Alexander (Byzantine emperor)

| Alexander | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |||||

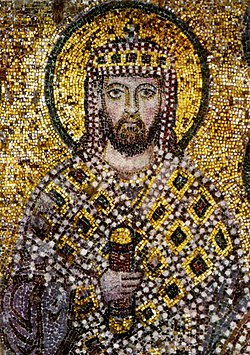

Mosaic of Emperor Alexander in Hagia Sophia. He wears a loros and holds the akakia in his right hand. | |||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Reign | 11 May 912 – 6 June 913 | ||||

| Coronation | c. September 879[a] | ||||

| Predecessor | Leo VI | ||||

| Successor | Constantine VII | ||||

| Born | 23 November 870[4] Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) | ||||

| Died | 6 June 913 (aged 42) | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Macedonian | ||||

| Father | Basil I | ||||

| Mother | Eudokia Ingerina | ||||

Alexander[b] (Greek: Άλέξανδρος, Alexandros, 23 November 870 – 6 June 913) was briefly Byzantine emperor from 912 to 913, and the third emperor of the Macedonian dynasty.

Life

[edit]Born in the purple, Alexander was the third son of Emperor Basil I and Eudokia Ingerina. Unlike his older brother Leo VI the Wise, his paternity was not disputed between Basil I and Michael III because he was born years after the death of Michael.[12] As a child, Alexander was crowned as co-emperor by his father in early 879, following the death of Basil's son Constantine.[13]

Upon the death of his brother Leo on 11 May 912, Alexander succeeded as senior emperor alongside Leo's young son Constantine VII. He was the first Byzantine emperor to use the term "autocrator" (αὐτοκράτωρ πιστὸς εὑσεβὴς βασιλεὺς) on coinage to celebrate the ending of his thirty-three years as co-emperor.[14] Alexander promptly dismissed most of Leo's advisers and appointees, including the admiral Himerios, the patriarch Euthymios, and the empress Zoe Karbonopsina, the mother of Constantine VII, whom he locked up in a nunnery.[14] The patriarchate was again conferred on Nicholas Mystikos, who had been removed from this position due to his opposition to Leo's fourth marriage.

During his short reign, Alexander found himself attacked by the forces of Al-Muqtadir of the Abbasid Caliphate in the east, and provoked a war with Simeon I of Bulgaria by refusing to send the traditional tribute on his accession. Alexander died soon after, allegedly from a stomach disease caused by excessive eating and alcohol.[15]

The sources are uniformly hostile towards Alexander, who is depicted as lazy, lecherous, drunk, and malignant, including the rumor that he planned to castrate the young Constantine VII in order to exclude him from the succession. He did not, but Alexander did leave his successor a hostile regent (Nicholas Mystikos) and the beginning of a long war against Bulgaria. The sources also accused the emperor of idolatry, including making pagan sacrifices to the golden statue of a boar in the Hippodrome, and providing it with new teeth and genitals, in hope of curing his impotence.[16]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ There is some evidence that Alexander was already crowned by August 879, but most sources agree that he was appointed co-emperor following the death of his brother Constantine.[1][2] He was certainly made co-emperor before November 879.[3]

- ^ Alexander is most commonly not assigned a regnal number.[6][7][8] If assigned one, he is rarely regarded as Alexander II, after Severus Alexander (r. 222–235)[9] or even more rarely as Alexander III[10] after both Severus Alexander and Domitius Alexander (r. 308–310). He has also been called Alexander I.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ "Alexandros (#20328)". De Gruyter.

- ^ Tougher 1996, pp. 475–476.

- ^ Mango, Cyril (2018) [1958]. The Homilies of Photius. Dumbarton Oaks studies. Vol. 3. p. 179. ISBN 9781532641381.

- ^ Grierson 1973, p. 475.

- ^ Coinage from 912-913, unlike the coins issued during his co-rules, refers to him as Alexandros Augustos

- ^ Browning 1980, p. 297.

- ^ Haldon 2005, p. 176.

- ^ Lawler 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Granier 2018, p. 224.

- ^ Tougher 1996, p. 209.

- ^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Alexander". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 115.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 233.

- ^ a b Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 261.

- ^ Skylitzes, Ioannes (2010) [1100]. Synopsis of History. Translated by John Wortley. p. 190.

[Alexander] came down to play ball (tzykanion). A pain arose in his entrails which had been overloaded with an excess of food and excessive drinking. He went back up into the palace haemorrhaging from his nose and his genitals; after one day he was dead.

- ^ Karlin-Hayter 1969.

Sources

[edit]- Karlin-Hayter, P. (1969). "The Emperor Alexander's Bad Name". Speculum. 44 (4): 585–596. doi:10.2307/2850385. JSTOR 2850385. S2CID 161599458.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1969). History of the Byzantine State. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-0599-2.

- Granier, Thomas (2018). "Rome and Romanness in Latin southern Italian sources, 8th–10th centuries". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Grifoni, Cinzia (eds.). Transformations of Romanness: Early Medieval Regions and Identities. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059838-4.

- Grierson, Philip (1973). Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection. Vol. 3, Leo III to Nicephorus III, 717–1081. p. 475. ISBN 0-88402-012-6.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), "Alexander", Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, pp. 56–57, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- Browning, Robert (1980). The Byzantine Empire (Revised ed.). The Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0813207544.

- Haldon, John (2005). The Palgrave Atlas of Byzantine History. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230243644.

- Jenkins, Everett (1999). The Muslim Diaspora: A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam. Vol. 1. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786447138.

- Lawler, Jennifer (2015) [2004]. Encyclopedia of the Byzantine Empire. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6616-0.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes; Ludwig, Claudia; Zielke, Beate; Pratsch, Thomas, eds. (2013). Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit (in German). De Gruyter.

- John Julius Norwich (1993). Byzantium, The Apogee. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140114483.

- Tougher, Shaun (1996). The Reign of Leo VI (886-912): Politics and People. Leiden; New York; Köln: Brill. ISBN 9004108114.