Chen Duxiu

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (May 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

Chen Duxiu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

陳獨秀 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

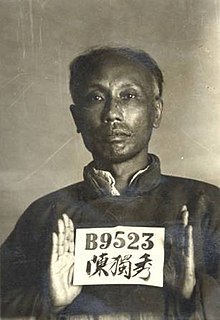

Chen, c. early 1940s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 July 1921 – 1 July 1928 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Xiang Zhongfa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 July 1921 – 7 August 1927 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Position abolished | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of the Central Bureau of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 July 1921 – 7 August 1927 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Position abolished | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 8 October 1879 Anqing, Anhui, Qing dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 27 May 1942 (aged 62) Jiangjin, Chongqing, Sichuan, Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party (1921–1929) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Gao Xiaolan (高晓岚) Gao Junman (高君曼) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Qiushi Academy (currently Zhejiang University) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陳獨秀 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 陈独秀 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 仲甫 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pen name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 三愛 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 三爱 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Three Loves | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chen Duxiu[a] (8 October 1879 – 27 May 1942) was a Chinese revolutionary socialist, educator, philosopher and author, who co-founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) with Li Dazhao in 1921. From 1921 to 1927, he served as the Communist Party's first general secretary. Chen was a leading figure in both the Xinhai Revolution that overthrew the Qing dynasty and the May Fourth Movement for scientific and democratic developments in the early Republic of China. After his expulsion from the CCP in 1929, Chen was for a time the leader of China's Trotskyist movement.

Chen's ancestral home was in Anqing, Anhui, where he established the influential vernacular Chinese periodical New Youth. In order to support overthrowing the Qing government, Chen Duxiu had joined Yue Fei Loyalist Society (岳王會; Yuèwáng huì; Yüeh4-wang2 hui4) which emerged from Gelaohui in Anhui and Hunan province.[1]

Biography

[edit]Life in the Qing dynasty

[edit]Chen Duxiu was born on 8 October 1879 in the city of Anqing, in the Anhui province of the Qing Empire. He was the youngest of four children born to a wealthy family of officials. In his youth, he was described as volatile, emotional, intuitive, non-intellectual, and a defender of the underdog.[2] His father died when Chen was two years old, and he was raised primarily by his grandfather; and, later, by his older brother.

Chen was given a traditional Confucian education by his grandfather, several private tutors, and his elder brother.[3] A thorough knowledge of Confucian literary and philosophical works was the pre-requisites for civil service in Imperial China. Chen was an exceptional student, but his poor experiences taking the Confucian civil service exams resulted in a lifelong tendency to advocate unconventional beliefs and to criticize traditional ideas.

Chen passed the county- and provincial-level imperial examinations in 1896 and 1897 respectively.[3] In a sardonic memoir, he recalled the filthy conditions, the dishonesty, and the incompetence during the exams.[2] In 1898, he enrolled at Qiushi Academy (now Zhejiang University) in Hangzhou after passing the entrance exam and studied French, English, and naval architecture.[3] In October 1901, Chen went to Imperial Japan, studying Japanese at the Tokyo Higher Normal School before attending the Tokyo Special School (the predecessor of Waseda University). He moved to Nanjing in 1902, after reportedly making speeches attacking the Qing government, and then back to Japan the same year under a government scholarship to study at the Tokyo Shimbu Gakko, a military preparatory academy. He returned to China in March 1902 and, together with Bo Wenwei and others, formed the "Youth Self-Strengthening Society." It was the first time in China that the slogan "Science and Democracy" was proposed. It was in Japan where Chen became influenced by socialism and the growing Chinese dissident movement. While studying in Japan, Chen helped to found two radical political parties, but refused to join Tongmenghui Revolutionary Alliance, which he regarded as narrowly racist.[2] In 1908, he accepted a teaching position at the Army Elementary School in Hangzhou.[3][4][5]

Life in the early republic

[edit]From the late 19th century, the Qing dynasty suffered a series of military defeats against the colonial foreign powers, most recently in the First Sino-Japanese War and the war against the Alliance of Eight Nations, which invaded China in response to the 1901 Boxer Rebellion. Government corruption resulted in economic paralysis and widespread impoverishment. During this time, Chen became increasingly influential within the revolutionary movement against both foreign imperialism and the Qing.

Influenced by his time in Japan, Chen founded the Anhui Patriotic Association in 1903 and the Yue Fei Loyalist Society in 1905.[6] By 1905, the Yue Fei included anti-Qing gentry like Sun Yujing and Bo Wenwei. Chen was an outspoken writer and political leader by the time of the Wuchang Uprising of 1911, which started the Xinhai Revolution and led to the collapse of the Qing dynasty. Yue Fei branches were added in Wuhu and Anqing, with those in Anqing infiltrating and agitating within the Qing military.[1] In 1912, Chen became secretary general to the new military governor of Anhui, while also serving as the dean of a local high school. He used the Yue Fei Loyalist Society to establish an organization of students from Anhui public school, pro-rebel Qing soldiers and secret society members.[1] However, Chen fled to Japan again in 1913 following the short-lived "Second Revolution" against Yuan Shikai, but returned to China soon afterwards.[3] He also created the Anhui Patriotic Society associated with the Anhui public school. These organizations won Chen recognition in Anhui, and contact with nationally prominent revolutionaries.[1]

In the summer of 1915, Chen founded the journal Youth – renamed to New Youth (La Jeunesse) in 1916 – in Shanghai. It quickly became the most popular and widely distributed journal amongst the intelligentsia of the Republic of China. The journal criticized conservative Chinese morality and Confucianism; it supported individualism and a Western moral system valuing human rights, democracy and science, which Chen believed Confucianism opposed. The journal also promoted vernacular writing instead of traditional Confucian writing conventions.[7]

Chen joined the faculty of Peking University in the January 1917 as the university's dean, at the invitation of Cai Yuanpei, who also paid for moving Chen's journal to Beijing.[2] As a professor and dean at Peking University, he wrote "If we wish to construct a new state and organize a new society in order to seek an existence suitable to our modern times, then the fundamental issue is that we must import the foundation of a Western-style society and country, that is to say, the new faith in equality and human rights... Unless [Confucianism] is suppressed, [the new Way] will not prevail; unless [supporters of Confucianism] are stopped, [the new Way] will not be practiced."[8] Chen definition of Western civilization focused on egalitarianism rather than competition. He wrote: "socialism is, therefore, a theory of social revolution succeeding political revolution; its aim is to eliminate all inequality and oppression. We can call it 'contemporary' European civilization, which opposes the (merely) 'modern'."[8] A Marxist study group at the university, led by Li Dazhao, attracted his attention in 1919. Chen published a special edition of New Youth on Marxism with Li as the edition's general editor; the edition provided the most detailed analysis of Marxism then published in China, and the journal's popularity ensured its wide dissemination.[9] Chen was involved with the May Fourth Movement, where his and Hu Shih's ideas were labelled as being anti-government and the core of the "New Culture Movement".[10] In the fall of 1919, conservative opponents at the university forced Chen to resign.[9] Around that time he was jailed for three months by the Peking authorities for distributing "inflammatory" literature that demanded the resignation of pro-Japanese ministers, and government guarantees for the freedoms of speech and assembly. After his release, Chen moved to the French Concession[11] in Shanghai and became more interested in Marxism and the promotion of rapid social change;[12] there he pursued his intellectual and scholarly interests free from official persecution.[citation needed] After reading the Bible in prison, he was said to have been a Nondenominational Christian[13][14] or liberal Protestant before becoming dissatisfied with Christianity.[15] In 1921, he also lived and worked at a Protestant[16] church school.[17]

The newspaper Shen Bao categorized academics into factions (xuepai). It portrayed Chen and Hu as victims of government persecution, and their opponents as allies of the warlords.[10]

Career within the Chinese Communist Party

[edit]Founding the Chinese Communist Party

[edit]

In 1921, Chen, Li and other prominent revolutionaries (including Mao Zedong) founded the CCP. It has been generally asserted that the group had diligently studied Marxist theories, inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917.[3] Chen was elected (in absentia) as the first General Secretary at the first party congress in Shanghai.[18] He remained the undisputed leader of the party until 1927, and was often referred to as "China's Lenin" during this period.[3]

Chen, with Li's assistance, developed a cooperative – and later troublesome – relationship with the Communist International (Comintern). Over the next decade, the Comintern sought to use the CCP as tools of Soviet foreign policy, leading to policy disagreements between CCP leaders and Comintern advisors.[18]

By 1922, the party had only about 200 members, not counting those overseas.[19]

Subsequent efforts to spread communism

[edit]Soon after the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, in 1921, Chen accepted an invitation from Chen Jiongming to serve on the education board in Guangzhou in the aftermath of the June 16 Incident, but this position dissolved when Guangzhou was recaptured by the Kuomintang. At the direction of the Comintern, Chen and the Chinese Communists formed an alliance with Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT or Nationalist Party) in 1922. Although Chen was not convinced of the utility of collaborating with the Kuomintang, he reluctantly carried out the Comintern's orders to do so. Pursuing collaboration with the Kuomintang, he was elected into that party's Central Committee in January 1924.[3]

In 1927, after the Shanghai massacre, he and other high-ranking Communists, including Mao Zedong and Mikhail Borodin, collaborated closely with Wang Jingwei's Nationalist government in Wuhan, convincing Wang's regime to adopt various proto-Communist policies. The Wuhan government's subsequent land reform policies were considered provocative enough to influence various KMT-aligned generals to attack Wang's regime, suppressing it.[20] Chen was forced to resign as General Secretary in 1927, due to his public dissatisfaction with the Comintern order to disarm during the April 12 Incident, which had led to the deaths of thousands of Communists – now known as the Shanghai massacre of 1927, and because of his disagreement with the Comintern's new focus on peasant rebellions.[citation needed]

Conflict with Mao

[edit]Chen came into conflict with Mao Zedong in 1925 over Mao's essay "An Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society". Mao opposed Chen's analyses of China. While Chen believed that the focus of revolutionary struggle in China should primarily concern the workers, Mao had started to theorize about the primacy of the peasants. According to Han Suyin in Mortal Flower, Chen "opposed the opinions expressed [in Mao's analysis], denied that a radical land policy and the vigorous organization of the rural areas under the Communist party was necessary, and refused the publication of the essay in the central executive organs of publicity."

Although he recognized the value of Mao's interpretation of Marxism in inciting the Chinese peasants and labourers to revolution, Chen opposed Mao's rejection of the strong role of the bourgeoisie that Chen had hoped to achieve. During the last years of his life, Chen denounced Stalin's dictatorship, and held that various democratic institutions, including independent judiciaries, opposition parties, a free press, and free elections, were important and valuable. Because of Chen's opposition to Mao's interpretation of Communism, Mao believed that Chen was incapable of providing a robust historical materialist analysis of China. This dispute would eventually lead to the end of Chen and Mao's friendship and political association.[3]

Expelled by the party

[edit]After the collaboration between the Communist Party and the KMT fell apart in 1927, the Comintern blamed Chen, and systematically removed him from all positions of leadership. In November 1929, he was expelled. Afterwards, Chen became associated with the International Left Opposition of Leon Trotsky. Like Chen, Trotsky opposed many of the policies of the Comintern, and publicly criticized the Comintern's effort to collaborate with the Nationalists. Chen eventually became the voice of the Trotskyists in China, attempting to regain support and influence within the party, but failed.[3] Chen continued to oppose measures like "New Democracy" and the "Block of Four Classes" advocated by Mao Zedong.

After the communist movement in the late 1920s, Chen Duxiu and Leon Trotsky started to have a complex relationship that was not known in the west. Their relationship reveals the developments of Trotskyism in China and deepen the understanding of the relationship between the Communists of China and Soviet Union. Due to lack of related resources, the public did not have a full understanding of the relationship between Chen Duxiu and Leon Trotsky. Nowadays, this situation has already improved a lot by following reasons. Firstly, more printed Chinese materials about Chen Duxiu are available. Secondly, in 1980, the "Exile papers of Leon Trotsky" which includes letters, personal notes, manuscripts, and many unpublished resource were accessible.[21]

Last years

[edit]In 1932, Chen was arrested by the government of the Shanghai International Settlement, where he had been living since 1927, and extradited to Nanjing. In 1933, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison by the Nationalist government, but was released on parole in 1937 after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War.[3]

Chen was one of the few early leaders of the Communist party to survive the turmoil of the 1930s, but he was never able to regain any influence within the party he had founded. For the last decade of his life, he faded into obscurity. At the time that he was released, both the supporters of Chen and the pro-Comintern leaders who opposed him had either been killed or had fallen out of favor with the Communist membership. The Chinese Communist Party managed to survive the purges only by fleeing to the northern frontier in the Long March of 1934–1935, during which Mao Zedong emerged as leader. If only for sheer survival, the Communists had to flee the cities where China's fledgling industrial working class was concentrated, seek refuge in remote rural areas, and there mobilize the support of peasants; this was naturally taken as a vindication of Mao's position in his debate with Chen. Mao and this new generation of Communists would lead the party in China for the next fifty years.

On 23 August, Chen was released from prison and refused multiple offers of positions from the Kuomintang. He said that despite the importance of the war effort, "Chiang Kai-shek killed many of my comrades. He also killed my two sons. He and I are absolutely irreconcilable." In August 1937, Chen met with the heads of the Chinese Communist Party Office in Nanjing. This led to a concerted attempt by Luo Han and Ye Jianying to allow Chen to return to the Party. In September Mao responded saying that Chen could rejoin the party if he agreed to publicly renounce Trotskyism and express support for the United Front against Japan. Chen responded by letter to the Central Committee of the CCP that he agreed with its line of resistance but would not renounce Trotskyism. This was the end of the last serious attempt to rejoin the CCP.[22]

Chen then travelled from place to place until the summer of 1938, when he arrived at the wartime capital of Chongqing and took a position teaching at a junior high school. In poor health and with few remaining friends, Chen Duxiu later retired to Jiangjin, a small town west of Chongqing, where he died in 1942 at the age of 62.[3] Today, he is buried at his birthplace of Anqing.

Legacy

[edit]After the founding of the PRC in 1949, Chen's example was used to warn Communist Party members not to deviate from party orthodoxy. In the Hundred Flowers Campaign, the example of Chen in collaborating with Wang Jingwei's Wuhan government, leading to the ostracism of his peers and the failure of Communist policies at the time, was used by Peng Zhen as a warning never to "forgive" anti-Maoists.[23] After Mao died in 1976, Hua Guofeng gave a speech praising Mao's suppression of "Right and 'Left' Opportunist lines of the Party" as one of the late chairman's greatest achievements: Chen was the first person to be named as being correctly suppressed; Deng Xiaoping was the last.[24]

Hu Qiaomu's 1951 Thirty Years of the Chinese Communist Party, which was deemed by the Party as its authoritative history,[25] denounced Chen as:

- a bourgeois democracy opportunist;

- Right opportunist;

- Right capitulationist;

- factionalist;

- anti-Soviet;

- anti-Comintern;

- anti-Party;

- counter-revolutionary;

- traitor to China; and

- a turncoat.

In 1956, Mao Zedong said that Chen represented the gravest of all of the deviations to the Right in the party's history up to that time.[26]

Chen's contributions to the Party have subsequently been reassessed, however. Hong Kong historian Tang Baolin called Hu's verdict on Chen the greatest miscarriage of justice in the Party's history[27] and although his reassessment of Chen has not been officially endorsed by the Party, it was published in 2009 by the Chinese Literature and History Press which is run by the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.[28]

Literature

[edit]Writing style

[edit]Chen felt that his articles should reflect the needs of society. He believed that the progress of society could not be achieved without those who accurately report social weaknesses and sicknesses.

Chen's articles were always expressive. He criticized the traditional Chinese officials as corrupt and guilty of other wrongdoings. He was under constant attack from conservatives in China, and had to flee to Japan four times. In China, he spent much of his life in the French Concession and the Shanghai International Settlement in order to pursue his writing and scholarly activities free from official harassment.

Chen's articles strove to attract publicity, and often arouse discussion by using hyperbole. He lashed out against the backwardness and corruption in China. In New Youth, he wrote various articles using pseudonyms to form "discussions", in order to arouse public interest.[citation needed]

Chen's publications emphasized the responses from their audience. In New Youth there were forums and citizens' columns. On average, there were 6 letters from the public in each issue. Whether in praise or strong opposition, Chen encouraged all to write. He also thought that teamwork was very important in journalism, and consequently asked for help from many talented authors and journalists, including Hu Shih and Lu Xun.

Journalistic works

[edit]Anhui Suhua Bao

[edit]On 31 March 1904, Chen founded Anhui Suhua Bao, a newspaper that he established with Fang Zhiwu and Wu Shou in Tokyo to promote revolutionary ideas using vernacular Chinese, which was simple to understand and easy for the general public to read. While Chen was the chief secretary of the newspaper, its circulation increased from only a thousand copies to more than three times that figure in less than half a year, becoming one of the most popular vernacular Chinese newspapers in print at that time. During 1904 and 1905, a total of twenty-three issues were published. Each issue had 40 pages – about 15,000 words. However, due to political pressures, the paper was barred from publishing in 1905.

Chen had three main objectives in publishing Anhui Suhua Bao: to let his countrymen in Anhui keep abreast of the politics of the Qing dynasty; to spread knowledge to the paper's readers through vernacular Chinese; and, to promote revolutionary ideas to the public. Chen believed that most Chinese believed that the importance of the family was greater than that of the state, and that this limited their interest in political events. He also found Chinese people in general to be excessively superstitious. Chen urged Chinese people to participate in politics through the publication of Anhui Suhua Bao. After its sixteenth issue, the newspaper added an extra 16 columns; the most popular were on military events, Chinese philosophy, hygiene, and astronomy. Almost all of these additional topics were written by Chen. His pen-name was San'ai (三爱/三愛). At least 50 articles were published under this name.

Tokyo Jiayin Magazine

[edit]In early 1914, Chen went to Japan, where he worked as an editor and writer in the Tokyo Jiayin Magazine, which was published by Zhang Shizhao. Chen once wrote an article entitled "Self Consciousness on Patriotism" (爱国心与自觉/愛國心與自覺) which conveyed a strong sense of patriotism and encouraged people to fight for their freedom. It promoted the idea that those who love their country should spare no pains to protect it, and should fight for the rights of its citizens. This group of people should work together towards the same goal harmoniously. The article was threatening to Yuan Shikai's government, as it tried to arouse the self-consciousness of the Chinese people. This preliminary magazine was released for 10 issues in total, before it was prevented from publishing. The magazine was resumed in 1925 in Beijing with the new name Tokyo Jiayin Weekly.

New Youth magazine

[edit]In 1915, Chen started an influential monthly periodical in the French Concession of Shanghai, The Youth Magazine (青年杂志/青年雜誌), which was later renamed New Youth (新青年, literally New Youth).[1] It became one of the most influential magazines among the students who participated in the May Fourth Movement. Chen was the chief editor of this periodical. It was published by Qunyi Shushe, and ended publication in 1926. The magazine mainly advocated the use of vernacular language, socialism, and Marxism, and was strongly against feudalism.

In 1917, Chen became a lecturer of Chinese Literature, and a Dean of Peking University. Having the approval from the Cai Yuanpei, the Chancellor of the Peking University, Chen collected the writings of the students which he appreciated most, which especially included Li Dazhao, Hu Shih, Lu Xun and Qian Yuan. In order to expand the editorial department, New Youth was moved to Beijing at this time, and in February 1917, Chen used New Youth to promote science, democracy and modern literature, and to discourage the study of paleography and classical Chinese literature. The magazine began to advocate the use of the scientific method and Logical arguments towards the achievement of political, economic, social, ethical, and democratic goals.

New Youth focused on different concerns during various phases of its development. From 1915 to 1918 it opposed Chinese conservatism (especially conservatism associated with Confucianism) and promoted the development of democracy. During this phase, it became influential among the New Culture Movement. From 1919 to 1921, until the formation of the Chinese Communist Party, it focused on promoting socialism, and Marxism. From 1921 to 1926, it published and disseminated the prevailing views of the members of the Communist Party.

Minor publications

[edit]The Shanghai local government banned the sale of a publication called "Guomin Ribao" (国民日报/國民日報) on 1 December 1903. After this, Chen twice planned to found a paper called "Aiguo Xinbao" but failed because of pressure from different groups. Chen continued to express his discontent towards the government in his later publications. When Anhui Suhua Bao was published on 31 March 1904, Chen was responsible for all editing and distribution.

On 27 November 1918, Chen started another magazine, the Weekly Review (每周评论/每週評論) with Li Dazhao in order to criticize the politics of his time in a more direct way and to promote democracy, science, and modern literature. Chen also edited Tokyo Jiayin Magazine (甲寅杂志/甲寅雜誌) and Science Magazine (科学杂志/科學雜誌). Later, he became the Editor-in-Chief of the newspapers Minli Bao (民立报/民立報) and Shenzhou Daily (神州日报/神州日報).

From 1908 to 1910, two students at Peking University, Deng Zhongxia and Xu Deheng, founded the Guomin magazine and invited Li Dazhao to be a consultant for the magazine. From 1912 to 1913, Chen, with the assistance of Luo Jialun and Fu Sinian, published a paper named Xinchao She.

Chen's contribution to Chinese journalism

[edit]Chen set a precedent for future writers via the intentionally controversial nature of his publications. He insisted on telling the truth to the Chinese people and strengthening the Chinese media for later generations. By publishing newspapers and magazines concerning political issues, Chen provided a channel for the general public to express their ideas or discontent towards the existing government. Chen believed that the purpose of mass media was to reveal the truth. At a young age, Chen had already established his first periodical, Guomin Ribao, in which he criticized many social and political problems evident in the late Qing dynasty. With a view to the things mentioned above, his contribution was said to be influential to journalism as a whole. Chen's writing brought the standards of Chinese journalism closer to those of other, more liberal societies of his time.

Poetry

[edit]In 1918, New Youth published contemporary poetry by Hu Shih and Liu Bannong, written in vernacular Chinese, becoming one of the first publications in China to encourage poetry in vernacular Chinese. Eventually, every article in New Youth was written in vernacular Chinese. New Youth was one of the first publications in China to adopt and use punctuations marks, and popularized their use through its popularity and wide readership.

Final letters and articles

[edit]Gregor Benton compiled and translated into English the last of Chen Duxiu's writings, publishing them under the title "Chen Duxiu's last articles and letters, 1937–1942".[29]

Intellectual contributions and disputes

[edit]Crisis with Cai Yuanpei

[edit]In the second edition of New Youth, Chen prepared to publish Cai Yuanpei's speech, the "Speech on Freedom of Religion" (蔡元培先生在信教自由会之演说/蔡元培先生在信教自由會之演說), along with an editorial interpreting its meaning and significance. Before its appearance in New Youth, Cai criticized Chen for misinterpreting this speech. Chen later admitted that "the publication of my speech in New Youth included a number of mistakes." Fortunately, Cai did not become angry with Chen and the publication was then amended before publishing.

Crisis with Hu Shih

[edit]This crisis was about the political stand of New Youth. Hu Shih insisted that New Youth should be politically neutral and the publication should be concerned with Chinese philosophy. Chen attacked his rationale by publishing "Talking Politics" (谈政治/談政治) in the 8th edition. Because Chen was invited by Chen Jiongming to be the Education officer in Guangzhou in mid-December 1920, he decided to assign the publication to Mao Dun, who belonged to the Shanghai Communist Party.

Hu Shih was dissatisfied with this responsibility and their friendship and professional relationship ended. Later, Chen wrote to Hu Shih about his dissatisfaction with Hu's intimacy with many conservative faculty members of Peking University. Especially troubling to Chen was Hu's relationship with Liang Qichao, a supporter of the Duan Qirui government and their anti-new wave ideology, which made Chen greatly dissatisfied.

Crisis with Liang Shuming

[edit]Chen Duxiu viewed human history as a whole thing, as a single entity. A monistic evolutionary historical model was suggested by Chen Duxiu's argument. On the other hand, Liang Shuming clearly divided cultures into three types: European culture, Chinese culture and Indian culture.[30] European culture is characterized as the “primary, forward-seeking orientation”; Chinese culture is the “secondary, harmony and middle-ground-seeking orientation”; and Indian culture, the “tertiary, self-reflective and backward-looking orientation.”[30] Chen Duxiu said "In many people’s estimation, the differences among Chinese, Indian, and European culture are almost entirely differences in ethnicity, and thus are not limited to those of culture.” [30] This argument is clearly about criticizing Liang's Eastern and Western Cultures and Philosophies.

Views on Confucianism and traditional values

[edit]Chen suggested six guiding principles in New Youth with an article called "Warning the youth" (敬告青年). This article was aimed at removing the old beliefs of Confucianism. "Warning the Youth" promoted six values:

- Independence instead of servility;

- Progressivism instead of conservatism;

- Aggression instead of passivity;

- Cosmopolitanism instead of isolationism;

- Utilitarian beliefs instead of impractical traditions;

- Scientific knowledge instead of visionary insight.

New Youth was one of the most influential magazines in early modern Chinese history. Chen introduced many new ideas into popular Chinese culture, including individualism, democracy, humanism, and the use of the scientific method, and he advocated the abandonment of Confucianism for the adoption Communism.

Seen in this light, New Youth found itself in a position to provide an alternative intellectual influence for many young people. Under the banners of democracy and science, traditional Confucian ethics became the target of attack from New Youth. In its first issue, Chen called for young generation to struggle against Confucianism by "theories of literary revolution" (文学革命论; 文學革命論).

To Chen, Confucianism was to be rooted out because:

- It advocated superfluous ceremonies and preached the morality of meek compliance, making the Chinese people weak and passive, unfit to struggle and compete in the modern world.

- It promoted family values and rejected the idea that the individual was the basic unit of society.

- It upheld the inequality of the status of individuals.

- It stressed filial piety, which made men subservient and dependent.

- It preached orthodoxy of thought, disregarding freedom of thinking and expression.

Chen called for the destruction of tradition, and his attacks on traditionalism gave new options to the youth of his time. New Youth was a major influence within the May Fourth Movement.

Views on democracy and the Soviet Union

[edit]In My Fundamental Opinions written in November 1940, Chen Duxiu wrote about his views concerning democracy, socialism and the Soviet Union. He reflected on the Communist movement and provided his thoughts on related issues, fundamentally rejecting some of the core tenets of Communism.

- We should understand the lessons of Soviet Union in the past two decades without prejudices, scientifically rather than religiously reevaluate Bolshevik theory and its leadership. We can not attribute all the crimes to Stalin, such as the problems about democratic institutions under the dictatorship of proletariat.

- Democracy of the proletariat is not a meaningless noun. It shares common content with bourgeoise democracy like the freedom of assembly, association, speech, publication and strike. What is especially important is the freedom of opposition parties. Without those things, parliament would also become as worthless as a soviet.

- Democracy in politics and socialism in economy is mutually supportive instead of opposing things. Democracy is not inseparable from capitalism and bourgeoisie. If the political parties of the proletariat also oppose democracy because of their opposition against capitalism, even if so called 'the revolution of proletariat' really appears, without democracy's disinfection of bureaucracy, only bureaucratic regimes like Stalin's would appear in the world, brutal, corrupted, hypocritical, deceptive, rotten. Socialism is absolutely impossible. There is absolutely no such thing like 'the dictatorship of proletariat'. It is just the dictatorship of the party, finally the dictatorship of the leader. Any kind of dictatorship is bound with brutality, obscurantism, deception and corruption and rotten bureaucratic politics.[31]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Chinese: 陳獨秀; pinyin: Chén Dúxiù; Wade–Giles: Ch'en Tu-hsiu

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Chao, Anne S. (2017). "The Local in the Global: The Strength of Anhui Ties in Chen Duxiu's Early Social Networks, 1901–1925". Twentieth-Century China. 42 (2): 113–137. doi:10.1353/tcc.2017.0015. ISSN 1940-5065. S2CID 149130353.

- ^ a b c d Spence 1999, p. 303.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Chow 2009.

- ^ Chao 2009.

- ^ "留日的中国共产党的创始人陈独秀、李大钊及四位"一大"代表". m.sohu.com. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "네이버 학술정보".

- ^ Spence 1999, pp. 303–304.

- ^ a b Paramore, Kiri (6 July 2018). "Liberalism, Cultural Particularism, and the Rule of Law in Modern East Asia: The Anti-Confucian Essentialisms of Chen Duxiu and Fukuzawa Yukichi Compared". Modern Intellectual History. 17 (2): 527–542. doi:10.1017/s1479244318000240. ISSN 1479-2443.

- ^ a b Spence 1999, p. 296.

- ^ a b Forster, Elisabeth (2018). 1919 – The Year That Changed China. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110560718. ISBN 978-3-11-056071-8.

- ^ Spence 1999, p. 309.

- ^ Spence 1999, p. 304.

- ^ 沈寂 (2007). 陈独秀传论 (in Simplified Chinese). 安徽大学出版社. ISBN 978-7-81110-298-7.

- ^ 五四運動與中國宗教的調適與發展. 中央研究院近代史研究所. December 2020. ISBN 978-9865432522.

- ^ Christian Women and Modern China: Recovering a Women's History of Chinese Protestantism. Rowman & Littlefield. 2021. ISBN 978-1793631572.

- ^ "Protestantism". Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ 五四运动在武汉史料选辑. 湖北人民出版社. 1981.

- ^ a b Columbia 2001.

- ^ Spence 1999, p. 312.

- ^ Spence 1999, pp. 338–339.

- ^ Kuhfus, Peter (June 1985). "Chen Duxiu and Leon Trotsky: New Light on their Relationship". The China Quarterly. 102: 253–276. doi:10.1017/S0305741000029933. ISSN 0305-7410. S2CID 154305254.

- ^ Benton 2017, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Spence 1999, p. 543.

- ^ Spence 1999, p. 615.

- ^ Weigelin-Schwiedrzik 1993, p. 154.

- ^ U.S. Imperialism is a paper tiger Interview with Chairman Mao Marxists Internet Archive 14 July 1956

- ^ "Chen Biography Author: Mao Zedong's 'Nobility'" Shenzhen Daily 15 November 2013

- ^ The greatest injustice in the history of the CPC: Chen's nine charges all groundless Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine in Declassified documents in the broad historical picture Ye Kuangzheng ed. Chinese Literature and History Press February 2009

- ^ Benton 1998.

- ^ a b c Mizoguchi, Yūzō (2016). "Another May Fourth". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 17 (4): 606–631. doi:10.1080/14649373.2016.1244032. ISSN 1464-9373. S2CID 214652297.

- ^ 陳獨秀. (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

Sources

[edit]- "Comintern". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2001. Archived from the original on 12 October 2004.

- Benton, Gregor, ed. (1998). Chen Duxiu's last articles and letters, 1937–1942. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2112-2.

- Benton, Gregor (2017). Prophets unarmed: Chinese Trotskyists in revolution, war, jail, and the return from limbo. Haymarket Books.

- Chao, Anne Shen (2009). Chen Duxiu's Early Years: The Importance of Personal Connections in the Social and Intellectual Transformation of China 1895–1920 (Thesis). Houston, Texas: Rice University.

- Chow, Tse-tsung (2009). "Chen Duxiu". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Search for Modern China. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-97351-4.

- Weigelin-Schwiedrzik, Susanne (1993). "Party Historiography". In Unger, Jonathan (ed.). Using the Past to Serve the Present: historiography and politics in contemporary China. New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Further reading

[edit]- Chen, Duxiu. Chen Duxiu's Last Articles and Letters: 1937–1942 (University of Hawaii Press, 1998).

- Lee Feigon (1983). Chen Duxiu, Founder of the Chinese Communist Party. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-05393-6.

- Kagan, R. C. (1972). "Ch'en Tu-Hsiu's Unfinished Autobiography". The China Quarterly. 50: 295–314. doi:10.1017/S0305741000050323. S2CID 155048443.

- Kuo, Thomas. Ch`en Tu-Hsiu (1879–1942) and the Chinese Communist movement (Seton Hall University Press. 1975).

External links

[edit]- Broué, Pierre. "Chen Duxiu and the Fourth International, 1937–1942", 1990 article at Marxists.org.

- Zheng Chaolin, "Trotskyism in China", article on Revolutionary History Website.]

- Articles on the Anhui Suhua Bao 《安徽俗话报/安徽俗話報》 (in Chinese)

- Chenduxiu page (in Chinese)

- 1879 births

- 1942 deaths

- Burials in Chongqing

- Chinese Communist Party politicians from Anhui

- Chinese expatriates in Japan

- Chinese magazine founders

- Chinese revolutionaries

- Chinese Trotskyists

- Delegates to the 2nd National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

- Delegates to the 3rd National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

- Delegates to the 4th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

- Delegates to the 5th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

- Educators from Anhui

- Members of the 2nd Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Communist Party

- Members of the 4th Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Communist Party

- General secretaries and Chairmen of the Chinese Communist Party

- Academic staff of Peking University

- People from Huaining County

- Philosophers from Anhui

- Political party founders

- Politicians from Anqing

- 20th-century Chinese philosophers

- Republic of China politicians from Anhui

- Zhejiang University alumni

- Academic staff of Zhejiang University

- Chinese language reform