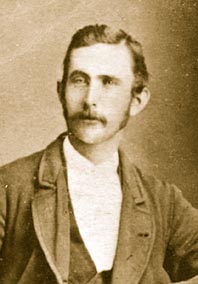

Joe Byrne

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

Joe Byrne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Joseph Byrne 21 November 1856 Beechworth, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 28 June 1880 (aged 23) Glenrowan, Victoria, Australia |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound to the femoral artery |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | Bushranger |

Joseph Byrne (21 November 1856 – 28 June 1880)[1] was an Australian bushranger, outlaw and member of the Kelly gang, referred to as leader Ned Kelly's second in command.

Byrne was born in country Victoria with an Irish Catholic background. He was named after his paternal grandfather, an Irish rebel who was transported as a convict to Australia. Growing up near Chinese mining camps, Byrne became fluent in Cantonese and addicted to opium, and in later years was even mistakenly assumed to be part-Chinese. Through his childhood friend Aaron Sherritt, Byrne became an associate of the Greta Mob, a larrikin gang that counted brothers Ned and Dan Kelly among its members.

Byrne, the Kellys and Steve Hart were outlawed in 1878 for the murder of three policemen at Stringybark Creek. As a result of this and raids on Euroa and Jerilderie, bushranging's largest ever reward was placed on their heads. In 1880, Byrne, believing Sherritt had turned police informer, murdered him as part of a plot to derail a police train and raid Benalla, but the gang was cornered by the police at a hotel in Glenrowan. Despite wearing bulletproof armour in the ensuing shootout, Byrne was fatally shot while making a toast in the hotel bar, his final words being, "Many more years in the bush for the Kelly gang!"

Byrne was known for his literary talents, writing out the Jerilderie Letter and other documents on behalf of Ned, and composing bush ballads about the gang. He also had a reputation as a womaniser, and on screen has been portrayed by the likes of Orlando Bloom (Ned Kelly, 2003).

Early years and family

[edit]Byrne was born in 1856 in Woolshed, on the Reedy Creek flat near Beechworth, Victoria, to Irish Catholic parents Patrick Byrne and Margaret (née White). Byrne was named after his paternal grandfather, Irish Whiteboy (agrarian rebel) and convict Joseph Byrne, who was transported to the penal colony of New South Wales in 1833 for "unlawful oaths". Patrick, born in 1831, followed his father to Australia in 1849. Margaret was born at Scariff, County Clare, Ireland. She was one of the "Irish Famine Girls" given free passage to Australia during the Great Famine.[citation needed] Margaret was an indentured servant for Nathaniel Stephen Powell, an Irish-born grazier and the local magistrate for Bungendore, near modern-day Canberra.[citation needed]

Growing up in Woolshed, Byrne received his education at the local Catholic school from 1862. He was considered one of the better students there and developed a reputation as a "flash writer". He also built a strong friendship with fellow student Aaron Sherritt. In 1869, Byrne's father died from heart disease, and Byrne, now the eldest male in the household, left school that year to assume the duties of his deceased father.[citation needed]

Byrne grew up near and frequented Chinese mining camps. As a result, he became fluent in Cantonese and acquired an addiction to opium.

Byrne and Sheritt found themselves in trouble with the law. Byrne made his first appearance in court in 1871 on the charge of illegally using a horse, and had to pay a fine of 20 shillings to avoid going to jail. Byrne and Sherritt were later convicted of stealing a bullock and served six months in HM Prison Beechworth. During this imprisonment, Byrne and Sherritt met Jim Kelly, the brother of Ned Kelly and Dan Kelly. Byrne met Ned in 1876 and the pair soon became firm friends.[citation needed]

Bushranging

[edit]Dan Kelly had discovered an abandoned gold diggings at Bullock Creek, which was worked by the Kelly brothers, Byrne, Sherritt, and Steve Hart during the next couple of years. Byrne was likely present at the Kelly homestead on 15 April 1878 when Constable Fitzpatrick claimed that Ned Kelly shot him and Ellen Kelly, Ned's mother, hit him over the head with a shovel. Afterwards, Ned and Dan Kelly fled to Bullock Creek with a 100-pound bounty on their heads and Ellen Kelly was sentenced to three years hard labour for assaulting a police officer.

Joe Byrne was present at Stringybark Creek with the Kelly brothers and Steve Hart on 26 October 1878 when they surprised a patrol of four police officers on their trail, with three of them shot dead. The gang were declared as outlaws for this incident on 15 November 1878 and a price of £2000 (equivalent to approximately A$754,000 in 2008) was placed on their heads.

The Kelly Gang started developing a strategy with Byrne acting as Kelly's lieutenant, always being consulted about strategy. The Kelly Gang robbed the Euroa branch of the National Bank of Australia stealing over £2,000 which was the largest heist to that point. Joe Byrne drafted the Euroa letter (now known as the Cameron letter)[2] in red ink sent by Ned Kelly to Donald Cameron, a local MLC. claiming that justice had not been done in the case of his mother and himself. It concluded "For I need no lead or powder to revenge my cause, And if words be louder I will oppose your laws."

My name it is Ned Kelly, I'm known adversely well,

My ranks are free, my word is low, wherever I do dwell.

My friends are all united, my mates are lying near,

We sleep beneath shady trees, no danger do we fear.

Lines from one of Byrne's Kelly gang ballads.[3]

The police locked up over 20 alleged supporters of the Kelly gang between 3 January 1879 and 22 April 1879 under the Felons Apprehension Act 1878. This cemented public support for the gang especially in northeast Victoria. Joe Byrne was able to use this support to advantage by penning a number of bush ballads about the exploits of Kelly and his gang.

Joe Byrne frequently visited his mother at her house in Beechworth and was also seen carousing in bars in the town, despite having a price on his head. This was due to a combination of his skill and daring, the incompetence of the police and the support of local residents for the Kelly Gang. There was a Royal Commission into the Victorian Police in 1881 after the capture of the Kelly Gang because of the deficiencies exposed by the Gang.

Kelly and Byrne started planning their next raid at Jerilderie. On 10 February 1879, dressed as police officers, the gang raided the Bank of NSW branch at Jerilderie taking another £2,000. Prior to the raid, Byrne composed the Jerilderie Letter which supported the creation of a Republic of North-eastern Victoria. The proceeds of both the Euroa and Jerilderie robberies were distributed amongst the gang's family, friends and supporters. The Kelly gang shouted the bar at Jerilderie which further enhanced their reputation.

After the Jerilderie raid, the gang laid low for 16 months evading capture. This aided to their reputation and greatly embarrassed the government of Victoria and the police. The Victorian Government eventually increased the reward for capture of a member of the Kelly Gang to £8,000 (equivalent to two million Australian dollars in 2005).

Murder of Sherritt, Glenrowan siege and death

[edit]

Short of funds, the gang made plans to raid Benalla in 1880. During this time, they became increasingly concerned that Aaron Sherritt's allegiance had swayed to the police. Byrne wrote letters to Sherritt, inviting him to join the gang, but grew increasingly wary of his former friend, and murdered him at his hut in the Woolshed Valley on 26 June 1880. A four-man police watch party was then occupying the hut, and hid in one of the rooms. Byrne shoot into the room and threatened to burn the hut down before riding off with Dan Kelly to meet the other gang members at Glenrowan.

That night, the gang took over Glenrowan, first tearing up the railway line in anticipation of a special trainload of police being sent to capture them after news of Sherritt's murder spread. The outlaws held over 60 people hostage in the town. Thomas Curnow, the schoolmaster of the local school who had won Kelly's trust, escaped and warned the train crew who in turn told the police. This enabled 34 police to surround the Glenrowan Hotel and engage in a gunfight with the gang. In the ensuing blaze of light and smoke, the hotel was riddled with bullets, and several hostages were killed or wounded. Byrne received a gunshot wound to the calf.

At around 5:30 a.m., Byrne entered the hotel bar and, after pouring himself a whiskey, made the toast, "Many more years in the bush for the Kelly Gang!" Moments later, a stray bullet entered a gap in his armour, severing his femoral artery. Byrne slumped on top of hostages crouching in fear on the floor, and bled out within minutes.

After Ned Kelly's last stand and capture, the police set fire to the Glenrowan Inn and retrieved Byrne's body before the hotel was consumed by flames. In Byrne's coat pockets were found a prayer book, cartridges and a brown paper bag containing poison. Later that day, his body and the seriously wounded Ned Kelly were conveyed on the same train to Benalla, where they were kept in neighbouring cells in the lockup. The night of their arrival, artist Julian Ashton sketched Byrne's body by candlelight; in later years Ashton called it "the most miserable assignment I have ever had". The next day Byrne's body was strung up "like a puppet" on the door of the lockup and photographed by the press. Max Kreitmayer, owner of Melbourne's Waxworks Museum, made a death mask and other casts of Byrne and, within days, a wax figure of the outlaw was put on exhibition inside the museum's Chamber of Horrors, attracting large crowds. The wax figure had on Byrne's boots from the siege, which were still stained with his blood and initially displayed in the windows of the museum on Bourke Street.[5]

His family did not claim the body, and the police refused to hand it over to sympathisers, fearing a funeral would become a rallying point for the simmering rebellion. He was buried on the same day as Aaron Sherritt. Dan Kelly and Steve Hart also died on the day of the siege by shooting themselves, although there is no concrete evidence of a suicide by Dan Kelly and Steve Hart[6] while Ned Kelly was captured and tried in Melbourne. Ned Kelly was hanged at Old Melbourne Gaol on 11 November 1880.

Cultural references

[edit]In Douglas Stewart's 1942 verse drama Ned Kelly, Byrne is depicted as a poet-philosopher whose function is to articulate what Ned Kelly, a man of action and lawlessness, stands for.

A number of film actors have portrayed Byrne, including Mark McManus in Ned Kelly (1970) and Orlando Bloom in Ned Kelly (2003).

References

[edit]- ^ "Byrne, Joseph (Joe) (1856–1880)". Obituaries Australia. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Kelly, Ned (14 December 1878), The Cameron Letter

- ^ Jones, Ian (1992). The Friendship that Destroyed Ned Kelly: Joe Byrne & Aaron Sherritt. Lothian Pub., ISBN 9780850915181. p. 101

- ^ Powell, Rose (20 March 2015). "First Australian press photo shows body of Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne", The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Gilmour, Joanna (2015). Sideshow Alley: Infamy, the Macabre & the Portrait. National Portrait Gallery. p. 110, 119, 132. ISBN 9780975103067.

- ^ "AN INTERVIEW WITH NED KELLY". The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser. NSW. 1 July 1880. p. 7. Retrieved 3 February 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

External links

[edit]- Joe Byrne: Lieutenant of the Kelly Gang page at the Wayback Machine (archived 9 March 2005)

- Glenrowan 1880 Joe Byrne page

- ABC Online page on Ned Kelly

- La Trobe University media release on speech by Chief Justice of Victoria on the North Eastern Republic of Victoria

- Speech by Victorian Chief Justice John Phillips, Chief Justice of Victoria, at La Trobe University on The North-Eastern Victoria Republic Movement: Myth or Reality[permanent dead link]