoughton, mass market paperback, 655 pages, ISBN 0-450-54742-6

- 1995, Easton Press (MBI, Inc.), original uncut edition, leather bound hardcover, 525 pages

- August 1, 1995, ACE Charter, paperback, 438 pages, ISBN 0-441-79034-8

- April 1, 1996, Blackstone Audio, cassette audiobook, ISBN 0-7861-0952-1

- October 1, 1999, Sagebrush, library binding, ISBN 0-8085-2087-3

- June 1, 2002, Blackstone Audio, cassette audiobook, ISBN 0-7861-2229-3

- January 2003, Turtleback Books distributed by Demco Media, hardcover, ISBN 0-606-25126-X

- November 1, 2003, Blackstone Audio, CD audiobook, ISBN 0-7861-8848-0

- March 14, 2005, Hodder and Stoughton, paperback, 655 pages, ISBN 0-340-83795-0

- October 25, 2016, Penguin Books, hardcover, 498 pages, ISBN 978-0143111627

- 2020, Folio Society, original uncut edition, slipcased hardcover, 616 pages

- 2021, Suntup Press, original uncut edition, slipcased hardcover, 636 pages, ISBN 1-951-15169-0

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b Gale, Cengage Learning (13 March 2015). A Study Guide for Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land. Gale, Cengage Learning. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-1-4103-2078-0. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ a b Patterson, William; Thornton, Andrew (2001). The Martian Named Smith: Critical Perspectives On Robert A. Heinlein's 'Stranger In A Strange Land'. Nytrosyncretic Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-9679874-2-2. Archived from the original on 2010-08-20.

- ^ Woo, Elaine (26 January 2003). "Virginia Heinlein, 86; Wife, Muse and Literary Guardian of Celebrated Science Fiction Writer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Books that Shaped America". Library of Congress. 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ J. Neil Schulman (1999-01-31). The Robert Heinlein Interview and Other Heinleiniana. Pulpless.Com. p. 170. ISBN 1-58445-015-0.

- ^ Expanded Universe, p. 403.

- ^ H. Patterson, Jr, William. "Biography: Robert A. Heinlein". Heinlein Society. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Suplee, Curt (1984-09-05). "In the Strange Land Of Robert Heinlein". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2021-07-29. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ a b Letter from Robert A. Heinlein to Oberon Zell, Green Egg magazine, Vol. XXII. No. 85 (Beltane, 1989).

- ^ a b c d Vonnegut, Kurt (9 December 1990). "Heinlein Gets the Last Word". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Prescott, Orville (August 4, 1961). "Books of The Times" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 19. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Gale, Floyd C. (June 1962). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 191–194.

- ^ Scott MacFarlane (12 February 2007). The Hippie Narrative: A Literary Perspective on the Counterculture. McFarland. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-0-7864-8119-4. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Library of Congress issues list of "Books That Shaped America"". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Marshall B. Tymn (1981). Masterplots II.: American fiction series, Volume 4. Salem Press. ISBN 978-0-89356-460-5. Archived from the original on 2022-08-23. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Dan Schneider, Review of Stranger In A Strange Land (The Uncut Version), by Robert A. Heinlein Archived 2013-08-04 at the Wayback Machine (29 July 2005).

- ^ Cusack, Carole M. (2009). "Science Fiction as Scripture: Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land and the Church of All Worlds". Literature & Aesthetics. 19 (2). ISSN 2200-0437.

- ^ William H. Patterson Jr., 2014, Robert A. Heinlein In Dialogue with His Century, Vol. 2, pg. 597

- ^ Iacchus, (CAW Priest). "What is the Church of All Worlds?". Church of All Worlds. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ "grok | Logstash Reference [5.4] | Elastic". www.elastic.co. Archived from the original on 2017-05-01. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ^ Raymond, Eric S., ed. (December 29, 2003). "grok". The Jargon File. 4.4.7. Archived from the original on December 20, 2017.

- ^ "Grok". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-11-16.

- ^ Willard, Daniel E. (1980). "Ecologists, Environmental Litigation, and Forensic Ecology". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 61 (1): 14–18. doi:10.2307/20166224. JSTOR 20166224. S2CID 128702372.

- ^ Erard, Robert E. (September 2016). "If It Walks Like a Duck: a Case of Confirmatory Bias". Psychological Injury and Law. 9 (3): 275–277. doi:10.1007/s12207-016-9262-6. S2CID 148049120.

- ^ Martellaro, John. "Google Glass, SciFi, Robert Heinlein & the Fair Witness Effect". The Mac Observer. Retrieved 2 May 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gripman, David L. (Spring 1999). "Electronic Document Certification: A Primer on the Technology Behind Digital Signatures". The John Marshall Journal of Information Technology & Privacy Law. 17 (3). Archived from the original on 2020-05-01. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

- ^ Stoskopf, M. K. (2005). "Observation and Cogitation: How Serendipity Provides the Building Blocks of Scientific Discovery". ILAR Journal. 46 (4): 332–337. doi:10.1093/ilar.46.4.332. PMID 16179740.

- ^ Andersen, Erika (2012). Leading So People Will Follow. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-1118379875. Archived from the original on 2022-08-23. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Bayman, Henry (2001). The Station of No Station: Open Secrets of the Sufis. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1556432408. Archived from the original on 2022-08-23. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ a b Still, Julie M. (March 2011). "Librarian as Fair Witness: A Comparison of Heinlein's Futuristic Occupation and Today's Evolving Information Professional" (PDF). LIBRES Library and Information Science Research Electronic Journal. 21 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

- ^ Atkinson, Ross (April 2005). "Transversality and the Role of the Library as Fair Witness". The Library Quarterly. 75 (2): 169–189. doi:10.1086/431332. S2CID 143659992.

- ^ Andersen, Erika (2016). Be Bad First: Get Good at Things Fast to Stay Ready for the Future. Routledge. ISBN 978-1629561080.

- ^ Garmon, Jay (2005-02-01). "Geek Trivia: Comic relief". Tech Republic. TechRepublic. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A. (November 1941). "Lost Legacy". Super Science Stories. Chapter 10

- ^ "'Don't Stand So Close to Me'/'Friends'". sting.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Keene, Allison (15 November 2016). "'Stranger in a Strange Land' TV Series Heads to Syfy". Collider.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ BookCaps; BookCaps Study Guides Staff (2011). Stranger in a Strange Land: BookCaps Study Guide. BookCaps Study Guides. ISBN 978-1-61042-937-5. Archived from the original on 2019-09-20. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- ^ Jones, David (16 December 1990). "Heinlein's Original 'Stranger' Restored". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Oberon Zell. "Comment dated 22 Aug 2010 in Polyandry in the News!". Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Title: Stranger in a Strange Land". isfdb.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 2013-06-10. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ "Stranger in a Strange Land - Robert A. Heinlein". ISBNdb entry. Putnam Adult. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

Bibliography

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1995). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 1386. ISBN 978-0-312-13486-0.

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1995). The Multimedia Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (CD-ROM ed.). Danbury, CT: Grolier. ISBN 978-0-7172-3999-3.

- Nicholls, Peter (1979). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts, UK: Granada Publishing. p. 672. ISBN 978-0-586-05380-5.

- Jakubowski, Maxim; Edwards, Malcolm (1983). The Complete Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy Lists. St Albans, Herts, UK: Granada Publishing. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-586-05678-3.

- Panshin, Alexei (1968). Heinlein in Dimension: A Critical Analysis. Chicago: Advent Publishers. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-911682-12-0.

- Patterson, William H. Jr.; Thornton, Andrew (2001). The Martian Named Smith: Critical Perspectives on Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land. Sacramento: Nitrosyncretic Press. ISBN 978-0-9679874-2-2.

- Pringle, David (1990). The Ultimate Guide to Science Fiction. London: Grafton Books. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-246-13635-0.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent Publishers. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-911682-20-5.

External links

[edit]- Stranger in a Strange Land title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Stranger in a Strange Land at Open Library