Codex Runicus

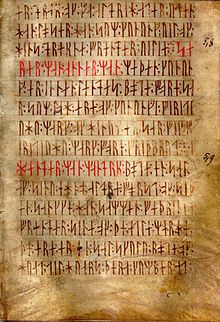

The Codex Runicus is a codex of 202 pages written in medieval runes around the year 1300 which includes the oldest preserved Nordic provincial law, Scanian Law (Skånske lov) pertaining to the Danish land Scania (Skåneland). Codex Runicus is one of the few runic texts found on parchment. The manuscript's initials are painted various colors and the rubrics are red. Each rune corresponds to a letter of the Latin alphabet.

The Codex Runicus has the shelfmark AM 28 8vo and is part of the Arnamagnæan Collection in the Arnamagnæan Institute at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.[1][2]

Runic manuscripts

[edit]

The Codex Runicus is considered by most scholars a nostalgic or revivalist use of runes and not a natural step from the Nordic runic script culture of the Viking Age to the medieval Latin manuscript culture.[3]

A similar use of runes in a Scandinavian manuscript from this era is known only from the small fragment SKB A 120, a religious text about Mary's lament at the cross. The two manuscripts are similar in how the runes are formed and also in their language use, and it has therefore been suggested that they were both written by the same Scanian scribe. Some scholars argue that they were written at the scriptorium at the Cistercian monastery at Herrevad in Scania, although the idea is contested.[4]

Some historians have considered it feasible that the Codex is a part and remainder of a formerly substantial collection of Scandinavian runic manuscripts, obliterated during the destruction of monasteries and libraries that followed the Protestant Reformation. Support for this idea has been found in reports written by Olaus Magnus, a Catholic ecclesiastic active during the 16th century in Uppsala, Sweden, who fled the country due to the Reformation. According to Olaus Magnus, there were many books written with runes in important Swedish religious centres, such as Skara and Uppsala, before the Reformation.[5] Other historians have questioned the accuracy of his report.[5]

Content of the Codex

[edit]

The manuscript has three major parts: the Scanian Law (fol. 1-82), the Scanian Ecclesiastical Law (fol. 84–91), a chronicle of the early Danish monarchs (fol. 92-97) and a description of the Danish-Swedish border (fol. 97-100). The Scanian Ecclesiastical Law (Skånske Kirkelov) is a settlement detailing the administration of justice agreed upon by the Scanians and the archbishop of Lund in the late 12th century.[6] The two law texts are written in the same hand, but the non-legal material of the codex, beginning on leaf 92, is believed to have been added in another hand, at a later date.[7] The history section consists of a fragment of a list of Danish kings and a chronicle beginning with the legendary Danish king Hadding's son Frode and ending with Eric VI of Denmark. Following the historical texts is a description of the oldest border between Sweden and Denmark (referred to as "the Daneholm settlement"). On the last leaf of Codex Runicus is a verse with musical notations - the first musical notations written in Scandinavia[according to whom?]. It is the earliest written evidence of secular music in Denmark, a non-rhythmic notation on a four-line staff.[8]

Transliteration

[edit]

Like other Scandinavian manifestations of Medieval runes, the runic alphabet of the Codex Runicus contains a sign for each phoneme of the language. A dotted variant had been introduced in order to separate voiceless k from the corresponding voiced consonant g. New runes introduced for the vowel sounds also appear in the codex.

The text on leaf 27r, from the first rubric (line 3), reads:

- Særær man annær man mæþæn kunung ær innæn lændæs bøtæ fore sar sum loh æræ :ok kunungi firitiuhu mark ok hinum ær sar fik firitiuhu mark fore friþbrut."

- (If a man wounds another man while the king is in the province he shall pay a fine for the wound in accordance with the law, and 40 marks to the king and 40 marks for breach of the peace to the one who was wounded.)[1]

The verse with the musical notations is the first two lines of the folk song Drømde mig en drøm i nat (I dreamt a dream last night), about a girl who dreams of becoming a rich woman. The melody is one that is well known to all Danes, having been used as an interval signal on Danish radio since 1931.

The section with the verse and musical notations are on the last leaf and reads:

- Drømde mik en drøm i nat (I dreamt a dream last night),

- um silki ok ærlik pæl (of silk and fine fur).

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b AM 28 8vo – Codex runicus Archived 1999-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. Scanned version of Codex Runicus. The Arnamagnæan Institute, a teaching and research institute within the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Copenhagen.

- ^ Det Arnamagnæanske Haandskrift No 28, 8vo: Codex Runicus. Kommissionen for det Arnamagnæanske Legat, København: 1877.

- ^ Frederiksen, Britta Olrik (2003). "The History of Old Nordic manuscripts IV: Old Danish". In Bandle, Oskar; et al. (eds.). The Nordic Languages: An International Handbook of the History of the North Germanic Languages. Vol. 1. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 819–823. ISBN 3-11-014876-5.

- ^ Frederiksen, Britta Olrik (2003). "The History of Old Nordic manuscripts IV: Old Danish", p. 821: "Something of a similar kind is known only in the small fragment SKB A 120, and given that it stands close to AM 28 8vo in terms of the form of the runes and the language (Scanian), it has been suggested that it the two manuscripts come from the same scriptorium; it has been further suggested, on rather meager grounds, that this scriptorium may have been at the Cistercian monastery at Herrevad in Scania."

- ^ a b Enoksen, Lars Magnar. (1998). Runor : historia, tydning, tolkning. Historiska Media, Falun. ISBN 91-88930-32-7 p. 175

- ^ Society for Danish Language and Literature. Kulturhistorisk baggrund (Cultural historic background). In Danish. Retrieved 20 February 2007

- ^ Kr. Kålund, Katalog, II, p. 344 Archived 1999-10-03 at the Wayback Machine. The Arnamagnæan Institute, Faculty of Humanities, University of Copenhagen. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ The Earliest Evidences of Musical Activities Archived 2005-12-30 at the Wayback Machine. Early Danish Music. Cultural Denmark. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. Retrieved 22 May 2007

Further reading

[edit]- Brøndum-Nielsen, Johannes; Svend Aakjær; D.J. Jørgensen (1933). Skånske lov, Danmarks gamle landskabslove, Bd. I. København. pp. 1–199.