Babes in Toyland (1961 film)

| Babes in Toyland | |

|---|---|

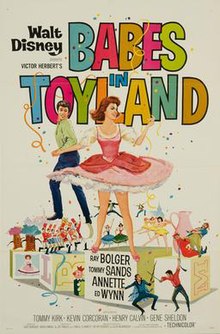

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Donohue |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Babes in Toyland by Victor Herbert and Glen MacDonough |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Edward Colman |

| Edited by | Robert Stafford |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million[2] |

| Box office | $4.6 million (U.S./Canada rentals)[3] |

Babes in Toyland is a 1961 American Christmas musical film directed by Jack Donohue and produced by Walt Disney Productions. It stars Ray Bolger as Barnaby, Tommy Sands as Tom Piper, Annette Funicello as Mary Contrary, and Ed Wynn as the Toymaker.[4]

The film is based upon Victor Herbert's popular 1903 operetta Babes in Toyland. There had been a 1934 film also titled Babes in Toyland starring Laurel and Hardy, and three television adaptations prior to the Disney film, but Disney's was only the second film version of the operetta released to movie theatres and the first in Technicolor. The plot, and in some cases the music, bear little resemblance to the original, as Disney had most of the lyrics rewritten and some of the song tempos drastically changed, including the memorable song "Toyland", a slow ballad, which was sped up with only the chorus sung in a march-like rhythm.[2]

The toy soldiers later appeared in Christmas parades at the Disney theme parks around the world.

Funicello said it was her favorite filmmaking experience.[5]

Plot

[edit]A stage play begins, presented by Mother Goose and her talking goose, Sylvester, about Mary Contrary and Tom Piper, who are about to be married. The miserly and villainous Barnaby hires two crooks, dimwitted Gonzorgo and silent Roderigo. They are to throw Tom into the sea and steal Mary's sheep, depriving her of her means of support, to force her to marry Barnaby. Mary is unaware that she is the heiress to a fortune, but Barnaby is aware and wants it all for himself. Gonzorgo and Roderigo decide to sell Tom to the Gypsies instead of drowning him, in order to collect a double payment.

Gonzorgo and Roderigo return and tell Mary, Barnaby, and the citizens of Mother Goose Land that Tom has accidentally drowned. They show Mary a forged letter in which Tom tells Mary he is abandoning her, and she would be better off marrying Barnaby. Mary, believing she is destitute, reluctantly accepts the proposal from Barnaby. Barnaby unknowingly arranges for the same Gypsies who have Tom to provide entertainment for the wedding. Tom, disguised as the Gypsy Floretta, reveals himself, and Barnaby pursues the frightened Gonzorgo and Roderigo, furious at their deception.

One of the children who lives with Mary informs her of some sheep tracks leading into the Forest of No Return. The children sneak away into the forest to search for the missing sheep. The trees of the forest awaken and capture them. Tom and Mary follow and find the children in the forest, where they tell stories about the live trees. The trees seem just like ordinary trees to Tom and Mary. Tom, Mary, and the children camp for the night. In the morning, the trees once again come to life and explain that they are now in custody of the Toymaker in Toyland (who is also the Mayor and Chief of Police). Tom, Mary, and the children happily continue on, escorted part of the way by the trees.

Through the windows of the Toymaker's house they watch the Toymaker's brilliant apprentice, Grumio, present a new machine that makes toys without any manual labor. Overjoyed, the Toymaker speeds up the machine to such a high rate that it explodes, destroying every toy in the factory. Tom, Mary, and the children offer to help make more toys in time for Christmas.

Grumio presents another invention, a shrinking "gun" that reduces everyday objects to toy size. He warns that if it is used on anything more than once, the shrunken object disappears completely. The Toymaker is at first delighted at the idea of producing toys by shrinking life-sized objects, but then Tom points out the impossibility of finding enough everyday objects to shrink down into the large quantity of toys needed for Christmas. The Toymaker berates Grumio for his stupidity and throws the shrinking gun out the window in disgust.

Barnaby, who has been spying on them, takes the discarded shrinking gun and uses it to shrink the Toymaker and Tom. When Barnaby's henchmen see him threatening to shoot Tom a second time, they abandon Barnaby. They try to flee, but Barnaby shoots them and locks them up with Tom in a birdcage.

Barnaby forces Mary to marry him by threatening to destroy Tom, and he threatens to destroy the Toymaker if he refuses to preside over the wedding ceremony. While the Toymaker draws out the ceremony, Gonzorgo and Roderigo rescue Tom, and the three of them sneak away and return with an army of toy soldiers to fight Barnaby. Barnaby easily demolishes the toy soldiers with a toy cannon. He is about to obliterate Tom with another dose from the shrinking gun, but Mary destroys it with the toy cannon. The liquid splatters all over Barnaby and shrinks him to toy size. Tom, after challenging Barnaby to a duel with swords, stabs Barnaby, who falls from a great height into an empty toybox.

During the battle with Barnaby, Grumio creates and presents another new invention, one that returns miniaturized people and items to their original size. He immediately uses it on the Toymaker, Gonzorgo, and Roderigo, but not on Barnaby. Grumio is about to use it on Tom, but after reminding Grumio that he is the head toymaker and that Grumio is just his assistant, the Toymaker uses the invention on himself to return Tom to his natural size.

A few days later, Tom and Mary are married attended by all of Mother Goose Village including Gonzorgo and Roderigo as well as the trees from the Forest of No Return, and everyone lives happily ever after.

Cast

[edit]- Ray Bolger as Barnaby

- Tommy Sands as Tom Piper

- Annette Funicello as Mary Contrary

- Ed Wynn as Toymaker

- Tommy Kirk as Grumio

- Kevin Corcoran as Boy Blue

- Henry Calvin as Gonzorgo

- Gene Sheldon as Roderigo

- Mary McCarty – Mother Goose

- Ann Jillian as Bo Peep

- Brian Corcoran as Willie Winkie

- Marilee and Melanie Arnold as Twin 1 and 2

- Jerry Glenn as Simple Simon

- John Perri as Jack-Be-Nimble

- David Pinson as Bobby Shaftoe

- Bryan Russell as The Little Boy

- James Martin as Jack

- Ilana Dowding as Jill

- Robert Banas as Russian Dancer (uncredited)

- Eileen Diamond as Dancer (uncredited)

- Bess Flowers as Villager (uncredited)

- Jeannie Russell as Singer (voice) (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In May 1955, Walt Disney announced that he would produce Babes in Toyland as an animated feature.[6] By October 1956, Disney had assigned Bill Walsh to produce and Sidney Miller to direct the project.[7] However, filming was delayed, and by August 1959, the project was retooled as a live-action television movie, making it Disney's first live-action musical. Ward Kimball had been tapped to produce and direct the project, while Mel Leven would write new lyrics.[8][9]

With Kimball in charge, he reviewed the three scripts that had been written, all of which he found to be "terrible, absolutely nothing." Kimball had found the 1903 operetta script to be too complicated. In his script, he excised the orphans subplot and focused the story on a love triangle between Tom, Mary Contrary, and Barnaby. In the following months, Kimball worked alongside story artist Joe Rinaldi and effects animator Joshua Meador to ensure the film would be visually interesting.[10] In June 1960, Disney told the Los Angeles Times: "We're updating the lyrics; the music, of course, is Victor Herbert's. March of the Toys will be done in animation. I'll be using fantasy with 'live' more and more. I've decided people should play people and shouldn't be animated – only the effects should."[11]

While Disney was vacationing in Europe, Kimball was finalizing set designs and casting decisions, the latter of which required Disney's approval. "We decided on Ray Bolger, things like that, and [such decisions usually] were the provinces of Walt," Kimball later explained. Furthermore, with the studio's option on the film rights set to expire within a year, a studio publicist placed trade advertisements that promoted Kimball's work on the film, leading to Disney deciding that Kimball had got above himself.[12] Kimball was also traveling to New York to scout for Broadway actors to cast in the film. According to Joe Hale, Kimball had wanted one actress for Mary, but Disney had insisted on Annette Funicello. Further casting disagreements led to Kimball being kicked off the film.[13]

In January 1961, Jack Donohue was signed to direct, following his success on Broadway directing Top Banana and Mr. Wonderful, and for his work on TV specials for Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra.[14] While Kimball would still be credited as the screenwriter, he was relegated to directing the 15-minute toy soldier sequence.[15] In March 1961, Disney said he wanted to create a film of the standard of The Wizard of Oz (1939).[2] "It's like a Disney cartoon only with live actors", said one Disney executive.[16]

Casting

[edit]In September 1960, it was reported that Disney had wanted to discuss Dean Jones for the lead role as Tom.[17] By January 1961, Ray Bolger was cast as a villain for the first time in his career.[18] Gene Sheldon, best known for his role of Bernardo in the Spanish Western television series Zorro,[19] appeared alongside his Zorro co-star, Henry Calvin. Tommy Kirk played a supporting role.[20] According to Annette Funicello, Tommy Sands beat out Michael Callan and James Darren to play the male lead.[21]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography started on March 13, 1961, and was scheduled for three months.[2] Preparation, rehearsing and pre-recording took three months.[22] Tommy Kirk said he enjoyed making the film because of the opportunity to work with Ed Wynn:

I thought he was delightful and so did everyone else. You couldn't not like him. He was completely crazy and he was just as crazy offscreen as he was on. But it was all, of course, an act. He was a very serious, religious man in his own way, but he loved playing Ed Wynn, the perfect fool, the complete nut. And he was good at it. Actually I think the movie is sort of a klunker, especially when I compare it to the Laurel and Hardy Babes in Toyland. It's not a great film but it has a few cute moments. It's an oddity. But I'm not embarrassed about it like I am about some other movies I've made.[23]

Funicello had a bad experience with William Fairchild, who had directed her in The Horsemasters (1961), but found Jack Donahue to be "simply wonderful."[22] She also enjoyed the fact "it was the first, and unfortunately, I think, the last time I made a movie in which I actually danced something besides the Watusi or the swim."[24]

Songs

[edit]| Title | Music by | Music adapted by | Lyrics by | Sung by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Mother Goose Village and Lemonade" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns "Mother Goose Village" adapted from musical piece Country Dance "Lemonade" adapted from musical piece Military Ball |

Mel Leven | Chorus |

| "We Won't Be Happy Till We Get It" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns from He Won't Be Happy Till He Gets It |

Mel Leven | Ray Bolger, Henry Calvin and danced by Gene Sheldon |

| "Just a Whisper Away" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns | Mel Leven | Tommy Sands and Annette Funicello |

| "Slowly He Sank to the Bottom of the Sea" | George Bruns | Mel Leven | Henry Calvin & danced by Gene Sheldon | |

| "Castle in Spain" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns | Mel Leven | Ray Bolger (who also dances) |

| "Never Mind, Bo-Peep" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns | Mel Leven | Ann Jillian and chorus |

| "I Can't Do the Sum" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns | Mel Leven | Annette Funicello |

| "Floretta" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns | Mel Leven | Tommy Sands and Chorus |

| "Forest of No Return" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns from The Spider's Den |

Mel Leven | Chorus, Singing trees, and children |

| "Go to Sleep" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns from Go to Sleep, Slumber Deep |

Mel Leven | Tommy Sands, Annette Funicello, and children |

| "Toyland" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns | Mel Leven and Glen MacDonough |

Tommy Sands, Annette Funicello, children and Singing trees |

| "Workshop Song" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns from In The Toymaker's Workshop |

Mel Leven | Ed Wynn, Tommy Sands, Annette Funicello, and children |

| "Just a Toy" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns | Mel Leven | Tommy Sands and Annette Funicello |

| "March of the Toys" | Victor Herbert | Orchestra | ||

| "Tom and Mary" | Victor Herbert | George Bruns from Hail to Christmas |

Mel Leven | Wedding guests |

Release

[edit]In conjunction with the film's release, Babes in Toyland was prominently featured on The Wonderful World of Color television program, with an episode titled "Backstage Party" airing on December 17, 1961.[25][26] It was presented in two parts on The Wonderful World of Disney on December 21 and December 27, 1969.[27] The film was released on DVD on September 3, 2002, by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment.[28] It was released on Blu-ray on December 11, 2012.[29] It was added to the Disney+ subscription service.[30]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Babes in Toyland earned $4.6 million in rentals from the United States and Canada.[3]

Critical response

[edit]A. H. Weiler of The New York Times wrote in his review: "Let us say that Walt Disney's packaging of Victor Herbert's indestructible operetta is a glittering color and song and dance-filled bauble artfully designed for the tastes of the sub-teen set. Adults would have to be awfully young in mind to accept these picture-book caperings of the Mother Goose coterie as stirring stuff. This Toyland is closer to Disneyland, but who ever heard of an adult winning an argument on that issue?"[31] Variety described the film as "an expensive gift, brightly-wrapped and intricately-packaged and is certain to be a fast-selling item in the Yuletide marketplace. A choice attraction for the pre-teen set, it will be an especially big draw among those in the five-to-ten age bracket." However, the review cautioned that older audiences "may be distressed to discover that quaint, charming 'Toyland' has been transformed into a rather gaudy and mechanical 'Fantasyland.' What actually emerged is 'Babes in Disneyland.'"[32]

John L. Scott, reviewing for the Los Angeles Times, felt the film was "considerably more showy than either Herbert's stage original or the first film version done in the middle 30's; and older patrons may resent a loss of quaintness and a surplus of fantasy-whimsy. Nevertheless, the lavish, tinseled picture is a fine, appropriate holiday attraction for all but the sophisticated moviegoer."[33] Harrison's Reports praised the film as "VERY GOOD", and further acknowledged Walt Disney for having "wrapped this one up in gay silk ribbons, beautiful costumes and brilliant splashes of color the envy of the rainbow rangers. Like a tender father, Disney has put this together with the soft sensitivity of a man in whose trust has been placed the dream world of trusting youngsters everywhere."[34] Time wrote Babes in Toyland was "a wonderful piece of entertainment for children under five, but children over five who plan to see it will be well advised to take some Berlitz brushup lessons in baby talk." Additionally, the review was also critical for the modernized music, but praised the March of the Toys sequence.[35]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 36% based on 11 reviews with an average rating of 4.74/10.[36]

Disney's "Babes in Toyland Soldiers"

[edit]Among the most significant legacies of the film has been its influence on Disney's theme parks worldwide. The Babes in Toyland sets were showcased in Disneyland Park as an attraction following the film's release and the Toy Soldiers became an iconic symbol of the holidays at Disneyland, Walt Disney World Resort and other Disney Parks around the world, considered a "draw" and featured heavily in television, online and print advertising rivaling the castles and the famous Disney characters in appearances. Disney's Babes in Toyland Soldiers are the equivalent of the Rockettes' appearance at the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade in that park guests and TV viewers expect to see them every year.

The soldiers also appear in the stop-motion nursery sequence in Walt Disney's 1964 musical fantasy Mary Poppins. They were designed by Disney animator and Imagineer Bill Justice, who with fellow Imagineer X Atencio, created the sequence in the film. Justice designed the park soldiers to match the Babes in Toyland movie soldiers exactly as they appeared in the 1961 film. They made their television debut on Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color when Walt Disney presented the Disneyland Christmas parade in the episode, "Holiday Time at Disneyland."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ "Babes in Toyland (U)". British Board of Film Classification. December 5, 1961. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Becker, Bill (March 23, 1961). "Ed Wynn Returns to a Comedy Role". The New York Times. p. 29.

- ^ a b "All-Time Top Grossers". Variety. January 8, 1964. p. 69.

- ^ Jones, Tom (June 11, 1961). "Disney Live 'Toyland': Victor Herbert Musical Is Re-created In Manufactured Never-Never Land". The New York Times. p. X7.

- ^ Funicello & Romanowski 1994, p. 124.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (May 17, 1955). "Disney's next cartoon film will be 'Babes in Toyland'"". Chicago Daily Tribune. ProQuest 179440596 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (October 20, 1956). "'Babes in Toyland' Will Be Top Disney Musical in 1957". Chicago Daily Tribune. Part I, p. 20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Disney's 1st Live Tuner". Variety. August 25, 1959. p. 22. Retrieved December 21, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Disney 'Babes' to be Live Action TV Musical". The Film Daily. August 28, 1959. p. 9.

- ^ Pierce 2019, p. 223.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (June 25, 1960). "Realist Disney Held His Dreams". Los Angeles Times. Section G, p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pierce 2019, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Didier Ghez, ed. (2011). "Joe Hale". Walt's People – Volume 11: Talking Disney with the Artists who Knew Him. Xlibris. p. 527. ISBN 978-1-465-36840-9.

- ^ "Fox Films Devises Projection Plan: Firm Claims Greater Depth Perception on Wide Screen". The New York Times. January 16, 1961. p. 22.

- ^ Pierce 2019, p. 226.

- ^ Waugh, John C. (April 25, 1961). "'Music Man', 'Flower Drum Song', and 'Babes in Toyland' Face the Camera: Three Musicals in Three Cinematic Styles". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 6.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (September 24, 1960). "McCarey Is Working on Pearl Buck Tale". Chicago Daily Tribune. Part 1, p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (January 16, 1961). "Entertainment: Harvey Will Star in 'Five Finger' Bolger Villain in 'Toyland'; Myrna Fahey in Metro Movie". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tinee, Mae (November 26, 1961). "Gene Sheldon Beats Drums for 'Toyland'". Chicago Daily Tribune. Part 5, p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (September 9, 2019). "The Cinema of Tommy Kirk". Diabolique Magazine.

- ^ Funicello & Romanowski 1994, p. 128.

- ^ a b Funicello & Romanowski 1994, p. 127.

- ^ Kevin (April 1993). "Sex, Lies, and Disney Tape: Walt's Fallen Star". Filmfax. No. 38. p. 70.

- ^ Funicello & Romanowski 1994, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Schumach, Murray (November 7, 1961). "Films by Disney Work Two Ways: Producer Uses the Same Shows for TV and Movies". The New York Times. p. 40.

- ^ "NBC TV AIRS THE WALT DISNEYS ..." D23. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ Donohue, Jack (December 21, 1969), Babes in Toyland: Part 1, The Magical World of Disney, retrieved December 29, 2021

- ^ Babes in Toyland (1.33:1) (DVD). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. September 3, 2002. ASIN B000065V3X. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ Donohue, Jack (December 11, 2012), Babes in Toyland, retrieved December 29, 2021

- ^ "Watch Babes in Toyland | Full movie | Disney+". www.disneyplus.com. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (December 15, 1961). "Disney's 'Babes in Toyland' Is Holiday Show at Music Hall". The New York Times. p. 49. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Babes in Toyland". Variety. Vol. 225, no. 2. December 6, 1961. p. 6. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Scott, John L. (December 21, 1961). ""Babes in Toyland": Bright Yule Package". Los Angeles Times. p. 52. Retrieved April 11, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'Babes in Toyland' with Ray Bolger, Tommy Sands, Annette, Ed Wynn, Tommy Kirk". Harrison's Reports. Vol. 43, no. 47. November 25, 1961. p. 187. Retrieved December 21, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Cinema: Nursery Crhyme". Time. Vol. 78, no. 24. December 15, 1961. p. 85. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "Babes in Toyland (1961)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Bibliography

- Funicello, Annette; Romanowski, Patricia (1994). A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes: My Story. Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-786-88092-8.

- Pierce, Todd James (2019). The Life and Times of Ward Kimball: Maverick of Disney Animation. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-496-82096-9.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Babes in Toyland at IMDb

- Babes in Toyland at the TCM Movie Database

- Babes in Toyland at Rotten Tomatoes

- Babies in Toyland at Disney A to Z

- "A Very Merry Musical: Walt Disney's Babes in Toyland". The History of Disney. December 2011.

- 1961 films

- Babes in Toyland (operetta)

- 1960s musical fantasy films

- 1960s Christmas films

- 1960s coming-of-age films

- 1960s children's fantasy films

- 1960s fantasy adventure films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s American films

- American Christmas films

- American coming-of-age films

- American children's fantasy films

- American fantasy adventure films

- American films with live action and animation

- American musical fantasy films

- Films about toys

- Films about children

- Films directed by Jack Donohue

- Films produced by Walt Disney

- Films scored by George Bruns

- Films using stop-motion animation

- Films about sentient toys

- Films about size change

- Walt Disney Pictures films

- Films set in forests

- Films set in Spain

- English-language musical fantasy films

- English-language adventure films

- English-language Christmas films