Exposition Universelle (1855)

| 1855 Paris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical Expo |

| Name | Exposition Universelle des produits de l'Agriculture, de l'Industrie et des Beaux-Arts de Paris 1855 |

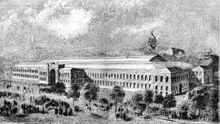

| Building(s) | Palais de l'Industrie |

| Area | 15.2 hectares (38 acres) |

| Visitors | 5,162,330 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 27 |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| City | Paris |

| Venue | Jardins des Champs-Élysées |

| Coordinates | 48°52′0″N 2°18′47″E / 48.86667°N 2.31306°E |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | 15 May 1855 |

| Closure | 15 November 1855 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Great Exhibition in London |

| Next | 1862 International Exhibition in London |

The Exposition Universelle of 1855 (French pronunciation: [ɛkspozisjɔ̃ ynivɛʁsɛl]), better known in English as the 1855 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, from 15 May to 15 November 1855. Its full official title was the Exposition Universelle des produits de l'Agriculture, de l'Industrie et des Beaux-Arts de Paris 1855.[1] It was the first of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937.[a] Nowadays, the exposition's sole physical remnant is the Théâtre du Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées, designed by architect Gabriel Davioud, which originally housed the Panorama National.

History

[edit]The exposition was a major event in France, then newly under the reign of Emperor Napoleon III.[2] It followed London's Great Exhibition of 1851 and attempted to surpass that fair's Crystal Palace with its own Palais de l'Industrie.

The arts displayed were shown in a separate pavilion on Avenue Montaigne.[3] There were works from artists from 29 countries, including French artists François Rude, Ingres, Delacroix[3] and Henri Lehmann,[4] and British artists William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.[3] However, Gustave Courbet, having had several of his paintings rejected, exhibited in a temporary Pavillon du Réalisme adjacent to the official show.

According to its official report, 5,162,330 visitors attended the exposition, of whom about 4.2 million entered the industrial exposition and 900,000 entered the Beaux Arts exposition.[1] Expenses amounted to upward of $5,000,000, while receipts were scarcely one-tenth of that amount. The exposition covered 16 hectares (40 acres) with 34 countries participating.[1]

For the exposition, Napoleon III requested a classification system for France's best Bordeaux wines which were to be on display for visitors from around the world. Brokers from the wine industry ranked the wines according to a château's reputation and trading price, which at that time was directly related to quality. The result was the important Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855.[5]

Influence on art

[edit]- The Rise of Realism: In the exposition, the French Realist painter Gustave Courbet had some of his works rejected by the official salon. He set his own pavilion called Pavilion of Realism, close to the main exhibition to display his work. Realism, which focused on portraying the everyday lives of common people with accuracy and without idealization, grew as a response to the academic and elite tendencies of art. By rebelling against the dominant trends, Courbet and his followers helped solidify Realism as a serious movement in the years that followed.[6]

- Promotion of Neoclassicism and Romanticism: Neoclassicism and Romanticism, the two dominant movements of the time was featured in the exposition. Key figures like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Neoclassicism) and Eugène Delacroix (Romanticism) presented their work, showcasing the stylistic debates of the time. This clash between Neoclassicism’s strict formality and Romanticism’s emotional intensity helped shape the public discourse on the purpose of art and laid the groundwork for future developments in artistic expression.[7]

- Introduction of Photography as an Art Form: Photography was also officially presented for the first time at the 1855 exposition. Its inclusion sparked discussions about its artistic potential and its relationship to painting. Photography’s role in capturing reality influenced artists, especially those in the Realist and Impressionist movements, who sought to depict the world with accuracy and immediacy.[8]

- Expansion of the Audience for Art: Before the exposition, the art world was largely limited to aristocratic circles and private academies, but the Exposition Universelle brought art to the masses, fostering a greater appreciation for different styles and making art more accessible.[9][10]

- International Artistic Dialogue: The 1855 exposition was one of the first global showcases of art, bringing artists from various countries together in a single venue. This allowed for the exchange of artistic ideas and techniques across borders. The cross-cultural interaction would influence artists' perspectives, expanding the scope of what art could represent.[11]

- Technological and Artistic Advancements: The exposition also featured innovations in art-making materials, such as the introduction of premixed oil paints in tubes, which allowed artists greater mobility and flexibility to work outdoors. This innovation became crucial for the later Impressionist painters like Édouard Manet and Claude Monet, who emphasized capturing natural light and the changing atmosphere.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ This includes six world expositions (in 1855, 1867, 1878, 1889, 1900 and 1937), two specialized expositions (in 1881 and 1925) and two colonial expositions (in 1907 and 1931).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Exposition Universelle. "1855, exposition universelle des produits de l'agriculture, de l'industrie et des beaux-arts". Exposition Universelle. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Art Nouveau. "L' Exposition Universelle de 1855 à Paris". L'art nouveau. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Ratcliffe, Barrie M. (2008). "Paris 1855". In Findling, John E.; Pelle, Kimberley D. (eds.). Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7864-3416-9.

- ^ Océanides grief of the foot of the rock where Prometheus was chained, Fitzwilliam Museum, 2014

- ^ Peppercorn, David (2003). Bordeaux. London: Mitchell Beazley. p. 83. ISBN 1-84000-927-6.

- ^ "Gustave Courbet | Biography, Paintings, Realism, A Burial at Ornans, The Stone Breakers, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ De Tholozany, Pauline. "Paris: Capital of the 19th Century". library.brown.edu. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Hannavy, John (2013-12-16). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-87327-1.

- ^ Stoklund, Bjarne (2024-10-24). "The Role of the International Exhibitions in the Construction of National Cultures in the 19th Century". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Gino Yazdinian, Nouriel. "19th Century Oil Paintings: Key Artists, Styles, and Techniques". NY Elizabeth. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Vignon, Claude (1855). Exposition universelle de 1855 beaux-arts (in French). Auguste Fontaine.

Further reading

[edit]- Elizabeth M. L. Gralton, 'Lust of the Eyes: The Anti-Modern Critique of Visual Culture at the Paris Expositions universelles, 1855–1900', French History & Civilization (2014), Vol. 5, pp 71–81.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.