Caesarea Maritima

Καισάρεια / قيصرية / קיסריה | |

The ruins of Caesarea Maritima, with the modern resort town of Caesarea (Keisarya) shown in the top right | |

| Location | Caesarea National Park, Hof HaCarmel Regional Council, Israel |

|---|---|

| Region | Sharon plain |

| Coordinates | 32°30′0″N 34°53′30″E / 32.50000°N 34.89167°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Part of | Roman Judea, Syria Palaestina |

| History | |

| Builder | Abdashtart I |

| Founded | 4th century BCE |

| Abandoned | 1265 |

| Periods | Classical antiquity to High Middle Ages |

| Cultures | Phoenician, Roman, Byzantine |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Israel Nature and Parks Authority |

| Public access | Yes |

Caesarea (/ˌsɛzəˈriːə, ˌsɛs-, ˌsiːz-/ SE(E)Z-ə-REE-ə, SESS-; Koinē Greek: Καισάρεια, romanized: Kaisáreia; Hebrew: קֵיסָרְיָה, romanized: Qēsāryā; Arabic: قيسارية, romanized: Qaysāriyyah), also Caesarea Maritima, Caesarea Palaestinae or Caesarea Stratonis,[1][2][a] was an ancient and medieval port city on the coast of the eastern Mediterranean, and later a small fishing village. It was the capital of Roman Judaea, Syria Palaestina and Palaestina Prima, successively, for a period of c. 650 years and a major intellectual hub of the Mediterranean.[3][4] Today, the site is part of the Caesarea National Park, on the western edge of the Sharon plain in Israel.

The site was first settled in the 4th century BCE as a Phoenician colony and trading village known as Straton's Tower[5] after the ruler of Sidon. It was enlarged in the 1st century BCE under Hasmonean rule, becoming a Jewish village;[6] and in 63 BCE, when the Roman Republic annexed the region, it was declared an autonomous city. It was then significantly enlarged in the Roman period by the Judaean client King Herod the Great, who established a harbour and dedicated the town and its port to Caesar Augustus as Caesarea.

During the early Roman period, Caesarea became the seat of the Roman procurators in the region.[7][8] The city was populated throughout the 1st to 6th centuries CE and became an important early centre of Christianity during the Byzantine period. Its importance may have waned following the Muslim conquest of 640 when the city, then known in Arabic as Qisarya (قيسارية), lost its status as provincial capital.[9] After being re-fortified by Muslim rulers in the 11th century, it was conquered by the Crusaders, who strengthened and made it into an important port and was finally slighted by the Mamluks in 1265.

Qisarya was a small fishing village in the early modern period. In February 1948, during the 1948 Palestine war and Nakba, some of its population fled following an attack on a bus by the Zionist militant group Lehi, and the remainder were expelled by the Palmach, who subsequently demolished its houses.[10] The ruins of the ancient city beneath the depopulated village were excavated in the 1950s and 1960s for archaeological purposes.[11]

Name

[edit]Whilst the name Caesarea was frequently used alone for the subject of this article, various markers were used to differentiate the location from these other locations; these include "Palestina" ("of Palestine"),[12] "Maritima" ("by the sea"; Greek: Παράλιος Parálios), "Sebaste" and "Stratonis".[13][14] "Palestina" is the most common term used in ancient sources,[1] but, since the creation of Israel in 1948, historians have tended to use the term less frequently.[2]

The Latin name Caesarea also referred to several other cities in the region, notably Caesarea near Mount Hermon and Caesarea the capital of Cappadocia.

History

[edit]Classical antiquity

[edit]Stratonos pyrgos (Straton's Tower) was founded in the 4th century BCE by Abdashtart I, or Straton I king of Sidon.[6] It was first established as a Phoenician colony and trading village.[5] In 90 BCE, Jewish ruler Alexander Jannaeus captured Straton's Tower as part of his policy of developing the shipbuilding industry and enlarging the Hasmonean kingdom.[6] Straton's Tower remained a Jewish settlement for two more generations, until the area became dominated by the Romans in 63 BCE, when they declared it an autonomous city.[6]

Herodian Caesarea

[edit]

Caesarea was built in Roman Judea under the Jewish client King Herod the Great during c. 22-10/9 BCE near the ruins of the small naval station of Straton's Tower.[6] The site, along with all of Judea, was awarded by Rome to Herod in 30 BCE.[15] The pagan city underwent vast changes under Herod, who renamed it Caesarea in honour of the Roman emperor, Caesar Augustus.[6][12] Caesarea was known as the administrative, economic, and cultural capital of the Judean province from this time.[16]

In 22 BCE, Herod began construction of a deep-sea harbour named Sebastos and built storerooms, markets, wide roads, baths, a temple to the goddess Roma and Emperor Augustus, and imposing public buildings.[17] Herod built his palace on a promontory jutting out into the sea, with a decorative pool surrounded by stoas.[12][15] Every five years, the city hosted major sports competitions, gladiator games, and theatrical productions in its theatre overlooking the Mediterranean Sea.[18]

Sebastos harbor

[edit]Herod built the two jetties of the harbour between 22 and 15 BCE,[19] and in 10/9 BCE he dedicated the city and harbour to Emperor Augustus (sebastos is Greek for augustus).[20] The pace of construction was impressive considering the project's size and complexity.[21] At its height, Sebastos was one of the most impressive harbours of its time. It had been constructed on a coast that had no natural harbours and served as an important commercial harbour in antiquity, rivaling Cleopatra's harbour at Alexandria. Josephus writes: "Although the location was generally unfavorable, [Herod] contended with the difficulties so well that the solidity of the construction could not be overcome by the sea, and its beauty seemed finished off without impediment."[22]

When it was built in the 1st century BCE, the harbour of Sebastos ranked as the largest artificial harbour built in the open sea, enclosing around 100,000 m2.[23][21][24]

The breakwaters were made of lime and pozzolana, a type of volcanic ash, set into an underwater concrete. Herod imported over 24,000 m3 of pozzolana from the name-giving town of Puteoli, today Pozzuoli in Italy, to construct the two breakwaters: the southern one 500 meter, and the northern one 275 meter long.[21] A shipment of this size would have required at least 44 shiploads of 400 tons each.[19] Herod also had 12,000 m3 of local kurkar stone quarried to make rubble and 12,000 m3 of slaked lime mixed with the pozzolana.[25]

Architects had to devise a way to lay the wooden forms for the placement of concrete underwater. One technique was to drive stakes into the ground to make a box and then fill it with pozzolana concrete bit by bit.[21] However, this method required many divers to hammer the planks to the stakes underwater and large quantities of pozzolana were necessary.

Another technique was a double planking method used in the northern breakwater. On land, carpenters would construct a box with beams and frames on the inside and a watertight, double-planked wall on the outside. This double wall was built with a 23 cm (9 in) gap between the inner and outer layer.[26]

Although the box had no bottom, it was buoyant enough to float out to sea because of the watertight space between the inner and outer walls. Once it was floated into position, pozzolana was poured into the gap between the walls and the box would sink into place on the seafloor and be staked down in the corners. The flooded inside area was then filled by divers bit by bit with pozzolana-lime mortar and kurkar rubble until it rose above sea level.[26]

On the southern breakwater, barge construction was used. The southern side of Sebastos was much more exposed than the northern side, requiring sturdier breakwaters. Instead of using the double planked method filled with rubble, the architects sank barges filled with layers of pozzolana concrete and lime sand mortar. The barges were similar to boxes without lids, and were constructed using mortise and tenon joints, the same technique used in ancient boats, to ensure they remained watertight. The barges were ballasted with 0.5 meters of pozzolana concrete and floated out to their position. With alternating layers, pozzolana-based and lime-based concretes were hand-placed inside the barge to sink it and fill it up to the surface.[26]

However, there were underlying problems that led to its demise. Studies of the concrete cores of the moles have shown that the concrete was much weaker than similar pozzolana hydraulic concrete used in ancient Italian ports. For unknown reasons, the pozzolana mortar did not adhere as well to the kurkar rubble as it did to other rubble types used in Italian harbours.[21] Small but numerous holes in some of the cores also indicate that the lime was of poor quality and stripped out of the mixture by strong waves before it could set.[21]

Also, large lumps of lime were found in all five of the cores studied at Caesarea, which shows that the mixture was not mixed thoroughly.[21] However, stability would not have been seriously affected if the harbour had not been constructed over a geological fault line that runs along the coast. Seismic action gradually took its toll on the breakwaters, causing them to tilt down and settle into the seabed.[22] Studies of seabed deposits at Caesarea have shown that a tsunami struck the area sometime during the 1st or 2nd century.[27]

Although it is unknown if this tsunami simply damaged or completely destroyed the harbour, it is known that by the 6th century the harbour was unusable and today the jetties lie more than 5 meters underwater.[28]

Roman Caeserea

[edit]

When Judea became a Roman province in 6 CE, Caesarea replaced Jerusalem as its civilian and military capital and became the official residence of its governors, such as the Roman procurator Antonius Felix, and prefect Pontius Pilatus.[29]

In the third century, Jewish sages exempted the city from Jewish law, or Halakha, as, by this time, the majority of the inhabitants were non-Jewish.[30] The city was chiefly a commercial centre relying on trade.

This city is the location of the 1961 discovery of the Pilate Stone, the only archaeological item that mentions the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, by whose order Jesus was crucified.[31] It is likely Pilate used it as a base, and only went to Jerusalem when needed.[32]

The city was described in detail by the 1st-century Roman Jewish historian Flavius Josephus.[33]

Josephus describes the harbour as being as large as the one at Piraeus, the major harbour of Athens.[23] Remains of the principal buildings erected by Herod as well as the medieval town are still visible today, including the Crusader city, the city walls, the ruined citadel surrounded by the sea, and remains of the cathedral and a second church. Herod's Caesarea grew rapidly, in time becoming the largest city in Judaea, with an estimated population of 125,000 over an urban area of 3.7 square kilometres (1.4 sq mi).

According to Josephus, Caesarea was the scene in 26 CE of a major act of civil disobedience to protest against Pilate's order to plant eagle standards on the Temple Mount of Jerusalem.[34]

Emperor Vespasian raised its status to that of a Colonia, with the name Colonia Prima Flavia Augusta Caesarea.

According to Josephus, the outbreak of the Jewish revolt of 66 CE was provoked by Greeks of a certain merchant house in Caesarea sacrificing birds in front of a local synagogue.[35]

In 70 CE, after the Jewish revolt was suppressed, games were held there to celebrate the victory of Titus. Many Jewish captives were brought to Caesarea; Kasher (1990) claims that 2,500 captives were "slaughtered in gladiatorial games".[36]

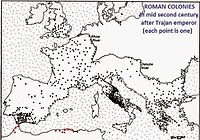

In 6 CE Caesarea became the provincial capital of the Judaea Province, before the change of name to Syria Palaestina in 135, in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba revolt.[37] Caesarea was one of four Roman colonies for veteran Roman soldiers in the Syria-Phoenicia region.[38]

Caesarea is mentioned in the 3rd-century Mosaic of Rehob, with respect to its non-Jewish population.[citation needed]

Early Christian centre

[edit]

According to the Acts of the Apostles, Caesarea was first introduced to Christianity by Philip the Deacon,[39] who later had a house there in which he gave hospitality to Paul the Apostle.[40] It was there that Peter the Apostle came and baptized Cornelius the Centurion and his household, the first time Christian baptism was conferred on Gentiles.[41] When newly converted Paul the Apostle was in danger in Jerusalem, the Christians there accompanied him to Caesarea and sent him off to his native Tarsus.[42] He visited Caesarea between his second and third missionary journeys,[43] and later, as mentioned, stayed several days there with Philip the Deacon. Later still, he was a prisoner there for two years before being sent to Rome.[44]

In the 3rd century, Origen wrote his Hexapla and other exegetical and theological works while living in Caesarea. The Nicene Creed may have originated in Caesarea.

The Apostolic Constitutions says that the first Bishop of Caesarea was Zacchaeus the Publican, followed by Cornelius (possibly Cornelius the Centurion) and Theophilus (possibly the address of the Gospel of Luke).[45]

The first bishops considered historically attested are those mentioned by the early church historian Eusebius of Caesarea, himself a bishop of the see in the 4th century. He speaks of a Theophilus who was bishop in the 10th year of Commodus (c. 189),[46] of a Theoctistus (216–258), a short-lived Domnus and a Theotecnus,[47] and an Agapius (?–306). Among the participants in the Synod of Ancyra in 314 was a bishop of Caesarea named Agricolaus, who may have been the immediate predecessor of Eusebius, who does not mention him, or who may have been bishop of a different Caesarea. The immediate successors of Eusebius were Acacius (340–366) and Gelasius (367–372, 380–395). The latter was ousted by the semi-Arian Euzoius between 373 and 379. Le Quien gives much information about all of these and about later bishops of Caesarea.[48]

The Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem still has a metropolitan see in Caesarea, currently[when?] occupied by metropolitan Basilios Blatsos, since 1975.

The Latin archbishopric of Caesarea in Palestina was made a Roman Catholic titular see in 1432 (Zweder van Culemborg).[49]

The Melkite Catholic Church also considers Caesarea a titular see, with - as of 2013 - Hilarion Capucci holding the title since 1965.[49]

Through Origen and especially the scholarly presbyter Pamphilus of Caesarea, an avid collector of books of Scripture, the theological school of Caesarea won a reputation for having the most extensive ecclesiastical library of the time, containing more than 30,000 manuscripts: Gregory Nazianzus, Basil the Great, Jerome and others came to study there. The Caesarean text-type is recognized by scholars as one of the earliest New Testament types. The collections of the library suffered during the persecutions under the Emperor Diocletian, but were repaired subsequently by bishops of Caesarea.[50] The library was mentioned in 6th-century manuscripts but it may not have survived the capture of Caesarea by the Muslim armies in 640.[51]

Middle Ages

[edit]Byzantine period

[edit]During the Byzantine period, Caesarea became the capital of the new province of Palaestina Prima in 390. As the capital of the province, Caesarea was also the metropolitan see, with ecclesiastical jurisdiction over Jerusalem, when rebuilt after the destruction in the year 70. In 451, however, the Council of Chalcedon established Jerusalem as a patriarchate, with Caesarea as the first of its three subordinate metropolitan sees.

Caesarea remained the provincial capital throughout the 5th and 6th centuries. It fell to Sassanid Persia in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, in 614, and was re-conquered by Byzantium in 625.

Early Muslim period

[edit]

Caesarea was lost for good by the Byzantines to the Muslim conquest in 640. Archaeological excavations discovered a destruction layer connected to the Muslim conquest of the city.[9] Some newer research posits that there was no destruction caused by the Persians in 614 and Muslim Arabs in 640, but rather a gradual economic decline accompanied by the Christian aristocracy fleeing from the city.[56]

According to 9th-century Muslim historian al-Baladhuri (d. 892), the fall of the city was allegedly the result of the betrayal of a certain Yusef, who conducted a party of troops of Muawiyah into the city.[57] The city appears to have been partially destroyed upon its conquest. The 7th-century Coptic bishop John of Nikiû, claims there were "horrors committed in the city of Caesarea in Palestine", while al-Baladhuri merely states that Kaisariyyah/Cæsarea was "reduced",[58] mentioning it as one of ten towns in Jund Filastin (military district of Palestine) conquered by the Muslim Rashidun army under 'Amr ibn al-'As's leadership during the 630s.[59][60][61] After the fall of Caesarea, 4,000 "heads" (captives), men, women and children, were sent to Caliph Umar in Medina, where they were gathered and inspected on the Jurd Plain, a plain commonly used to assemble the troops of Medina before battle, with room for thousands of people, before they were distributed as war booty to slavery in the Rashidun Caliphate.[62]

The former Palaestina Prima was now administered as Jund Filastin, with the capital first at Ludd and then at Ramla.

The city likely remained inhabited for some time under Arab rule, during the seventh and eighth century, albeit with much reduced population. Archaeological evidence shows a clear destruction layer identified with the conquest of 640, followed by some evidence of renewed settlement in the early Umayyad Caliphate.[9] The area remained well farmed from the Rashidun Caliphate through to the First Crusade.[30]

By the 11th century, it appears that the town had once again been developed into a fortified city. Writing in 1047, Nasir Khusraw describes it as "a fine city, with running waters, and palm-gardens, and orange and citron trees. Its walls are strong, and it has an iron gate. There are fountains that gush out within the city".[63][64] This is in agreement with William of Tyre's description of the Crusaders' siege in 1101, mentioning catapults and siege engines used against the city fortifications.[65] Nasir Khusraw noted a "beautiful Friday mosque" in Caesarea in year 1047, "so situated that in its court you may sit and enjoy the view of all that is passing on the sea."[63] This was converted into the church of St. Peter in Crusader times. A wall which may belong to this building has been identified in modern times.[64][66]

Crusader and Ayyubid period

[edit]

Caesarea was taken by Baldwin I in the wake of the First Crusade, in 1101. Baldwin sent a message to emir of Caesarea, demanding him to surrender the city or face a siege, but the Muslims refuse. On May 2, 1101, Baldwin began sieging the city with trebuchets. After fifteen days of resistance, the Crusader army broke through the defenses. Like in Jerusalem in 1099, the Crusaders proceeded to slaughter a portion of the male populace, enslave the women and children and loot the city. Baldwin spared the emir and qadi for a hefty ransom. Baldwin appointed a cleric veteran of the First Crusade, also named Baldwin, as the new Latin archbishop of Caesarea.[67]

It was under Crusader control between 1101 and 1187 and again between 1191 and 1265.[68]

William of Tyre (10.15) describes the use of catapults and siege towers, and states that the city was taken in an assault after fifteen days of siege and given over to looting and pillaging. Syriac Orthodox patriarch Michael the Syrian (born ca. 1126) records that the city was "devastated upon its capture".[69]

William of Tyre mentions (10.16) the discovery of a "vessel of the most green colour, in the shape of a serving dish" (vas coloris viridissimi, in modum parapsidis formatum) which the Genuese thought to be made of emerald, and accepted as their share of the spoils. This refers to the hexagonal bowl known as the Sacro Catino in Italian, which was brought to Genoa by Guglielmo Embriaco and was later identified as the Holy Chalice.[70]

Caesarea was incorporated as a lordship (dominion) within the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the Latin See of Caesarea was established, with ten archbishops listed for the period 1101–1266 (treated as titular see from 1432–1967). Archbishop Heraclius attended the Third Lateran Council in 1179.

Saladin retook the city in 1187, but it was once again captured by the Crusaders during the Third Crusade in 1191. In 1251, Louis IX of France fortified the city, ordering the construction of high walls (parts of which are still standing) and a deep moat.[71]

The Arab geographer Yaqut, writing in the 1220s, named Kaisariyyah as one of the principal towns in Filastîn (Palestine).[72]

The city was finally recovered in 1265, when it was reconquered by the Mamluk armies of Sultan Baibars, who ordered his troops to scale the walls in several places simultaneously, enabling them to penetrate the city.[73] Baibars destroyed the fortified city completely to prevent its re-emergence as a Crusader stronghold, in line with the Mamluk practice in other formerly-Crusader coastal cities.[74][75][76]

During the Mamluk period, the ruins of ancient Caesarea and of the Crusader fortified town lay uninhabited.[73]

Al-Dimashqi, writing around 1300, noted that Kaisariyyah belonged to the Kingdom of Ghazza (Gaza).

Modern period

[edit]Early Ottoman

[edit]Caesarea became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1516, along with the rest of the Levant, and remained under Ottoman rule for four centuries.

In 1664, a settlement is mentioned consisting of 100 Moroccan families, and 7–8 Jewish ones.[77] In the 18th century it again declined.[78]

In 1806, the German explorer Seetzen saw "Káisserérie" as a ruin occupied by some poor fishermen and their families.[79]

Late Ottoman

[edit]In 1870, Victor Guérin visited the site.[80] The village of Qisarya (Arabic: قيسارية) was allocated in 1880 to Bushnak (Bosniak) immigrants from Bosnia.[81] The Bosniaks had emigrated to the area after Ottoman Bosnia was occupied by Austria-Hungary in 1878. According to historian Roy Marom,

Fifty families of Bosnian refugees, mostly from Mostar, the main urban center of Bosnia and Herzegovina, settled among the ruins of Caesarea, renaming it with the Arabic name of Qisarya. Using the ancient masonry found on site, the settlers constructed a modern town with spacious accommodations and broad intersecting streets, according to traditional Bosnian town-plans. The town had two mosques, a caravanserai, a marketplace, a residence for the mudir, a harbor and custom offices. Qisarya attracted high-ranking Bosnian functionaries who established estates near Qisarya. The town was declared the seat of a mudirieh (a minor administrative division).[82]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Caesarea had 670 inhabitants, in addition to 265 Muslim inhabitants, who were noted as "Bosniaks".[83]

Petersen, visiting the place in 1992, noted that the nineteenth-century houses were built in blocks, generally one story high (with the exception of the house of the governor.) Some houses on the western side of the village, near the sea, have survived. There were a number of mosques in the village in the nineteenth century, but only one ("The Bosnian mosque") has survived. This mosque, located at the southern end of the city, next to the harbour, is described as a simple stone building with a red-tiled roof and a cylindrical minaret. In 1992 it was used as a restaurant and as a gift shop.[66]

British Mandate of Palestine

[edit]Qisarya

قيسارية Qisarya | |

|---|---|

Village | |

The Bosnian Mosque at Qisarya | |

| Palestine grid | 140/212 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Haifa |

| Date of depopulation | February 1948[84] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 31,786 dunams (31.786 km2 or 12.273 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 960 |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Expulsion by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Caesarea |

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Caesarea had a population of 346; 288 Muslims, 32 Christians and 26 Jews,[87] where the Christians were 6 Orthodox, 3 Syrian Orthodox, 3 Roman Catholics, 4 Melkites, 2 Syrian Catholics and 14 Maronite.[88] The population had increased in the 1931 census to 706; 19 Christians, 4 Druse and 683 Muslims, in a total of 143 houses.[89]

A Jewish settlement, Kibbutz Sdot Yam, was established 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) south of the Muslim town in 1940.

The Muslim village declined in economic importance and many of Qisarya's Muslim inhabitants left in the mid-1940s, when the British extended the Palestine Railways which bypassed the shallow-draft port. Qisarya had a population of 960 in 1945 statistics,[86] with Qisarya's population composition 930 Muslims and 30 Christians in 1945.[85][86] In 1944/45 a total of 18 dunums of Muslim village land was used for citrus and bananas, 1,020 dunums were used for cereals, while 108 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[90][91] while 111 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[92]

-

Caesarea 1947

-

Caesarea 1947

-

Caesarea 1942 1:20,000

-

Caesarea 1945 1:250,000

1947–present

[edit]The civil war in Mandatory Palestine began on 30 November 1947. In December 1947 a village notable, Tawfiq Kadkuda, approached local Jews in an effort to establish a non-belligerency agreement.[93] The 31 January 1948 Lehi attack on a bus leaving Qisarya, which killed two and injured six people, precipitated an evacuation of most of the population, who fled to nearby al-Tantura.[94] The Haganah then occupied the village because the land was owned by the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association and, fearing that the British would force them to leave, decided to demolish the houses.[94][10] This was done on 19–20 February, after the remaining residents were expelled and the houses were looted.[94] According to Benny Morris, the expulsion of the population had more to do with illegal Jewish immigration than the ongoing civil war.[95] In the same month the 'Arab al Sufsafi and Saidun Bedouin, who inhabited the dunes between Qisarya and Pardes left the area.[96]

In 1952, the Jewish town of Caesarea was established 1–2 kilometres (0.62–1.24 mi) to the north of the ruins of the old city, which in 2011 were incorporated into the newly created Caesarea National Park.

In 1992, Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi described the village remains: "Most of the houses have been demolished. The site has been excavated in recent years, largely by Italian, American, and Israeli teams, and turned into a tourist area. Most of the few remaining houses are now restaurants, and the village mosque has been converted into a bar."[97]

Archaeology and reconstruction

[edit]Large-scale archaeological excavations began in the 1950s and 1960s and continue to this day, conducted by volunteers working under the supervision of archaeologists. The majority of the archaeological excavations are done by the United States and Israel.[98]

Remains from many periods have been uncovered, in particular from the large city of the Roman and Byzantine periods, and from the fortified town of the Crusaders. Major Classical-era findings are the Roman theatre; a temple dedicated to the goddess Roma and Emperor Augustus; a hippodrome rebuilt in the 2nd century as a more conventional theatre;[dubious – discuss] the Tiberieum, where archaeologists found a reused limestone block with a dedicatory inscription mentioning Pilate[31] the only archaeological find bearing his name and title; a double aqueduct that brought water from springs at the foot of Mount Carmel; a boundary wall; and a 200 ft (60 m) wide moat protecting the harbour to the south and west.

In 1986, the Israel Exploration Society published the archaeological findings of L.I. Levine and E. Netzer, during three seasons of excavations (1975, 1976 and 1979) at Caesarea.[99] In 2010, archaeological surveys-excavations of the site were conducted by Dani Vaynberger and Carmit Gur on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA),[100] and others by Peter Gendelman and Jacob Sharvit on behalf of the IAA, Yosef Porath, Beverly Goodman, and Michal Artzy on behalf of University of Haifa.[101] The site continued to be excavated as late as 2013.[102] A new phase of exploration began in 2018 under the direction of Joseph L. Rife, Phillip Lieberman, and Peter Gendelman on behalf of Vanderbilt University and the IAA.

In February 2015, marine archaeologists and diving club members from the Israel Antiquities Authority announced that about 2,000 gold coins dating back more than 1,000 years have been discovered. According to the researchers, this could be a large merchant ship trading with the coastal cities and ports in the Mediterranean and the coins could be for paying the salaries of the Fatimid military garrison. The remains are now the property of the state.[103] In January 2021, researchers re-examined the coins discovered in 2015 and they retrieved hundreds more. The coins with Arabic text on both sides were 24 carat gold and 95 percent purity.[104]

Roman and Byzantine administrative palace

[edit]A large compound, located in the archaeologists' Area CC, in the first insula of the Roman and Byzantine city south of the Crusader wall and close to the sea, along the decumanus, was in use as the Roman praetorium of the equestrian fiscal procurator, and then became the seat of the Byzantine governor.[105] It contained a basilica with an apse, where magistrates would have sat, for the structure was used as a hall of justice, as fragments of inscriptions detailing the fees that court clerks might claim attest.[citation needed]

Roman mosaic (2nd–3rd c. CE)

[edit]A rare, colorful mosaic dating from the 2nd-3rd century CE was uncovered in 2018, in the Caesarea National Park near a Crusader bridge. It contains the image of three male figures wearing togas, geometric patterns, as well as a largely damaged inscription in Greek. It is one of the few extant examples of mosaics from that specific time period in Israel. The mosaic measures 3.5 × 8 meters and is, according to its excavators, "of a rare high quality" comparable to that of Israel's finest examples.[106]

Hebrew priestly courses inscription (3rd–4th c. CE)

[edit]In 1962, a team of Israeli and American archaeologists discovered in the sand of Caesarea three small fragments of one Hebrew stone inscription bearing the partial names of places associated with the priestly courses (the rest of which had been reconstructed), dated to the third-fourth centuries. The uniqueness of this discovery is that it shows the places of residence in Galilee of the priestly courses, places presumably resettled by Jews after the First Jewish–Roman War under Hadrian.[107][108][109][110]

Byzantine martyrion church

[edit]The main Byzantine church, an octagonal martyrion, was built in the 6th century and sited directly upon the podium that had supported Herod's temple, as was a widespread Christian practice. The martyrion was richly paved and surrounded by small radiating enclosures. Archaeologists have recovered some foliate capitals that included representations of the Cross. The site would in time be re-occupied, this time by a mosque.

6th-century gold glass mosaic table

[edit]In 2005 excavators found a well-preserved 6th-century panel covered in an exquisite mosaic made of glass gold and coloured opaque glass tesserae, used as a table, patterned with crosses and rosettes.[111][112]

Early-12th-century Muslim hoard

[edit]In 2018, a significant hoard of 24 gold coins and a gold earring was unearthed and tentatively dated to 1101.[113]

UNESCO status

[edit]Since 2000, the site of Caesarea is included in the "Tentative List of World Heritage Places" of the UNESCO.[15]

See also

[edit]- Martyrs of Palestine, book by Eusebius recounting the story of Christian martyrs executed in Caesarea

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ While the name Caesarea was frequently used alone, various suffixes were also used to disambiguate it from the other cities in the Roman Empire that were also known as Caesarea. Caesarea-Palaestinae was the most common of these in the ancient texts, but fell out of use in contemporary academic literature in favor of Caesarea Maritima.[1][2]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Raban, Avner; Holum, Kenneth G. (1996). Caesarea Maritima : a retrospective after two millennia. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. xxviii. ISBN 90-04-10378-3. OCLC 34557572.

Caesarea Maritima, more commonly Caesarea Palestine in the ancient texts, was a foundation of Herod the Great. [Footnote: Also Caesarea Stratonis, etc.; see I. Benzinger, RE 4 (1894), s.v. Caesarea (10), 1291-92.]

- ^ a b c Masalha, N. (2018). Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History. Zed Books. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1-78699-275-8.

The capital of Byzantine Palestine and of Palaestina Prima was Caesarea-Palaestina, 'Caesarea of Palestine' (von Suchem 1971: 7, 111; 2013; Gilman et al. 1905). This city was also called 'Caesarea by the Sea', or Caesarea Maritima. Since the creation of Israel in 1948 historians in the West have tended to avoid referring to the historic name of the Palestinian city, Caesarea-Palaestina, and use only the name Caesarea Maritima.

- ^ Rabbān, A.; Holum, K.G. (1996). Caesarea Maritima: A Retrospective After Two Millennia. Documenta et monumenta orientis antiqui / Documenta et monumenta orientis antiqui. E.J.Brill. p. 578. ISBN 978-90-04-10378-8.

As the city was the capital first of all Palestine , then of Palaestina Prima , the άpxov and his officium resided there

- ^ Prawer, J.; Ben-Shammai, H. (1996). The History of Jerusalem: The Early Muslim Period (638-1099). NYU Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8147-6639-2. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

…Caesarea, not Jerusalem, was the provincial administrative capital. Denying any further administrative status to Caesarea, the Muslims transferred the center of provincial administration first to Lod and then to Ramla…

- ^ a b Evans, Craig A. (14 January 2014). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 9781317722243 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Duane W. Roller; Robert L. Hohlfelder (1983). "The Problem of the Location of Straton's Tower". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (252): 61–68. doi:10.2307/1356838. JSTOR 1356838. S2CID 163628792.

- ^ "Founded in the years 22-10 or 9 B.C. by Herod the Great, close to the ruins of a small Phoenician naval station named Strato's Tower (Stratonos Pyrgos, Turns Stratonis), which flourished during the 3d to 1st c. B.C. This small harbor was situated on the N part of the site. Herod dedicated the new town and its port (limen Sebastos) to Caesar Augustus. During the Early Roman period, Caesarea was the seat of the Roman procurators of the province of Judea. Vespasian, proclaimed emperor at Caesarea, raised it to the rank of Colonia Prima Flavia Augusta, and later Alexander Severus raised it to the rank of Metropolis Provinciae Syriae Palestinae." A. Negev, "CAESAREA MARITIMA Palestine, Israel" in: Richard Stillwell et al. (eds.), The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites (1976).

- ^ Isaac, B.H., The Near East Under Roman Rule: Selected Papers (Brill, 1997), p. 15

- ^ a b c Archaeological literature in the 1970s seemed to favour complete abandonment in the 7th century, but this view has been corrected with further excavations in the 1980s. See Inge Lyse Hansen; Chris Wickham, eds. (2000). The Long Eighth Century. BRILL. pp. 292–. ISBN 978-90-04-11723-5. OCLC 1013307862., footnote 49.

- ^ a b Morris 2004, p. 129-130: "As we have seen, Haganah policy until the end of March was non-expulsive. But there were one or two local, unauthorised initiatives… And there was one authorised expulsion. The inhabitants of Qisarya, south of Haifa, lived and cultivated Jewish (PICA) and Greek Orthodox church lands. One leading family evacuated the village on 10 January. Most of the population left – apparently for neighbouring Tantura – immediately after the 31 January LHI ambush of a bus that had just pulled out of Qisarya in which two Arabs died and eight were injured (one of the dead and several injured were from the village). The Haganah decided to occupy the site because the land was PICA-owned. But after moving in, the Haganah feared that the British might eject them. The commanders asked headquarters for permission to level the village. Yitzhak Rabin, the Palmah’s head of operations, opposed the destruction – but he was overruled. On 19–20 February, the Palmah’s Fourth Battalion demolished the houses. The 20-odd inhabitants who were found at the site were moved to safety and some of the troops looted the abandoned homes. A month later, the Arabs were still complaining to local Jewish mukhtars that their stolen money and valuables had not been returned. The Qisarya Arabs, according to Aharon Cohen, had ‘done all in their power to keep the peace . . . The villagers had supplied agricultural produce to Jewish Haifa and Hadera . . . The attack was perceived in Qisarya – and not only there – as an attempt by the Jews to force them (the Arabs) living in the Jewish area, to leave . . .’”

- ^ Raban and Holum, 1996, p. 54

- ^ a b c Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ Sharon, M. (2021). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Volume Two: -B-C-. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1 The Near and Middle East (in Latin). Brill. p. 247. ISBN 978-90-04-47004-0. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Schwartz, D.R. (1992). Studies in the Jewish Background of Christianity. WissUNT Neuen Testament Series. J.C.B. Mohr. p. 171. ISBN 978-3-16-145798-2. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

i) Josephus, in his most formal reference to Caesarea Maritima, calls in "Caesarea Sebaste" (Ant. 16.136); i) Philo, in his only reference to Caesarea Maritima, calls it "Caesarea . . . surnamed Sebaste" (Leg. 305); and iii) both Josephus and the New Testament, as noted above (n. 9), frequently call Caesarea Maritima plain "Caesarea," which shows it is comparable to "Frankfurt" and not to "York."

- ^ a b c "In the year 30 BCE the (Phoenician) village was awarded to Herod, who built a large port city at the site, and called it "Caesarea" in honor of his patron Octavian Augustus Caesar....The city transformed rapidly into a great commercial centre, and by the year 6 BCE became the headquarters of the Roman government in Palestine. Since Caesarea had no rivers or springs, drinking water for the prospering Roman and Byzantine city was brought via a unique high-level aqueduct, originating at the nearby Shuni springs, some 7.5 km northeast of Caesarea. [...] Caesarea served as a base for the Roman legions who quelled the Great Revolt that erupted in 66 BCE [sic], and it was here that their commanding general Vespasian was declared Caesar. After the destruction of Jerusalem, Caesarea became the most important city in the country: Pagans, Samaritans, Jews and Christians lived here in the third and fourth centuries CE.UNESCO tentative list:Caesarea

- ^ Masalha, Nur (2018). Palestine : a four thousand year history. London. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-78699-272-7. OCLC 1046449706.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Crossan, 1999, p. 232

- ^ Hohlfelder, Robert L. "Caesarea". Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary. 1: 800.

- ^ a b Votruba, G., 2007, Imported building materials of Sebastos Harbour, Israel, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 36: 325-335.

- ^ Raban, A., 1992. Sebastos: the royal harbour at Caesarea Maritima - a short-lived giant, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 21: 111-124.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hohlfelder, R. 2007. "Constructing the Harbour of Caesarea Palaestina, Israel: New Evidence from ROMACONS Field Campaign of October 2005". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 36:409-415.

- ^ a b Holum, K. 1988. King Herod's Dream: Caesarea on the Sea. New York: Norton.

- ^ a b George Menachery, 1987 in Kodungallur, City of St. Thomas, Azhikode, 1987, Chapter II note 19 quotes the National Geographic article: Robert L. Hohlfelder, "Caesarea Maritima, Herod the Great's City on the Sea". The National Geographic, 171/2, February 1987, pp. 260-79.

2000 years ago, Caesarea Maritima welcomed ships to its harbour called Sebastos. Featuring innovative design and hydraulic concrete, this building feat set a standard for harbours to come. A monumental work, city and harbour were constructed on an unstable storm-battered shore, at a site lacking a protective cape or bay. The project challenged Rome's most skilled engineers. Hydraulic concrete blocks, some weighing 50 short tons (45 t) anchored the north breakwater of the artificial harbour ... Caesarea Maritima, rival to Alexandria in the Eastern trade, a city worthy to be named for Herod's patron, Caesar Augustus, master of the Roman world, in view of its opulence and magnificence. - ^ Votruba, G. 2007. "Imported Building Materials of Sebastos Harbour, Israel." International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 36:325-335.

- ^ Porath, Yosef; Epstein, Mindi; Friedman, Zaraza; Michaeli, Talila (2013). Hurowitz, Ann Roshwalb (ed.). Caesarea Maritima I: Herod's circus and related buildings Part 1: Architecture and stratigraphy. Vol. 53. Israel Antiquities Authority. ISBN 978-965-406-379-1. JSTOR j.ctt1fzhdc0.

- ^ a b c Brandon, C., 1996, Cements, Concrete, and Settling Barges at Sebastos: Comparisons with Other Roman Harbor Examples and the Descriptions of Vitruvius, Caesarea Maritima: A Retrospective after Two Millennia, 25-40.

- ^ Reinhardt, E., Goodman, B., Boyce, J., Lopez, G., Hengstum, P., Rink, W., Mart, Y., Raban, A. 2006. "The Tsunami of 13 December A.D. 115 and the Destruction of Herod the Great's Harbor at Caesarea Maritima, Israel." Geology 34:1061-1064.

- ^ Raban, A., 1992, Sebastos: the royal harbour at Caesarea Maritima - a short-lived giant, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 21: 111-124.

- ^ A History of the Jewish People, H. H. Ben-Sasson editor, 1976, page 247: "When Judea was converted into a Roman province [in 6 CE, page 246], Jerusalem ceased to be the administrative capital of the country. The Romans moved the governmental residence and military headquarters to Caesarea. The centre of government was thus removed from Jerusalem, and the administration became increasingly based on inhabitants of the Hellenistic cities (Sebaste, Caesarea and others)."

- ^ a b Safrai, 1994, p. 374

- ^ a b Reed, Jonathan L. (2002). Archaeology and the Galilean Jesus: a re-examination of the evidence. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-56338-394-6. p. 18. Studying the historical Jesus: evaluations of the state of current research by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998; ISBN 90-04-11142-5, pg. 65

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Jesus by Daniel J. Harrington, 2010; ISBN 0-8108-7667-1, pg. 32

- ^ Jewish Antiquities XV.331ff; The Jewish War, I.408ff

- ^ Antiquities of the Jews XVII:III:1,2,3. The Jewish War II:IX:3.

- ^ Josephus. BJ. 2.14.5., Perseus Project BJ2.14.5, .

- ^ Kasher, Aryeh (1990) Jews and Hellenistic Cities in Eretz-Israel: Relations of the Jews in Eretz-Israel with the Hellenistic Cities During the Second Temple Period (332 BCE-70CE), Mohr Siebeck; ISBN 3-16-145241-0, pg. 311

- ^ Shimon Applebaum (1989) Judaea in Hellenistic and Roman Times: Historical and Archaeological Essays, Brill Archive; ISBN 90-04-08821-0, pg. 123

- ^ Butcher, Kevin (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-08-92-36715-3. p. 230

- ^ Acts 8:40

- ^ Acts 21:8–10

- ^ Acts 10:1–11:18

- ^ Acts 9:30

- ^ 18:22

- ^ Acts 23:23, 25:1-13

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Apostolic Constitutions, Book VII". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ Church History V,22

- ^ Church History VII,14

- ^ Le Quien, Michel (1740). Oriens Christianus, in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus: quo exhibentur ecclesiæ, patriarchæ, cæterique præsules totius Orientis. Tomus tertius, Ecclesiam Maronitarum, Patriarchatum Hierosolymitanum, & quotquot fuerunt Ritûs Latini tam Patriarchæ quàm inferiores Præsules in quatuor Patriarchatibus & in Oriente universo, complectens (in Latin). Paris: Ex Typographia Regia. coll. 529-574, 1285-1290. OCLC 955922748.

- ^ a b Annuario Pontificio 2013. Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013, p. 867. ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1.

- ^ Jerome, "Epistles" xxxiv

- ^ Swete, Henry Barclay. Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, pp 74-75.

- ^ Barber, Richard (2004). The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief. Harvard University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-674-01390-2. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Abbé Mariti [in Italian] (1792). Travels through Cyprus, Syria, and Palestine: with a General History of the Levant. Vol. I. Dublin: Printed for P. Byrne. pp. 399–400. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Marica, Patrizia (2000). Museo del Tesoro, San Lorenzo. Genoa, Italy: sagep. pp. 7–12. ISBN 9788870589795.

- ^ Wood, Juliette (2012). The Holy Grail: History and Legend (2 ed.). University of Wales Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780708326268. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ Holum, Kenneth G. (May 1992). "Archaeological Evidence for the Fall of Byzantine Caesarea". BASOR. 286 (286). The University of Chicago Press: 73–85. doi:10.2307/1357119. JSTOR 1357119. S2CID 163306127. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Meyers, Eric M. (1999). ""The Fall of Caesarea Maritima"". Galilee Through the Centuries. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060408. 380ff.

- ^ Meyers, 1999, p. 381. (The origins of the Islamic state trans. Philip Khuri Hitti, 1916). The archaeological stratum representing the destruction is analyzed in Cherie Joyce Lentzen, The Byzantine/Islamic Occupation of Caesarea Maritima as Evidenced Through the Pottery (Drew University 1983), noted by Meyer 1999:381 note 23. See also: Al-Baladhuri, 1916, pp. 216-219.

- ^ The conquered towns included "Ghazzah (Gaza), Sabastiyah (Samaria), Nabulus (Shechem), Cæsarea, Ludd (Lydda), Yubna, Amwas (Emmaus), Yafa (Joppa), Rafah, and Bayt Jibrin. (Bil. 138), quoted in Le Strange, 1890, p.28

- ^ Al-Baladhuri, 1916, pp. 216-219

- ^ Meyers, 1999, p. 380

- ^ Dynamics in the History of Religions Between Asia and Europe: Encounters, Notions, and Comparative Perspectives. (2012). Nederländerna: Brill. p. 180-181

- ^ a b Le Strange, Guy, 1890, p. 474

- ^ a b Denys Pringle; Professor Denys Pringle (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus: Volume 1, A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). Cambridge University Press. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-0-521-39036-1. OCLC 1008255454.

- ^ William of Tyre, Historia 10.15.

- ^ a b Petersen, 2001, pp. 129-130

- ^ The Crusades by Thomas Asbridge, pg. 123-124.

- ^ Pringle, 1997, pp. 43-45

- ^ Meyers (1999:381).

- ^ Marica, Patrizia, Museo del Tesoro Genoa, Italy (2007), 7–12. The Sacro Catino is a hexagonal bowl made from Roma-era green glass, some 9 cm high and 33 cm across. It was seized and taken to Paris by Napoleon in 1805, and it was damaged when it was returned to Genoa in 1816. The object was not immediately identified as the Holy Grail. William of Tyre states that was still claimed to be made of emerald by the Genoese in his day, some 70 years later, the implication being that emerald was thought to have miraculous properties of their own in medieval lore (Unde et usque hodie transeuntibus per eos magnatibus, vas idem quasi pro miraculo solent ostendere, persuadentes quod vere sit, id quod color esse indicat, smaragdus.) The first explicit claim identifying the bowl with the Holy Grail (the vessel used in the Last Supper) is found in the Chronicon by Jacobus de Voragine, written in the 1290s. Juliette Wood, The Holy Grail: History and Legend (2012).

- ^ "Caesarea Maritima - Madain Project (en)". madainproject.com. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 29

- ^ a b Kenneth G. Holum, "The Archaeology of Caesarea Maritima", in Bart Wagemakers, ed., Archaeology in the 'Land of Tells and Ruins': A History of Excavations in the Holy Land Inspired by the Photographs and Accounts of Leo Boer (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2014), 182-201. ISBN 9781782972457

- ^ D. Sivan; et al. (11 February 2004). "Ancient coastal wells of Caesarea Maritima, Israel, an indicator for relative sea level changes during the last 2000 years" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 222 (1). Elsevier: 318. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.222..315S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.02.007.

- ^ "Caesarea- from Roman City to Crusader Fortress". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ Möhring, Hannes (2009). "Die muslimische Strategie der Schleifung fränkischer Festungen und Städte in der Levante". Burgen und Schlösser - Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege (in German). 50 (4): 216. doi:10.11588/BUS.2009.4.48565.

- ^ Roger, 1664; cited in Ringel 1975, 174; cited in Petersen, 2001, p.129

- ^ Petersen, 2001, p. 129

- ^ Seetzen, 1854, vol 2, pp. 72–73. Alt: Seetzen, Ulrich Jasper: Ulrich Jasper Seetzen's Reisen durch Syrien. p. 80

- ^ Guérin, 1875, pp. 321–339

- ^ Oliphant, 1887, p. 182

- ^ Marom, Roy (9 March 2023). "Hadera: transnational migrations from Eastern Europe to Ottoman Palestine and the glocal origins of the Zionist-Arab conflict". Middle Eastern Studies. 60 (2): 250–270. doi:10.1080/00263206.2023.2183499. ISSN 0026-3206. S2CID 257443159.

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 181

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xviii, village #177. Also gives the cause for depopulation

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 49

- ^ a b c Department of Statistics, 1945, p.14

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Haifa, p. 34

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 49

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 95

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 183

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 91

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 141

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 92

- ^ a b c Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny Morris; Benny Morris; Morris Benny (2004). Charles Tripp (ed.). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6. OCLC 1025810122.

- ^ Morris, 2008, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny Morris; Benny Morris; Morris Benny (2004). Charles Tripp (ed.). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6. OCLC 1025810122.

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p.184

- ^ "A Museum Renders Unto Caesarea". L.A.'s Natural History Museum. 4 September 1988. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "Society Biblical Archaeology | Israel Exploration Society | החברה לחקירות ארץ ישראל". Israel Exploration Society.

- ^ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2010, Survey Permit # A-5817

- ^ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2010, Survey Permit # A-5949, Survey Permit # G-10, and Survey Permit # G-25

- ^ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2013, Survey Permit # A-6743

- ^ "Israeli divers chance upon 'priceless' treasure on seabed". BBC News. 18 February 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Bradley, Charlie (15 January 2021). "Archaeology breakthrough: Shipwreck treasure 'so valuable it's priceless' found in Israel". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Patrich, Joseph (2008). "A Government Compound in Roman-Byzantine Caesarea". The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (NEAEHL). Vol. 5. pp. 1668–1680.

- ^ "Rare Greek inscription and colorful 1,800-year-old mosaic uncovered at Caesarea". www.timesofisrael.com.

- ^ Avi-Yonah, Michael (1962). "A List of Priestly Courses from Caesarea". Israel Exploration Journal. 12 (2): 137–139. JSTOR 27924896.

- ^ Avi-Yonah, Michael (1964). "The Caesarea Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. L.A. Mayer Memorial Volume (1895-1959): 24–28. JSTOR 23614642. (Hebrew)

- ^ Samuel Klein, Barajta der vierundzwanzig Priester Abteilungen (Baraitta of the Twenty-Four Priestly Divisions), in: Beiträge zur Geographie und Geschichte Galiläas, Leipzig 1909

- ^ Vardaman, E. Jerry and Garrett, J.L., The Teacher's Yoke, Waco TX 1964

- ^ Unique glass mosaic unveiled after restoration in Caesarea, Haaretz, The Associated Press and Nadav Shragai, 28 January 2008, accessed 23 June 2019

- ^ Haaretz, picture of the glass mosaic panel, accessed 23 June 2019

- ^ Rare gold coins found in Israeli city of Caesarea. BBC News, 3 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018

Sources

[edit]- Abu Shama (d. 1268) (1969): Livre des deux jardins ("The Book of Two Gardens"). Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Cited in Petersen (2001).

- Ad, Uzi (9 May 2007). "Caesarea, the High Aqueduct in Nahal 'Ada". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (119).

- Avner, Rita; Gendelman, Peter (30 January 2007). "Caesarea". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (119).

- Barber, Richard W. (2004). The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674013905.

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C. R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 12-29, 34)

- Crossan, J. D. (1999). Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Christ. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-567-08668-2.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Gendelman, Peter (24 July 2011). "Caesarea". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (123).

- Gendelman, Peter; Massarwa, Abdallah (15 August 2011). "Caesarea, Sand Dunes (South)". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (123).

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description géographique, historique et archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hitti, Philip Khûri (1916). The Origins of the Islamic State: Being a Translation from the Arabic, Accompanied with Annotations, Geographic and Historic Notes of the Kitâb Fitûh al-Buldân of al-Imâm abu-l Abbâs Ahmad ibn-Jâbir al-Balâdhuri. New York: Columbia University.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Levine, Lee I. (1975). Caesarea Under Roman Rule. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-04013-7.

- Mariti, Giovanni (1792). Travels Through Cyprus, Syria, and Palestine: With a General History of the Levant. Vol. 1. Dublin: P. Byrne. (p. 396 ff)

- Meyers, E. M. (1999). ""The Fall of Caesarea Maritima"". Galilee Through the Centuries. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 157506040X.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931: Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Morris, B. (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9.

- Oliphant, L. (1887). Haifa; or, Life in Modern Palestine.

- Oren, Eliran (1 June 2010). "Caesarea". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (122).

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R.E. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine. British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Porat, Yosef (31 May 2004). "Caesarea". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (116).

- Pringle, D. (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A–K (Excluding Acre and Jerusalem). Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39036-2.

- Pringle, D. (1997). Secular Buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: An Archaeological Gazetteer. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-46010-7.

- Ringel, Joseph (1975). Césarée de Palestine: étude historique et archéologique (in French). Éditions Ophrys, University of California. ISBN 9782708004146.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the Year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (p. 44)

- Safrai, Z. (1994). The Economy of Roman Palestine. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10243-X.

- Sa‘id, Kareem (22 May 2006). "Caesarea". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (116).

- Sa‘id, Kareem (10 July 2007). "Caesarea". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (119).

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population List of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Seetzen, U. J. (1854). Ulrich Jasper Seetzen's Reisen durch Syrien, Palästina, Phönicien, die Transjordan-länder, Arabia Petraea und Unter-Aegypten (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin: G. Reimer.

- Sharon, M. (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, B–C. Vol. 2. Brill. ISBN 90-04-11083-6. (Sharon, 1999, pp. 252)

- al-'Ulaymi (1876). Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C.: Fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn. Trans. Henry Sauvaire. p. 80–81

- Joseph Patrich, "Caesarea in the Time of Eusebius" in S. Inowlocki, C. Zemagni (eds.), Reconsidering Eusebius: Collected papers on literary, historical, and theological issues (2011), 1–24.

- Lehmann, Clayton Miles; Holum, Kenneth G. (2002). The Greek and Latin Inscriptions of Caesarea Maritima. University of Michigan. ISBN 9780897570282.

- Raban, Avner; Holum, Kenneth G. (1996). Caesarea Maritima: a retrospective after two millennia. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10378-8.

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- Vailhé, S. (1913). "Caesarea Palaestinae". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Macalister, R. A. Stewart (1911). "Caesarea Palaestina". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). p. 943.

- "Cæsarea Palestinæ". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

External links

[edit] Media related to Caesarea Maritima at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Caesarea Maritima at Wikimedia Commons- Jewish Encyclopedia: Cæsarea by the Sea

- PBS Frontline – Caesarea

- Archaeology of Caesarea

- Photo gallery of Caesarea

- Photo gallery of Caesarea

- Gavriel Solomon, Caesarea National Park: Conservation Maintenance, Israel Antiquities Authority Site - Conservation Department

- Photos of Caesarea at the Manar al-Athar photo archive

- Ancient Roman theatres in Israel

- Archaeological sites in Israel

- Crusader castles

- Disestablishments in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Castles and fortifications of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Castles in Israel

- Establishments in the Herodian kingdom

- Former populated places in West Asia

- Jews and Judaism in the Roman Empire

- Maritime archaeology in Israel

- New Testament cities

- Populated places established in the 1st century BC

- Populated places of the Byzantine Empire

- Protected areas of Haifa District

- Roman aqueducts outside Rome

- Roman towns and cities in Israel

- Talmud places

- 1100s establishments in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Phoenician cities

- World Heritage Tentative List

- Caesarea Maritima

- Destroyed populated places