Avro Manchester

| Manchester | |

|---|---|

Avro Manchester Mk.1A 'L7486' (note extended tail fins) | |

| General information | |

| Type | Heavy bomber |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Avro |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 202 |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1940–1941 |

| Introduction date | November 1940 |

| First flight | 25 July 1939 |

| Retired | 1942 |

| Developed into | Avro Lancaster |

The Avro 679 Manchester was a British twin-engine heavy bomber developed and manufactured by the Avro aircraft company in the United Kingdom. While not being built in great numbers, it was the forerunner of the more famed and more successful four-engined Avro Lancaster, which was one of the most capable strategic bombers of the Second World War.

Avro designed the Manchester in conformance with the requirements laid out by the British Air Ministry Specification P.13/36, which sought a capable medium bomber with which to equip the Royal Air Force (RAF) and to replace its inventory of twin-engine bombers, such as the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, Handley Page Hampden and Vickers Wellington. Performing its maiden flight on 25 July 1939, the Manchester entered squadron service in November 1940, just over twelve months after the outbreak of the war.

Operated by both RAF and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), the Manchester came to be regarded as a complete operational failure, primarily as a result of its Rolls-Royce Vulture engines, which were underdeveloped and hence underpowered and unreliable, and production was terminated in 1941. However, the Manchester was redesigned into a four-engined heavy bomber, powered by the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine instead, which became known as the Lancaster.

Development

[edit]The Manchester has its origins in a design produced by Avro in order to fulfil the British Air Ministry's Specification P.13/36. This was the same specification to which Handley Page had also produced their initial design for what would become the Halifax bomber.[1] Issued in May 1936, Specification P.13/36 called for a twin-engine monoplane "medium bomber" for "worldwide use", which was to be capable of carrying out shallow (30°) dive bombing attacks and carry heavy bombloads (8,000 lb/3,630 kg) or two 18 in (457 mm) torpedoes.[2][3] Additionally, provisions to conduct catapult assisted takeoffs, which would permit the carriage of the maximum payload, was also a stated requirement, although this provision was removed in July 1938.[4] The envisioned cruising speed of the bomber was to be a minimum of 275 mph at 15,000 feet.[5] The Air Ministry had expectations for an aircraft of similar weight to the B.1/35 specification, but smaller and faster.

Avro had already started work on a corresponding design prior to having received a formal invitation to tender. The company was in competition with Boulton Paul, Bristol, Fairey, Handley Page and Shorts. Vickers also had its Warwick, which had Napier Sabre engines, but eventually chose against tendering it. In early 1937, both the Avro design and the rival Handley Page HP.56 were accepted and prototypes of both ordered; but in mid-1937, the Air Ministry exercised their rights to order the types "off the drawing board". This skipping of the usual process was necessary due to the initiation of a wider expansion of the RAF in expectation of large scale war in Europe. From 1939, it was expected that the P.13/36 would begin replacing the RAF's existing medium bombers, such as the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, Handley Page Hampden and Vickers Wellington.

The Avro design used the Rolls-Royce Vulture 24-cylinder X-block engine, which was two Rolls-Royce Peregrine Vee cylinder blocks mounted one on top of the other, the bottom one inverted to give the "X" shape.[6] When developed in 1935, the Vulture engine had promise — it was rated at 1,760 hp (1,310 kW) but it proved woefully unreliable and had to be derated to 1,480–1,500 hp (1,100–1,120 kW). Avro's prototype Manchester L7246, was assembled by their experimental department at Manchester's Ringway Airport and first flew from there on 25 July 1939, with the second aircraft following on 26 May 1940.[2][7] The Vulture engine was chosen by Avro and not stipulated by the Air Ministry as is sometimes claimed;[a] other engine layouts considered included the use of two Bristol Hercules or Bristol Centaurus radial engines.[6] The Handley Page HP.56, always intended as the backup to the Avro, was redesigned to take four engines on the orders of the Air Ministry in 1937, when the Vulture was already showing problems.[11][b]

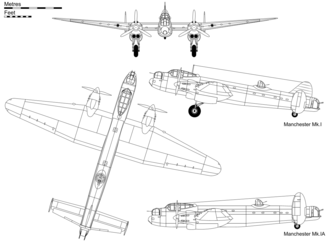

While the Manchester was designed with a twin tail, the first production aircraft, designated the Mk I, had a central fin added and twenty aircraft like this were built. They were succeeded by the Mk IA which reverted to the twin-fin system but used enlarged, taller fin and rudders mounted on a new tailplane, with span increased from 22 ft (6.71 m) to 33 ft (10.06 m). This configuration was carried over to the Lancaster, except for the first prototype, which also used a central fin and was a converted, unfinished Manchester.[12] Avro constructed 177 Manchesters while Metropolitan-Vickers completed 32 aircraft. Plans for Armstrong Whitworth and Fairey Aviation at Ringway (now Manchester Airport) to build the Manchester were abandoned. Fairey's order for 150 Manchesters was replaced by orders for the Halifax.

Design

[edit]

The Avro Manchester was designed with great consideration for ease of manufacture and repair.[13] The fuselage of the aircraft comprised longitudinal stringers or longerons throughout, over which an external skin of aluminium alloy was flush-riveted for a smooth external surface.[13] The wings were of a two-spar construction, the internal ribs being made of aluminium alloys; fuel was contained with several self-sealing fuel tanks within the wings.[14] The tail shared a similar construction to the wing, featuring a twin fin-and-rudder configuration that provided good vision for the dorsal gunner.[15]

The cockpit housed the pilot and fighting controller's position underneath the canopy, and these two crew members were provided with all-round vision. The navigator was seated aft of the fighting controller and the position included an astrodome for use of a sextant.[15] The bomb aimer's station was housed inside the aircraft's nose, beneath the forward turret and bomb aiming was conducted using optical sights housed in this compartment.[16] For crew comfort on lengthy missions, a rest area was situated just to the rear of the main cabin.[17]

The aircraft's undercarriage was entirely retractable via hydraulic systems, or in an emergency, a backup air system.[13] The doors to the bomb bay were also operated by these systems, an additional safety measure was installed to ensure that the bombs could not be dropped if the doors were shut.[16] The bombs were housed on bomb racks inside the internal bomb bay, and other armaments such as torpedoes could also be fitted.[16] All fuel tankage was located in the wings in order to keep the fuselage free to accommodate more armaments in the bomb bay which covered nearly two-thirds of the underside of the fuselage.[6]

Vulnerable parts of the aircraft were armoured; the pilot had additional armour and bulletproof glass and an armoured bulkhead was to the rear of the navigator's position.[15] The Manchester featured three hydraulically-operated turrets, located in the nose, rear and mid-upper fuselage;[12] the addition of a ventral turret directly behind the bomb bay had been considered and tested on the second prototype, but did not feature on production aircraft.[c][6] Access to all crew stations was provided by a walkway and crew positions had nearby escape hatches.[18]

The Manchester was powered by a pair of Vulture engines; in service these proved to be extremely unreliable. Aviation author Jon Lake stated of the Vulture: "The engine made the Manchester mainly notable for its unreliability, poor performance, and general inadequacy to the task at hand" and attributed the aircraft's poor service record to the engine troubles.[12]

I was one of the six original pilots to have flown with the first Manchester squadron. That was a disaster. The aircraft itself, the airframe, had many shortcomings in equipment in the beginning, but as we found out Avro were excellent in doing modifications and re-equipping the aeroplane. The engines never were and never did become reliable. They did not give enough power for the aeroplane, so we ended up with two extremely unreliable 1,750 hp engines having to haul a 50,000-pound aircraft. We should really have had 2,500 hp engines. You felt that if you'd lost one, that was it, you weren't coming home. It didn't matter if you feathered the propeller or not. There was only one way you went and that was down. I have seen an aircraft doing a run up on the ground and have two pistons come right out through the side of the engine. The original bearings were made without any silver as an economy measure, so they weren't hard enough. The bearings would collapse the connecting rod and the piston would fling out through the side of the engine and bang! Your engine just destroyed itself.[19][permanent dead link]

Operational history

[edit]

On 5 August 1940, the first production Avro Manchester, L7276, was delivered to RAF Boscombe Down in advance of service acceptance trials.[4] In November 1940, the Manchester officially entered service with the newly reformed No. 207 Squadron of RAF Bomber Command. The type passed all acceptance tests by 21 December 1940, and 207 Squadron had at least eight Manchesters on strength by the end of 1940.[20] The Manchester's first operational mission was conducted on 24–25 February 1941 in a raid on the French port of Brest.[21][22] On 13 March 1941, L7319 became the first Manchester to be shot down by enemy fire.[23]

On 13 April 1941, all Manchesters were temporarily grounded due to a higher than expected number of engine bearing failures; on 16 June 1941, a second grounding of the type was ordered due to more engine troubles.[24] The unserviceability of the Vulture engine forced squadrons to make use of obsolete bombers such as the Hampden in its place. Upon the restart of operations in August 1941, additional failings were encountered; excessive tail flutter, hydraulic failures and faulty propeller feathering controls.[25] Production of the Manchester was halted in November 1941, by which point a total of 202 aircraft had been constructed. A total of eight bomber squadrons were equipped with the type, it also served in two further squadrons and also saw use by RAF Coastal Command.[22]

While modifications were made by Avro to address some of the technical issues experienced, unit strength suffered and Bomber Command was frequently unable to raise significant numbers of aircraft to participate in large bombing missions; on 7 November 1941, all of the RAFs serviceable bombers had been dispatched to bomb Berlin, out of a force of over 400 bombers, only 15 were Manchesters.[26] On 3 March 1942, out of a force of nearly 200 bombers sent against a Renault factory near Paris, 25 were Manchesters;[27] while during the first 1,000 bomber raid on Cologne on 30 May 1942, 35 Manchesters were amongst the 1,047 bombers sent to attack the city.[28] Flying Officer Leslie Manser was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions while piloting Manchester L7301 of 50 Squadron during the Cologne bombing mission.[29]

The Mk III Manchester (serial number BT308) which first flew on 9 January 1941, was essentially the first Lancaster, featuring a longer wing fitted with four Rolls-Royce Merlins in new unitized, power-egg nacelles – originally developed by Rolls-Royce for the Merlin-powered Beaufighter II – although initially retaining the three fins and twin outboard rudders (the central fin had no movable control surface) of the Manchester I. BT308 received the "Lancaster" name immediately after its first flight. The second prototype Lancaster DG595 featured the twin, enlarged fins and rudders of the Manchester IA. Manchester production continued until November of that year but some aircraft that were still in production were instead completed as Lancasters.

The 193 operational Manchesters flew 1,269 sorties with Bomber Command, dropping 1,826 tons (1,657 tonnes) of bombs and lost 78 aircraft in action, flying its last operation against Bremen on 25 June 1942.[30][31] A further 45 were non-operational losses of which 30 involved engine failure. The Manchester was withdrawn from operations in mid-1942 in favour of more capable aircraft. Its final role in RAF service was as instructional trainers for converting crews to the RAF's new Lancaster bombers; the Manchester and Lancaster shared nearly identical crew positions and fuselages.[31] The type persisted in use for training purposes into 1943 before being completely retired.[12]

Variants

[edit]- Manchester L7246

- First prototype originally with twin tail. Due to lack of directional stability, it had a third fin added. Became a training airframe in November 1942.

- Manchester L7247

- Second prototype first flown 26 May 1940, fitted with armament, became a training airframe in October 1941.

- Manchester I

- First production version with 90 ft wing and 28 ft twin tail and additional central fin later added; 20 of this type were built.[d]

- Manchester IA

- Main production version with 90 ft wing, twin tail with 33 ft enlarged tailplane. It also had taller fins and rudders.

- Manchester IB

- As Manchester IA but with thin-gauge fuselage skin.

- Manchester IC

- As Manchester IB but with 2 x 2,520 hp Bristol Centaurus. Installed in one airframe but never flown.[e]

- Manchester II

- As Manchester IB but with 95 ft wing.

- Manchester IIA

- As Manchester II but with 2 x Bristol Centaurus. None built.

- Manchester III BT308

- This version was powered by four Merlin engines with increased wingspan; also, the three fins and rudders of the Manchester I were retained. This variant was the first prototype of the later Avro Lancaster.[f]

Orders and production

[edit]- Two prototypes were ordered against specification P.13/36 and were built by Avro at Ringway.

- Production contract for 200 Manchesters placed with Avro to be built at Chadderton, contract changed to Lancaster I production after 157 had been built, delivered between August 1940 and November 1941.

- Production contract for 150 Manchesters placed with Fairey to be built at Ringway, order cancelled.

- Production contract for 200 Manchesters placed with Metropolitan-Vickers at Trafford Park, contract changed to Lancaster I production after 43 had been built, delivered between March 1941 and March 1942. The first 12 aircraft being built on the Trafford Park production line were destroyed in a German air raid on 23 December 1940, not being completed they are not included in the total aircraft built.

- Production contract for 150 Manchesters placed with Armstrong-Whitworth, order cancelled.

In total two prototypes and 200 production aircraft were built before the production lines changed to building the four-engine Lancaster.

Operators

[edit]- Royal Australian Air Force

- No. 460 Squadron RAAF (August 1942 - October 1942) [32]

- Royal Air Force

- No. 49 Squadron RAF at RAF Scampton (April 1942 – June 1942)

- No. 50 Squadron RAF at RAF Skellingthorpe (April 1942 – June 1942)

- No. 61 Squadron RAF at RAF Hemswell (June 1941 – June 1942)

- No. 83 Squadron RAF at RAF Scampton (December 1941 – June 1942)

- No. 97 Squadron RAF at RAF Waddington then RAF Coningsby (February 1941 – February 1942)

- No. 106 Squadron RAF at RAF Coningsby (February 1942 – June 1942)

- No. 207 Squadron RAF at RAF Waddington then RAF Bottesford (November 1940 – March 1942)

- No. 25 Operation Training Unit at RAF Finningley

- No. 44 Conversion Flight

- No. 1485 Flight RAF

- No. 1654 Heavy Conversion Unit

- No. 1656 Heavy Conversion Unit

- No. 1660 Heavy Conversion Unit

- No. 1668 Heavy Conversion Unit

- Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment

- Torpedo Development Unit at RAF Gosport

Specifications (Manchester Mk I)

[edit]

Data from Aircraft of the Royal Air Force 1918–57,[22] Avro Aircraft since 1908,[30] Flight[13]

General characteristics

- Crew: 7

- Length: 70 ft (21 m)

- Wingspan: 90 ft 1 in (27.46 m)

- Height: 19 ft 6 in (5.94 m)

- Wing area: 1,131 sq ft (105.1 m2)

- Airfoil: root: NACA 23018; tip: NACA 23012[33]

- Empty weight: 31,200 lb (14,152 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 50,000 lb (22,680 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Vulture I X-24 liquid-cooled piston engine, 1,760 hp (1,310 kW) each

- Propellers: 3-bladed constant-speed feathering propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed: 265 mph (426 km/h, 230 kn) at 17,000 ft (5,200 m)

- Range: 1,200 mi (1,900 km, 1,000 nmi) with maximum bomb load of 10,350 lb (4,695 kg)

- Service ceiling: 19,200 ft (5,900 m)

Armament

- Guns: 8 × 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, (in Nash & Thompson nose (2), dorsal (2) and tail (4) turrets)

- Bombs: 10,350 lb (4,695 kg) bomb load

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Historian Francis K. Mason claimed that the engine selection was a part of the specification,[5] as does aviation author Chaz Bowyer,[8] Buttler states the Ministry specified prototypes with Hercules and Vulture engines,[9] and Sinnott refutes the assertion.[10]

- ^ Handley Page's aborted HP.56 proposal would become the four engine HP.57 that entered service as the Handley Page Halifax, a significantly more successful aircraft than the Manchester.

- ^ German pilots soon learnt of the lack of any defence in the ventral area on both the Manchester and its successor the Lancaster, and would often attack the aircraft in a manner to exploit this vulnerability.[6]

- ^ Designations are internal Avro ones circa November 1939, the Air Ministry only used the 'Mk I' and 'MK IA' designations to differentiate between the early triple-fin and later twin-fin variants.

- ^ Centaurus development had been halted to enable Bristol to concentrate effort on the Hercules.

- ^ The initial Avro proposal for 4 x Rolls-Royce Merlins was made September 1939. Alternative engine projects included 2 x 2,100 hp Napier Sabres, 2 x Bristol Hercules (layout only, 1940), 2 x Bristol Pegasus, layout only, 1940.[citation needed]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Lake 2002, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Lewis 1974, p. 299.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 25.

- ^ a b Bowyer 1974, p. 29.

- ^ a b Mason 1994, p. 323.

- ^ a b c d e Bowyer 1974, p. 26.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Buttler, 2004 p102-103

- ^ Sinnott 2001, pp. 165–171.

- ^ Lake 2002, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d Lake 2002, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Flight 1942, p. 555.

- ^ Flight 1942, pp. 555–556.

- ^ a b c Flight 1942, p. 556.

- ^ a b c Flight 1942, p. 557.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 28.

- ^ Flight 1942, pp. 556–557.

- ^ "Before the Lancs", Early Days, Personal Stories, The Bomber Command Association

- ^ Bowyer 1974, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Jackson 1990, p. 355.

- ^ a b c Thetford 1957

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 31.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 32.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 33.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 34.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 35.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, p. 38.

- ^ Bowyer 1974, pp. 38, 41.

- ^ a b Jackson 1990, p. 356.

- ^ a b Bowyer 1974, p. 43.

- ^ "ADF Serials - Avro Manchester".

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Avro Manchester – Details and Performance of Our Heaviest Twin-engined Bomber". Flight. 4 June 1942. pp. 555–557. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- Bowyer, Chaz. Aircraft Profile No. 260: Avro Manchester. Windsor, UK: Profile Publications, 1974.

- Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Fighters and Bombers 1935–1950. Hickley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-1-8578-0179-8.

- Jackson, A.J. Avro Aircraft since 1908. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, Second edition, 1990. ISBN 0-85177-834-8.

- Lake, Jon. The Great Book of Bombers: The World's Most Important Bombers from World War I to the Present Day. Zenith Imprint, 2002. ISBN 0-76031-347-4.

- Lewis, Peter. The British Bomber since 1914. London: Putnam, Second edition, 1974. ISBN 0-37010-040-9.

- "Manchesters". Aeromilitaria No. 2. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd., 1990.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Bomber since 1914. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1994. ISBN 0-85177-861-5.

- Sinnott, Colin. The RAF and Aircraft Design 1923–1939: Air Staff Operational Requirements (Studies in Air Power). London: Frank Cass, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7146-5158-3.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force 1918–57. London: Putnam, First edition, 1957. ISBN 0-37000-101-X.

Further reading

[edit]- Chant, Christopher. Lancaster: The History of Britain's Most Famous World War II Bomber. Bath, UK: Parragon, 2003. ISBN 0-75258-769-2.

- Holmes, Harry. Avro: The History of an Aircraft Company. Marlborough, UK: Crowood Press Ltd, Second edition, 2004. ISBN 1-86126-651-0.

- Holmes, Harry. Avro Lancaster (Combat Legend series). Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 2002. ISBN 1-84037-376-8.

- Jackson, Robert. Aircraft of World War II. Enderby, UK: Silverdale Books, 2006. ISBN 1-85605-751-8.

- Kirby, Robert. Avro Manchester: The Legend Behind the Manchester. Leicester, UK: Midland Publishing, 1995. ISBN 1-85780-028-1.

- Mackay, R.S.G. Lancaster in action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1982. ISBN 0-89747-130-X.